You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueCan't wait for the update!

I may have been a little ambitious with my timetable for the next update, but I'm still hoping to get it out sometime today.It comes out today

Amen!Take your time, you’re the one doing this for free lol

Yah I just hope that this tl changes things enough to prevent the Armenian genocide

Easiest way to do that would be to butterfly the Young Turks and Turkish nationalism as we know it, although I have no idea how you could do that. Oddly enough, maybe the trick would be to have them stay in control over more of Ottoman Europe? Then imperial multiculturalism could beat out ethnic nationalism in the nation.

The military options—like Russia conquering their way into central Anatolia—don’t necessarily prevent some genocide because Armenians lived throughout the empire.

maybe if when the ottomans lose controls of the Balkans careened into the collapse of the empire giving a chance for an independent armenina ,Easiest way to do that would be to butterfly the Young Turks and Turkish nationalism as we know it, although I have no idea how you could do that. Oddly enough, maybe the trick would be to have them stay in control over more of Ottoman Europe? Then imperial multiculturalism could beat out ethnic nationalism in the nation.

The military options—like Russia conquering their way into central Anatolia—don’t necessarily prevent some genocide because Armenians lived throughout the empire.

maybe if when the ottomans lose controls of the Balkans careened into the collapse of the empire giving a chance for an independent armenina ,

That didn’t happen IOTL, and with good cause: Ottoman censuses from the era show the Armenians as a minority in every province they inhabited. There were no large, coherent Armenian regions to readily break away.

Granted, foreign interference—say, an invading Russian army causing an emigration of Turks like what happened in the Balkans—could change the picture on the ground.

Seems like the only hope they have in that case is consolidating under Russian rule if they get that far.That didn’t happen IOTL, and with good cause: Ottoman censuses from the era show the Armenians as a minority in every province they inhabited. There were no large, coherent Armenian regions to readily break away.

That didn’t happen IOTL, and with good cause: Ottoman censuses from the era show the Armenians as a minority in every province they inhabited. There were no large, coherent Armenian regions to readily break away.

Granted, foreign interference—say, an invading Russian army causing an emigration of Turks like what happened in the Balkans—could change the picture on the ground.

Isn’t there good reason to believe that ottoman census info is blatantly lying when it comes to the ethnic comoposition of their territory? I can’t remember exactly but I have the impression that basically all censuses by Balkan nations and the ottomans in the relevant time period were total bullshit designed to justify their land claims?

Isn’t there good reason to believe that ottoman census info is blatantly lying when it comes to the ethnic comoposition of their territory? I can’t remember exactly but I have the impression that basically all censuses by Balkan nations and the ottomans in the relevant time period were total bullshit designed to justify their land claims?

Yes, definitely, and there’s also the issue of “crypto-Armenians”—we know this because apparently there are still a number of them in Turkey today.

Still, though, Armenians being a minority (probably more than the officially stated ~10 percent, granted) in eastern Anatolia seems plausible. During this era Kars and modern Armenia were under the Russians, which would make sense as where most of the Armenians were.

Yes, definitely, and there’s also the issue of “crypto-Armenians”—we know this because apparently there are still a number of them in Turkey today.

Still, though, Armenians being a minority (probably more than the officially stated ~10 percent, granted) in eastern Anatolia seems plausible. During this era Kars and modern Armenia were under the Russians, which would make sense as where most of the Armenians were.

By 1912 there where roughly 1.9 million Armenians throughout Anatolia and Constantinople. They may not have been an absolute majority in the 6 vilayets but they certainly formed a very sizable minority, even the Ottoman census gives about 42% for Van and 32% for Bitlis being Armenian in 1893.

By 1912 there where roughly 1.9 million Armenians throughout Anatolia and Constantinople. They may not have been an absolute majority in the 6 vilayets but they certainly formed a very sizable minority, even the Ottoman census gives about 42% for Van and 32% for Bitlis being Armenian in 1893.

That makes more sense. The one I saw must have been extremely biased...

The Bosnian rebellion in this timeline is mostly modeled after the OTL Bosnian Uprising from 1831 to 1832. The length of the revolt was longer as they informally allied themselves with the Albanian Beys (who weren't all massacred ITTL at Monastir) resulting in a stronger and longer lasting Albanian rebellion as well. When the Ottomans finally regained control of both Bosnia and Albania, they initiated a more thorough purge of the Aghas, Ayans, and Beys of Albania and Bosnia, effectively depriving their people of a native leadership. This will have some effects later on.Netherlands for the win tbh

I wonder what the repercussions of the Bosnian rebellion are, seeing that Bosnia was plurality Serbian until, like, the 70's (20th century)

Well the Armenian Genocide is about 70 years away from now ITTL so a lot can and will happen between now and then. Things are already somewhat different in this timeline, Russia for instance gained Kars in addition to their OTL gains in the 1828-1829 Russo-Turkish War and the Ottoman Sultans have begun some of their reforms a little earlier which have both positive and negative effects on the Armenians and other religious minorities across the Empire.Yah I just hope that this tl changes things enough to prevent the Armenian genocide

Chapter 60: The Fire Spreads

Chapter 60: The Fire Spreads

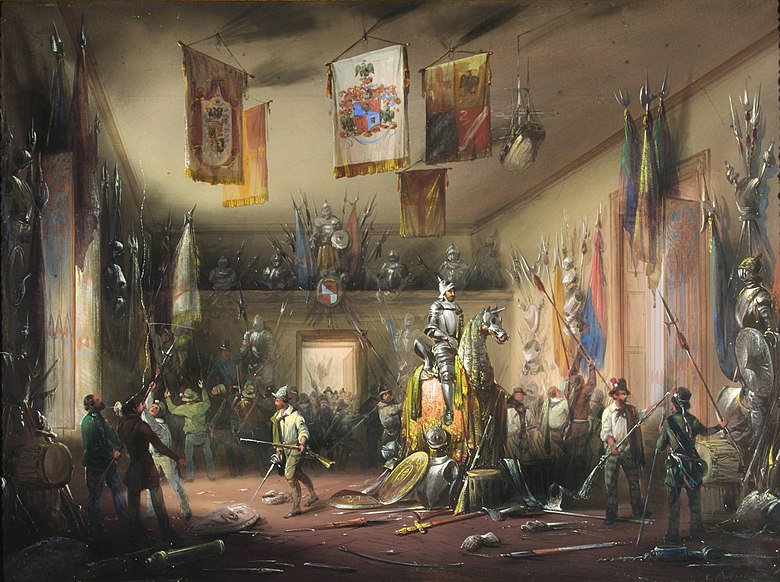

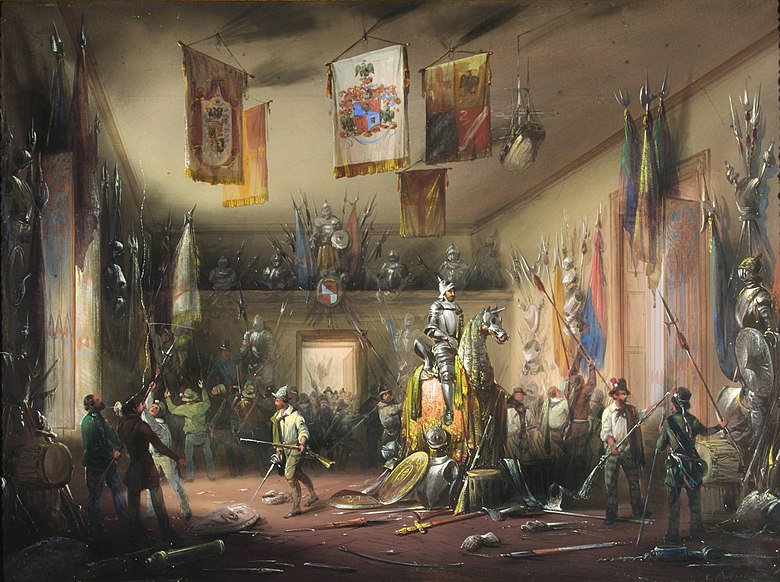

Scene from the Milanese Uprising of 1848

Although the war in Belgium was certainly the first major conflict to arise from the Revolutions of 1848, it was not the only major flashpoint of social unrest and political activism taking place across the European continent at this time. The deposition of King Otto had pried open the gates of liberalism and radicalism that had been barred shut since the end of the Napoleonic Wars and soon every state from Britain and France in the West to Austria and Russia in East would feel the fire of revolution. The German Confederation would be no different as revolutionary fervor soon took hold of various states across the region beginning with the small Grand Duchy of Baden. Located along the frontier with France, Baden had long been a hotbed of German liberalism since the Napoleonic Wars as feudalism and serfdom remained prominent features of Baden’s society. The people generally lived as peasants in relative squalor while the nobility enjoyed a life of leisure and luxury, leading to anger and hostility between the classes and enabling revolutionary ideals to take root in land. Over time these feelings would dissipate thanks to an improving Badische economy in the 1820’s and the persecution of liberals by the resurgent nobility, but they would never truly disappear.

The ascension of Grand Duke Leopold in 1830, would serve to reignite these lingering embers as he would prove to be a remarkably progressive ruler for his time. He appointed liberal ministers throughout his government and he lessened the restrictions on the press. He would end the persecution of political clubs and religious minorities earning him great praise from the people of Baden. Leopold would even engage in popular economic reforms and industrialization projects, meant to improve the livelihoods of his people, most of whom remained beholden to the land they toiled and tilled upon. And yet, for all his promises and accomplishments, Leopold would be reluctant to support more radical initiatives such as the complete abolishment of feudalism in Baden, the establishment of a written constitution, and the unification of Germany disappointing many liberals within Baden.

The famines of 1845, 1846, and 1847, along with the ensuing economic recessions of 1846 and 1847 would utterly devastate the Grand Duchy’s agricultural industry leaving tens of thousands unemployed and leading many thousands to fall into poverty. The region which had struggled with overpopulation for years now was ravaged with famine as entire families starved to death. Leopold’s industrialization initiatives would only worsen matters for the people of Baden as the Government’s already limited resources were funneled towards factories and mills, rather than food and simple sustenance. Angered at the callousness of the Badische elite and with nothing better to do, most of the unemployed began agitating for reform, protesting before their local municipal buildings or demonstrating outside the Badische Landtage in Karlsruhe. By the Summer of 1847, the Grand Duchy of Baden had all the warning signs of a revolution in the making. All it needed was a spark to ignite it and they needn’t wait long for that.

Emboldened by the overthrow of King Otto of Belgium in early September 1847, many of Baden’s leading liberals would flock to the important railroad junction of Offenburg on the 13th of September to air their grievances and make their demands for reformation known. In attendance were well over 700 leading liberals, radicals, revolutionaries, nationalists, and socialists from across Baden and the German Confederation, with the most prominent men in attendance being the firebrand democrats Gustav Struve, Valentin Streuber, and Friedrich Hecker. While some held differing opinions on the form of government they desired most, many if not all shared a common aspiration to establish a liberal constitution and a representative government in Baden. The Offenburg Assembly would take some time, but after several days of deliberation and debate, the assembly came to a consensus on their demands; the Offenburg Resolution.

The Offenburg Resolution

Firstly, they called for the writing of a constitution, establishing a representative form of government modeled after the United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Greece. Under the Offenburg Resolution, the Grand Duke would retain his status as the head of state, but his powers and privileges would be reduced from their present highs. The Badische Landtage would also be expanded into a bicameral legislature comprised of popularly elected representatives independent from the Grand Duke. The Resolution also called for the powers and influence of the Church, or more specifically the Jesuits, over the state’s bureaucracy to be curtailed significantly. They demanded the establishment of Jury Courts, based on the English Court of Sessions, enabling the accused to be tried before a jury of their peers. Finally, serfdom was to be abolished and all duties due to the nobility by the tenants on their lands were to be annulled.

Aside from these demands for political reform, the Offenburg Resolution included amendments to Baden’s economy, calling for yeomen farmers and small business owners to gain special privileges and protections against their larger competitors. They wanted tax rates and interest rates to be reduced from their present highs and that a progressive system of taxation be implemented in place of the current system which favored the nobility. The Badische military was also targeted for reform, with the Assembly demanding that the regular army be replaced with a national militia comprised of soldier citizens, loyal not to a sovereign, but to the constitution. They demanded that corporal punishment for both soldiers and civilians be ended upon humanitarian grounds, and they requested that practice of substitutions for military service be abolished. The final clause of the Offenburg Resolution called for the revocation of the Carlsbad Decrees which limited freedom of the press, the freedom of belief and conscious, the freedom of liberal professors to teach, the freedom to associate and assemble, and the freedom of German liberals to travel freely throughout the Confederation.

A meeting one month later by many of these same men in the town of Heppenheim would condense these many points into the Heppenheim Demands; the establishment of a Badische legislature, the abolition of feudalism and serfdom in Baden, the abolition of the army and its replacement with a citizens’ militia, the unrestricted freedom of the press, and the establishment of jury courts.[1] This condensed list of demands was then passed onto the Badische Landtage in Karlsruhe in late November 1847 where it would remain for several weeks much to the anger of the Badische liberals. The Diet was initially concerned over the radical demands of the resolution, but with popular demonstrations growing in size and increasing in violence by the day, they would be hard pressed to reject it. Ultimately, the people of Karlsruhe would make their decision for them, as a violent mob of 12,000 stormed the Landtage building on the 7th of December and successfully coerced the Diet into passing the Heppenheim Demands.

The successful enactment of the Heppenheim Demands in Baden would prompt other German Liberals across the German Confederation to begin pushing forward with their own assemblies and manifestos to varying degrees of success in the new year. Some rulers like King William I of Württemberg were compelled to appoint liberal ministers to their cabinets, while King Ernest Augustus of Hanover was forced to issue a new constitution that was slightly more liberal than the last. Other states like the Electorate of Hesse-Kassel and the Kingdom of Saxony would abolish serfdom, the system of substitution, and the exemption of the wealthy and well to do from military service. Some monarchs like King Ludwig of Bavaria and Grand Duke Louis II of Hesse and by Rhine would even be forced to abdicate in favor of their heirs due to strong public pressure against them. Yet amidst this cascade of liberalism spreading across Germany in 1848, Austria would prove much less conciliatory.

The Assembly of Eberfeld

The Austrian Empire had long been the bulwark of conservatism and absolutism in Central Europe, yet it too would experience its share of social unrest and political activism in 1848. As it was a multiethnic empire of Germans and Magyars, Czechs, and Croats, Poles and Transylvanians, Slovaks and Slovenes, stretching from the Alps in the West to the Carpathians in the East, it was a diverse state of differing peoples and differing ideals. The Hapsburgs and their Chancellor, Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich had long opposed the democratization and decentralization of the Empire, going to great lengths to oppress nationalists and revolutionaries through whatever means necessary. The Empire had survived the 1830 Revolutions relatively unscathed, with the only major uprising taking place in the Italian Peninsula. Many of the would-be revolutionaries were imprisoned and some 120 to 200 ring leaders would executed for treason and sedition in the immediate aftermath of the conflict, providing Metternich and the Hapsburgs with the appearance of a grand victory over their opponents.

However, beneath this façade of strength existed a rotting edifice ripe for change. The persecution and execution of the Carbonari leadership would only succeed in making them martyrs, strengthening the cause of Italian independence. Metternich’s harsh reprisals against similar groups in Bohemia, Galicia, and Hungary would also elicit great hatred among the nobility and commoners for the man and the Austrian government which he served. Nevertheless, the Austrian Chancellor had been awarded a great deal of leeway by Emperor Francis II thanks to his successful handling of the Italian Uprising and for his stalwart defense of the realm. But, by the start of 1848 Metternich was no longer the in insurmountable leader that he had once been as age and exhaustion had made him a sunken shadow of his former self. Mistakes in his once formidable judgement were becoming commonplace, with caution and patience being replaced with hubris and vanity, which would play out disastrously in his botched handling of the 1848 Revolutions.

The tide of revolution would sweep into Vienna in early March 1848 where it immediately took root among the intellectual class and the downtrodden. It would also inspire numerous students from the University of Vienna to begin writing pamphlets expressing liberal ideals that were soon spread across the city. Calls soon emerged demanding Metternich’s resignation and called on the Emperor to replace him, even many of his peers within the Austrian Government called for his removal from power. Despite this opposition, Metternich refused to resign unless explicitly ordered to do so by the Emperor and would stubbornly remain in power thanks to the support of a few key allies, albeit just barely.[2] With his power intact, Metternich ordered soldiers onto the streets to restore order to the city and for a time the unrest in Vienna would come to an end. While Metternich had succeeded in temporarily quieting Vienna, tensions would soon begin to boil over into armed conflict in other regions of the Empire.

Metternich’s retention of power would not serve him well in the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia where dissidents and nationalists rallied against him on a daily basis. An armed uprising had been narrowly avoided back in January when several demonstrators were killed by Austrian soldiers, leading Field Marshal Radetsky to imprison the offending soldiers and restrict the rest of his men to their barracks. The old Field marshal went to great lengths to keep the peace between the people and the soldiers, but his orders from above put him at a great disadvantage. While these measures certainly ingratiated Radetsky to the Milanese, his superiors in Vienna disapproved of his actions and ordered him to return his men to the streets.

Field Marshal Joseph Radetsky von Radetz, Commander of the Austrian Army in the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia

Sure enough, the return of Austrian soldiers to the streets of Milan would only inflame the situation as dissidents began protesting once again throughout the city. On the 25th of March, a band of radical republicans converged on the Governor’s palace at the Piazza della Scalla. As they progressed through the city their ranks swelled from what had initially been a small crowd in the hundreds to nearly 8,000 people, some of whom were armed. When the congregation reached the Piazza della Scala around noon they immediately pushed their way through the guards, killing three in the process. Once inside the rebels quickly confronted the acting Governor of Lombardy-Venetia, Maximilian Karl Lamoral O’Doneell demanding the freedom of the press, the creation of a national guard, and the establishment of a legislature.

Under duress, O’Donnell accepted the demands to the glee of the mob who promptly dispatched messengers to relay the news throughout the city. At this time Field Marshal Radetsky and his soldiers began investing the city hall, sparking a fierce melee between the Milanese and the Austrians. The battle in the Piazza della Scala would carry on for several hours, but by nightfall the city center was fully secured. Now freed, O’Donnell immediately renounced his earlier acceptance of the dissidents’ demands, but by this time it was too late as word had spread across the city of fighting between soldiers and civilians sparking a general uprising across the city. By dawn the next day, hundreds of barricades had been erected and tens of thousands of armed and angry Milanese defiantly stood atop them, effectively daring the Austrians to attack.

Radetsky’s troubles would only worsen in the days ahead as Metternich’s close ally Karl Ludwig, Count of Ficquelmont arrived in the city on the 28th of March to take control of the situation.[3] Ficquelmont had briefly served as Chancellor of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia the year prior to disastrous results as he thoroughly disenfranchised the local Milanese with his oppressive administration. Upon his arrival in Milan, Ficquelmont immediately ordered Radetsky to hold the city until reinforcements from Austria could arrive. For Radetsky this was an impossibility as his force of 60,000 was dispersed across the entire Po valley, of which only 12,000 were in Milan. In fact, Radetsky had been preparing to evacuate the city prior to Ficquelmont’s arrival on the scene, a premise which Ficquelmont found distasteful and reprehensible. Despite their disagreement Ficquelmont's authority was unquestionable as he was a stalwart ally of Chancellor Metternich, and so Radetsky was forced to comply.

Karl Ludwig (Born Charles Louis), Count of Ficquelmont

Soon word would reach Radetsky and Ficquelmont of additional revolts breaking out across Lombardy prompting nearly half of the Italian units in Austrian service to desert or defect en masse to the revolutionaries. Despite this worsening situation, Radetsky’s men still maintained control over much of the city center and the old Spanish walls providing some semblance of safety to the beleaguered Austrians. However, their situation was rapidly deteriorating as the Milanese would capture the Porta Lodovica on the 31st of March and the Porta Genova the following day, forcing a general withdrawal behind the old Medieval walls. Supply shortages were fast becoming an issue for the Austrians as they were effectively cut off from the outside world, leading to strict rationing of food and water as well as musket balls and powder. The worst news would come on the 3rd of April as preliminary reports indicated that the Sardinian Army had crossed the border into Lombardy-Venetia and were making for Milan at a rapid pace. While it was unclear which side they were on exactly, skirmishing had taken place along the border near Vigevano and Pavia indicating that the Sardinians were on the side of the revolutionaries.

With the situation rapidly deteriorating, Radetsky ordered his men to make a desperate breakout attempt towards the East over the objection of Ficquelmont and the Austrian Government. After several painstaking hours of fierce hand to hand fighting, the battered and bruised Austrian army would successfully escape Milan, but at a ghastly cost. Of the 16,000 Austrian soldiers who had been stationed in Milan or arrived as reinforcements in the days following the initial uprising, over half would be captured, killed, or wounded during the endeavor. More damaging however, was the removal of Radetsky from his command as Ficquelmont blamed the old Field Marshal for losing Milan and much of Lombardy to the Italian Revolutionaries.

The events in Lombardy were not the only source of conflict and revolution on the Italian Peninsula as the Papal States, the Duchies of Tuscany, Parma, and Lucca, the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont, and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies experienced their own extensive revolutions. The origin of this unrest dates back to the election of Pope Pius IX to the Papacy in May 1846 as he would begin a flurry of progressive reforms implemented throughout the Papal States during his tenure as the Bishop of Rome. He would pardon political prisoners and common criminals. He would appoint liberal ministers to influential posts and laymen to the bureaucracy. Finally, he would establish a municipal council for the governance of the city of Rome by its people. Most importantly, he was somewhat antagonistic towards the Austrian government for its heavy-handed punishment of Italian revolutionaries and nationalists, as well as the illegal occupation of Ravenna and Ferrara that took place in 1838.

However, these developments were unfortunately misinterpreted by many Italian liberals and nationalists who flocked to the Papal States in the vain hope that Pope Pius would bring about the independence of a united Italy. While the Pope was certainly sympathetic to the plight of the Italians and supported their desire for constitutionalism, he was not a nationalist, nor was he was a revolutionary. Nevertheless, Pius’ actions would inspire Italian nationalists and revolutionaries in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to rise in revolt against the tyrannical Bourbon monarchy on the 12th of January 1848. The Sicilians of Palermo would quickly drive the Bourbon soldiers from the city, before declaring the restoration of the earlier 1812 Constitution establishing a Sicilian Parliament, as well as the deposition of King Ferdinand II. The Sicilian Revolutionaries would soon thereafter claim the rest of the island, baring Messina, effectively splitting the Kingdom of Two Sicilies in two, Sicily which was held by the Revolutionaries, and Naples which was maintained by the Bourbons.

The People of Palermo rise up in revolt against the Bourbon Monarchy

Attempts to carry the revolution over to the mainland in Naples would generally meet with little success, as the Bourbons maintained naval supremacy near the straights of Messina. Nevertheless, some Nationalists would manage to make their way to Taranto and Bari where they attempted to raise the flag of revolt as well. While their efforts would meet with some initial success, they were steadily beaten back by government troops causing Bari and then Taranto to fall to the Bourbons in quick succession, leading many to flee in any direction that they could. Some would make their way back to Sicily where they would join in the fate of the revolution there, others would travel north to join the Lombards and Venetians in their fight against the Austrians, some would even attempt to cross the Adriatic Sea to the Balkans bringing their liberal ideals and nationalistic fervor with them.

The Kingdom of Greece was generally quite during the opening months of 1848 as economic stagnation and crop failures were comprised the worst concerns of the Greek Government. There was some unrest in April as students from the University of Athens advocated for various economic and social reforms, but nothing notable came of them aside from the lowering of the poll tax from 10 Drachma to 5 and the abolishment of all remaining restrictions on the press that had been holdovers from the Kapodistrias and Metaxas years. The Ottoman Empire was also relatively stable during this time aside from some provincial disputes and murmurs of nationalistic discontent. The Ottoman Empire’s vassals, the Danubian Principalities and the Principality of Serbia, were quite active as nationalists and liberals began advocating for greater autonomy and the liberation of their people from foreign oppression with increasing tenacity. By far though, the most active community in the Balkans during the opening months of the 1848 Revolutions were the Eptanesians of the Ionian Islands.

The Eptanesians were especially susceptible to the nationalistic and liberal messaging of the Neapolitan revolutionaries. For generations, the Ionian Islands had been under the suzerainty of the Serene Republic of Venice, only to fall under the sway of first the French then the Russians and Ottomans, before returning briefly to French rule, only to then fall under the protection of the British after the Napoleonic Wars. Established as the United States of the Ionian Islands, the Eptanesians were a de facto vassal of the British Empire, providing the Royal Navy with warm water ports in the Eastern Mediterranean all year long in return for a sizeable degree of autonomy in their internal affairs. This situation was generally amenable to the Eptanesians initially as they enjoyed some degree of local autonomy compared to their countrymen on the mainland. However, over time the British would erode the freedom of the Eptanesians, effectively reducing them to a British Colony in all but name. They deployed British soldiers on their islands and patrolled their coastlines with British ships, they controlled Eptanesian foreign and domestic policy, and they governed the islands with British administrators appointed not from Corfu, but from London.

This British occupation would unfortunately worsen following the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821. Using their wealth and resources, the Eptanesians would provide invaluable support to the Greek Revolutionaries during the Greek War of Independence, with some of the great leaders of the war emerging from the Islands like the remarkable Strategos Panos Kolokotronis and the former Greek Prime Minister Andreas Metaxas. Numerous weapons, funds, and men were funneled through the islands, much to the aggravation of the British Government which remained decidedly neutral, if not somewhat hostile towards the Greeks during the first years of the conflict. Several ships laden with provisions for the Greek Revolutionaries were unfortunately confiscated by the British authorities over the course of the war, leading to a building resentment between the British and the Eptanesians that would only worsen after the war’s end.

Although it would be slow at first, a movement clamoring for enosis, union with Greece began to emerge on the island after the end of the war in 1830. Demonstrations calling for union with Greece were a common occurrence in the various cities of the Ionian Islands, and measures calling for union with Greece would occasionally find their way to the Ionian Parliament, where they were swiftly voted down by the British dominated legislature. This situation would change in late October 1847, as the many disunited groups clamoring for union with Greece would coalesce to form the Kómma ton Rizospastón (the Party of Radicals), which campaigned on the promise of union with Greece. The Party of Radicals would prove to be a significant thorn in the side of the British Governor of the Ionian Islands, Lord High Commisioner John Colborne, 1st Baron Seaton.

The Party of Radicals (Kómma ton Rizospastón)

They organized protests against the continued British rule on the island and they purposefully boycotted British goods in favor of local Eptanesian products or Hellenic imports. The Party’s popularity among the people would earn them several seats within the Ionian Parliament where they began pushing their measures for enosis with greater effectiveness. These efforts were strongly opposed by the British Authorities on the islands who promptly arrested and imprisoned various Eptanesian MPs and unionists on the islands for seditious activity and treason against the Crown prompting mass unrest and riots across the islands. The arrival of several Neapolitan revolutionaries from Bari in late April 1848 would only serve to further destabilize the British’s hold on the islands as protests calling for union with Greece only intensified in the wake of the MP’s arrests.

Under orders from London to keep the peace on the islands, Baron Seaton declared martial law over the Ionian Islands and instated a curfew in Kerkyra (Corfu city). He forcibly closed various Radical newspapers, and he would even deport prominent Unionists from the islands. When these acts proved insufficient in ending the demonstrations, Seaton ordered the hanging of a handful of violent offenders for their behavior as a warning against further unrest. These acts by the British, would only worsen the demonstrations against them, leading to a gradual collapse in British rule on the islands. The British actions would also bring about stern condemnation from the Greek Government which issued a diplomatic complaint.

The events on the Ionian Islands were of little consequence to the British Government however. While the unrest was certainly unfortunate and unwanted, their focus was directed elsewhere, namely across the Channel in the lands of the now defunct Kingdom of Belgium and across the narrow sea in Ireland where famine and discontent reigned supreme. There was also the matter of Persia, which had defied British demands to vacate Afghanistan, necessitating a response by Parliament. War with the Persian Shah was undesirable, but it now seemed unavoidable given his recalcitrance and his continued propagation of war in the region. More worrying were reports of Russian aggression in Central Asia, as they had established forts along the Syr river and were fielding steamships in the Aral Sea.

The British were also embroiled in their own problems as the Charterists boldly made their move in mid-April. According to reports, some 150,000 men, women, and children had attended the Charterist assembly at Kennington Commons on the 12th, in a show of force meant to press the British Parliament into accepting their petition for reform. The Government in response assembled nearly 100,000 policemen, soldiers, and constables to maintain the peace and prevent any acts of aggression by the crowd. The Charterists were generally peaceful and the event came and went without much concern, nevertheless it provided quite the scare for the British government. With their attention diverted elsewhere, it came as no surprise that the events on the Ionian Islands were given little attention by the British Government, effectively leaving the matter for another time.

Next Time: Prussian Blues

[1] Based on the Four Pressing Demands by Gustave Struve.

[2] Metternich is in slightly better standing ITTL thanks to the lesser scale of the Belgian Revolution compared to the French Revolution of OTL. While there are still calls for his resignation, they are fewer and farer between enabling him to just barely remain in power for now. But he will soon wish he hadn’t.

[3] Karl Ludwig, Count of Ficquelmont was a prominent supporter of Metternich and had been appointed as chancellor of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia in 1847 to improve the Empire’s standing in the region. However, with the start of the Revolutions of 1848, he was recalled to Vienna and took part in the government following Metternich’s resignation until he too was forced to resign due to his association with Metternich. As Metternich has remained in power ITTL, Ficquelmont was sent back to Lombardy-Venetia to resume his earlier work of shoring up Austrian interests there.

Scene from the Milanese Uprising of 1848

Although the war in Belgium was certainly the first major conflict to arise from the Revolutions of 1848, it was not the only major flashpoint of social unrest and political activism taking place across the European continent at this time. The deposition of King Otto had pried open the gates of liberalism and radicalism that had been barred shut since the end of the Napoleonic Wars and soon every state from Britain and France in the West to Austria and Russia in East would feel the fire of revolution. The German Confederation would be no different as revolutionary fervor soon took hold of various states across the region beginning with the small Grand Duchy of Baden. Located along the frontier with France, Baden had long been a hotbed of German liberalism since the Napoleonic Wars as feudalism and serfdom remained prominent features of Baden’s society. The people generally lived as peasants in relative squalor while the nobility enjoyed a life of leisure and luxury, leading to anger and hostility between the classes and enabling revolutionary ideals to take root in land. Over time these feelings would dissipate thanks to an improving Badische economy in the 1820’s and the persecution of liberals by the resurgent nobility, but they would never truly disappear.

The ascension of Grand Duke Leopold in 1830, would serve to reignite these lingering embers as he would prove to be a remarkably progressive ruler for his time. He appointed liberal ministers throughout his government and he lessened the restrictions on the press. He would end the persecution of political clubs and religious minorities earning him great praise from the people of Baden. Leopold would even engage in popular economic reforms and industrialization projects, meant to improve the livelihoods of his people, most of whom remained beholden to the land they toiled and tilled upon. And yet, for all his promises and accomplishments, Leopold would be reluctant to support more radical initiatives such as the complete abolishment of feudalism in Baden, the establishment of a written constitution, and the unification of Germany disappointing many liberals within Baden.

The famines of 1845, 1846, and 1847, along with the ensuing economic recessions of 1846 and 1847 would utterly devastate the Grand Duchy’s agricultural industry leaving tens of thousands unemployed and leading many thousands to fall into poverty. The region which had struggled with overpopulation for years now was ravaged with famine as entire families starved to death. Leopold’s industrialization initiatives would only worsen matters for the people of Baden as the Government’s already limited resources were funneled towards factories and mills, rather than food and simple sustenance. Angered at the callousness of the Badische elite and with nothing better to do, most of the unemployed began agitating for reform, protesting before their local municipal buildings or demonstrating outside the Badische Landtage in Karlsruhe. By the Summer of 1847, the Grand Duchy of Baden had all the warning signs of a revolution in the making. All it needed was a spark to ignite it and they needn’t wait long for that.

Emboldened by the overthrow of King Otto of Belgium in early September 1847, many of Baden’s leading liberals would flock to the important railroad junction of Offenburg on the 13th of September to air their grievances and make their demands for reformation known. In attendance were well over 700 leading liberals, radicals, revolutionaries, nationalists, and socialists from across Baden and the German Confederation, with the most prominent men in attendance being the firebrand democrats Gustav Struve, Valentin Streuber, and Friedrich Hecker. While some held differing opinions on the form of government they desired most, many if not all shared a common aspiration to establish a liberal constitution and a representative government in Baden. The Offenburg Assembly would take some time, but after several days of deliberation and debate, the assembly came to a consensus on their demands; the Offenburg Resolution.

The Offenburg Resolution

Firstly, they called for the writing of a constitution, establishing a representative form of government modeled after the United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Greece. Under the Offenburg Resolution, the Grand Duke would retain his status as the head of state, but his powers and privileges would be reduced from their present highs. The Badische Landtage would also be expanded into a bicameral legislature comprised of popularly elected representatives independent from the Grand Duke. The Resolution also called for the powers and influence of the Church, or more specifically the Jesuits, over the state’s bureaucracy to be curtailed significantly. They demanded the establishment of Jury Courts, based on the English Court of Sessions, enabling the accused to be tried before a jury of their peers. Finally, serfdom was to be abolished and all duties due to the nobility by the tenants on their lands were to be annulled.

Aside from these demands for political reform, the Offenburg Resolution included amendments to Baden’s economy, calling for yeomen farmers and small business owners to gain special privileges and protections against their larger competitors. They wanted tax rates and interest rates to be reduced from their present highs and that a progressive system of taxation be implemented in place of the current system which favored the nobility. The Badische military was also targeted for reform, with the Assembly demanding that the regular army be replaced with a national militia comprised of soldier citizens, loyal not to a sovereign, but to the constitution. They demanded that corporal punishment for both soldiers and civilians be ended upon humanitarian grounds, and they requested that practice of substitutions for military service be abolished. The final clause of the Offenburg Resolution called for the revocation of the Carlsbad Decrees which limited freedom of the press, the freedom of belief and conscious, the freedom of liberal professors to teach, the freedom to associate and assemble, and the freedom of German liberals to travel freely throughout the Confederation.

A meeting one month later by many of these same men in the town of Heppenheim would condense these many points into the Heppenheim Demands; the establishment of a Badische legislature, the abolition of feudalism and serfdom in Baden, the abolition of the army and its replacement with a citizens’ militia, the unrestricted freedom of the press, and the establishment of jury courts.[1] This condensed list of demands was then passed onto the Badische Landtage in Karlsruhe in late November 1847 where it would remain for several weeks much to the anger of the Badische liberals. The Diet was initially concerned over the radical demands of the resolution, but with popular demonstrations growing in size and increasing in violence by the day, they would be hard pressed to reject it. Ultimately, the people of Karlsruhe would make their decision for them, as a violent mob of 12,000 stormed the Landtage building on the 7th of December and successfully coerced the Diet into passing the Heppenheim Demands.

The successful enactment of the Heppenheim Demands in Baden would prompt other German Liberals across the German Confederation to begin pushing forward with their own assemblies and manifestos to varying degrees of success in the new year. Some rulers like King William I of Württemberg were compelled to appoint liberal ministers to their cabinets, while King Ernest Augustus of Hanover was forced to issue a new constitution that was slightly more liberal than the last. Other states like the Electorate of Hesse-Kassel and the Kingdom of Saxony would abolish serfdom, the system of substitution, and the exemption of the wealthy and well to do from military service. Some monarchs like King Ludwig of Bavaria and Grand Duke Louis II of Hesse and by Rhine would even be forced to abdicate in favor of their heirs due to strong public pressure against them. Yet amidst this cascade of liberalism spreading across Germany in 1848, Austria would prove much less conciliatory.

The Assembly of Eberfeld

The Austrian Empire had long been the bulwark of conservatism and absolutism in Central Europe, yet it too would experience its share of social unrest and political activism in 1848. As it was a multiethnic empire of Germans and Magyars, Czechs, and Croats, Poles and Transylvanians, Slovaks and Slovenes, stretching from the Alps in the West to the Carpathians in the East, it was a diverse state of differing peoples and differing ideals. The Hapsburgs and their Chancellor, Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich had long opposed the democratization and decentralization of the Empire, going to great lengths to oppress nationalists and revolutionaries through whatever means necessary. The Empire had survived the 1830 Revolutions relatively unscathed, with the only major uprising taking place in the Italian Peninsula. Many of the would-be revolutionaries were imprisoned and some 120 to 200 ring leaders would executed for treason and sedition in the immediate aftermath of the conflict, providing Metternich and the Hapsburgs with the appearance of a grand victory over their opponents.

However, beneath this façade of strength existed a rotting edifice ripe for change. The persecution and execution of the Carbonari leadership would only succeed in making them martyrs, strengthening the cause of Italian independence. Metternich’s harsh reprisals against similar groups in Bohemia, Galicia, and Hungary would also elicit great hatred among the nobility and commoners for the man and the Austrian government which he served. Nevertheless, the Austrian Chancellor had been awarded a great deal of leeway by Emperor Francis II thanks to his successful handling of the Italian Uprising and for his stalwart defense of the realm. But, by the start of 1848 Metternich was no longer the in insurmountable leader that he had once been as age and exhaustion had made him a sunken shadow of his former self. Mistakes in his once formidable judgement were becoming commonplace, with caution and patience being replaced with hubris and vanity, which would play out disastrously in his botched handling of the 1848 Revolutions.

The tide of revolution would sweep into Vienna in early March 1848 where it immediately took root among the intellectual class and the downtrodden. It would also inspire numerous students from the University of Vienna to begin writing pamphlets expressing liberal ideals that were soon spread across the city. Calls soon emerged demanding Metternich’s resignation and called on the Emperor to replace him, even many of his peers within the Austrian Government called for his removal from power. Despite this opposition, Metternich refused to resign unless explicitly ordered to do so by the Emperor and would stubbornly remain in power thanks to the support of a few key allies, albeit just barely.[2] With his power intact, Metternich ordered soldiers onto the streets to restore order to the city and for a time the unrest in Vienna would come to an end. While Metternich had succeeded in temporarily quieting Vienna, tensions would soon begin to boil over into armed conflict in other regions of the Empire.

Metternich’s retention of power would not serve him well in the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia where dissidents and nationalists rallied against him on a daily basis. An armed uprising had been narrowly avoided back in January when several demonstrators were killed by Austrian soldiers, leading Field Marshal Radetsky to imprison the offending soldiers and restrict the rest of his men to their barracks. The old Field marshal went to great lengths to keep the peace between the people and the soldiers, but his orders from above put him at a great disadvantage. While these measures certainly ingratiated Radetsky to the Milanese, his superiors in Vienna disapproved of his actions and ordered him to return his men to the streets.

Field Marshal Joseph Radetsky von Radetz, Commander of the Austrian Army in the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia

Sure enough, the return of Austrian soldiers to the streets of Milan would only inflame the situation as dissidents began protesting once again throughout the city. On the 25th of March, a band of radical republicans converged on the Governor’s palace at the Piazza della Scalla. As they progressed through the city their ranks swelled from what had initially been a small crowd in the hundreds to nearly 8,000 people, some of whom were armed. When the congregation reached the Piazza della Scala around noon they immediately pushed their way through the guards, killing three in the process. Once inside the rebels quickly confronted the acting Governor of Lombardy-Venetia, Maximilian Karl Lamoral O’Doneell demanding the freedom of the press, the creation of a national guard, and the establishment of a legislature.

Under duress, O’Donnell accepted the demands to the glee of the mob who promptly dispatched messengers to relay the news throughout the city. At this time Field Marshal Radetsky and his soldiers began investing the city hall, sparking a fierce melee between the Milanese and the Austrians. The battle in the Piazza della Scala would carry on for several hours, but by nightfall the city center was fully secured. Now freed, O’Donnell immediately renounced his earlier acceptance of the dissidents’ demands, but by this time it was too late as word had spread across the city of fighting between soldiers and civilians sparking a general uprising across the city. By dawn the next day, hundreds of barricades had been erected and tens of thousands of armed and angry Milanese defiantly stood atop them, effectively daring the Austrians to attack.

Radetsky’s troubles would only worsen in the days ahead as Metternich’s close ally Karl Ludwig, Count of Ficquelmont arrived in the city on the 28th of March to take control of the situation.[3] Ficquelmont had briefly served as Chancellor of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia the year prior to disastrous results as he thoroughly disenfranchised the local Milanese with his oppressive administration. Upon his arrival in Milan, Ficquelmont immediately ordered Radetsky to hold the city until reinforcements from Austria could arrive. For Radetsky this was an impossibility as his force of 60,000 was dispersed across the entire Po valley, of which only 12,000 were in Milan. In fact, Radetsky had been preparing to evacuate the city prior to Ficquelmont’s arrival on the scene, a premise which Ficquelmont found distasteful and reprehensible. Despite their disagreement Ficquelmont's authority was unquestionable as he was a stalwart ally of Chancellor Metternich, and so Radetsky was forced to comply.

Karl Ludwig (Born Charles Louis), Count of Ficquelmont

Soon word would reach Radetsky and Ficquelmont of additional revolts breaking out across Lombardy prompting nearly half of the Italian units in Austrian service to desert or defect en masse to the revolutionaries. Despite this worsening situation, Radetsky’s men still maintained control over much of the city center and the old Spanish walls providing some semblance of safety to the beleaguered Austrians. However, their situation was rapidly deteriorating as the Milanese would capture the Porta Lodovica on the 31st of March and the Porta Genova the following day, forcing a general withdrawal behind the old Medieval walls. Supply shortages were fast becoming an issue for the Austrians as they were effectively cut off from the outside world, leading to strict rationing of food and water as well as musket balls and powder. The worst news would come on the 3rd of April as preliminary reports indicated that the Sardinian Army had crossed the border into Lombardy-Venetia and were making for Milan at a rapid pace. While it was unclear which side they were on exactly, skirmishing had taken place along the border near Vigevano and Pavia indicating that the Sardinians were on the side of the revolutionaries.

With the situation rapidly deteriorating, Radetsky ordered his men to make a desperate breakout attempt towards the East over the objection of Ficquelmont and the Austrian Government. After several painstaking hours of fierce hand to hand fighting, the battered and bruised Austrian army would successfully escape Milan, but at a ghastly cost. Of the 16,000 Austrian soldiers who had been stationed in Milan or arrived as reinforcements in the days following the initial uprising, over half would be captured, killed, or wounded during the endeavor. More damaging however, was the removal of Radetsky from his command as Ficquelmont blamed the old Field Marshal for losing Milan and much of Lombardy to the Italian Revolutionaries.

The events in Lombardy were not the only source of conflict and revolution on the Italian Peninsula as the Papal States, the Duchies of Tuscany, Parma, and Lucca, the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont, and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies experienced their own extensive revolutions. The origin of this unrest dates back to the election of Pope Pius IX to the Papacy in May 1846 as he would begin a flurry of progressive reforms implemented throughout the Papal States during his tenure as the Bishop of Rome. He would pardon political prisoners and common criminals. He would appoint liberal ministers to influential posts and laymen to the bureaucracy. Finally, he would establish a municipal council for the governance of the city of Rome by its people. Most importantly, he was somewhat antagonistic towards the Austrian government for its heavy-handed punishment of Italian revolutionaries and nationalists, as well as the illegal occupation of Ravenna and Ferrara that took place in 1838.

However, these developments were unfortunately misinterpreted by many Italian liberals and nationalists who flocked to the Papal States in the vain hope that Pope Pius would bring about the independence of a united Italy. While the Pope was certainly sympathetic to the plight of the Italians and supported their desire for constitutionalism, he was not a nationalist, nor was he was a revolutionary. Nevertheless, Pius’ actions would inspire Italian nationalists and revolutionaries in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to rise in revolt against the tyrannical Bourbon monarchy on the 12th of January 1848. The Sicilians of Palermo would quickly drive the Bourbon soldiers from the city, before declaring the restoration of the earlier 1812 Constitution establishing a Sicilian Parliament, as well as the deposition of King Ferdinand II. The Sicilian Revolutionaries would soon thereafter claim the rest of the island, baring Messina, effectively splitting the Kingdom of Two Sicilies in two, Sicily which was held by the Revolutionaries, and Naples which was maintained by the Bourbons.

The People of Palermo rise up in revolt against the Bourbon Monarchy

Attempts to carry the revolution over to the mainland in Naples would generally meet with little success, as the Bourbons maintained naval supremacy near the straights of Messina. Nevertheless, some Nationalists would manage to make their way to Taranto and Bari where they attempted to raise the flag of revolt as well. While their efforts would meet with some initial success, they were steadily beaten back by government troops causing Bari and then Taranto to fall to the Bourbons in quick succession, leading many to flee in any direction that they could. Some would make their way back to Sicily where they would join in the fate of the revolution there, others would travel north to join the Lombards and Venetians in their fight against the Austrians, some would even attempt to cross the Adriatic Sea to the Balkans bringing their liberal ideals and nationalistic fervor with them.

The Kingdom of Greece was generally quite during the opening months of 1848 as economic stagnation and crop failures were comprised the worst concerns of the Greek Government. There was some unrest in April as students from the University of Athens advocated for various economic and social reforms, but nothing notable came of them aside from the lowering of the poll tax from 10 Drachma to 5 and the abolishment of all remaining restrictions on the press that had been holdovers from the Kapodistrias and Metaxas years. The Ottoman Empire was also relatively stable during this time aside from some provincial disputes and murmurs of nationalistic discontent. The Ottoman Empire’s vassals, the Danubian Principalities and the Principality of Serbia, were quite active as nationalists and liberals began advocating for greater autonomy and the liberation of their people from foreign oppression with increasing tenacity. By far though, the most active community in the Balkans during the opening months of the 1848 Revolutions were the Eptanesians of the Ionian Islands.

The Eptanesians were especially susceptible to the nationalistic and liberal messaging of the Neapolitan revolutionaries. For generations, the Ionian Islands had been under the suzerainty of the Serene Republic of Venice, only to fall under the sway of first the French then the Russians and Ottomans, before returning briefly to French rule, only to then fall under the protection of the British after the Napoleonic Wars. Established as the United States of the Ionian Islands, the Eptanesians were a de facto vassal of the British Empire, providing the Royal Navy with warm water ports in the Eastern Mediterranean all year long in return for a sizeable degree of autonomy in their internal affairs. This situation was generally amenable to the Eptanesians initially as they enjoyed some degree of local autonomy compared to their countrymen on the mainland. However, over time the British would erode the freedom of the Eptanesians, effectively reducing them to a British Colony in all but name. They deployed British soldiers on their islands and patrolled their coastlines with British ships, they controlled Eptanesian foreign and domestic policy, and they governed the islands with British administrators appointed not from Corfu, but from London.

This British occupation would unfortunately worsen following the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821. Using their wealth and resources, the Eptanesians would provide invaluable support to the Greek Revolutionaries during the Greek War of Independence, with some of the great leaders of the war emerging from the Islands like the remarkable Strategos Panos Kolokotronis and the former Greek Prime Minister Andreas Metaxas. Numerous weapons, funds, and men were funneled through the islands, much to the aggravation of the British Government which remained decidedly neutral, if not somewhat hostile towards the Greeks during the first years of the conflict. Several ships laden with provisions for the Greek Revolutionaries were unfortunately confiscated by the British authorities over the course of the war, leading to a building resentment between the British and the Eptanesians that would only worsen after the war’s end.

Although it would be slow at first, a movement clamoring for enosis, union with Greece began to emerge on the island after the end of the war in 1830. Demonstrations calling for union with Greece were a common occurrence in the various cities of the Ionian Islands, and measures calling for union with Greece would occasionally find their way to the Ionian Parliament, where they were swiftly voted down by the British dominated legislature. This situation would change in late October 1847, as the many disunited groups clamoring for union with Greece would coalesce to form the Kómma ton Rizospastón (the Party of Radicals), which campaigned on the promise of union with Greece. The Party of Radicals would prove to be a significant thorn in the side of the British Governor of the Ionian Islands, Lord High Commisioner John Colborne, 1st Baron Seaton.

The Party of Radicals (Kómma ton Rizospastón)

They organized protests against the continued British rule on the island and they purposefully boycotted British goods in favor of local Eptanesian products or Hellenic imports. The Party’s popularity among the people would earn them several seats within the Ionian Parliament where they began pushing their measures for enosis with greater effectiveness. These efforts were strongly opposed by the British Authorities on the islands who promptly arrested and imprisoned various Eptanesian MPs and unionists on the islands for seditious activity and treason against the Crown prompting mass unrest and riots across the islands. The arrival of several Neapolitan revolutionaries from Bari in late April 1848 would only serve to further destabilize the British’s hold on the islands as protests calling for union with Greece only intensified in the wake of the MP’s arrests.

Under orders from London to keep the peace on the islands, Baron Seaton declared martial law over the Ionian Islands and instated a curfew in Kerkyra (Corfu city). He forcibly closed various Radical newspapers, and he would even deport prominent Unionists from the islands. When these acts proved insufficient in ending the demonstrations, Seaton ordered the hanging of a handful of violent offenders for their behavior as a warning against further unrest. These acts by the British, would only worsen the demonstrations against them, leading to a gradual collapse in British rule on the islands. The British actions would also bring about stern condemnation from the Greek Government which issued a diplomatic complaint.

The events on the Ionian Islands were of little consequence to the British Government however. While the unrest was certainly unfortunate and unwanted, their focus was directed elsewhere, namely across the Channel in the lands of the now defunct Kingdom of Belgium and across the narrow sea in Ireland where famine and discontent reigned supreme. There was also the matter of Persia, which had defied British demands to vacate Afghanistan, necessitating a response by Parliament. War with the Persian Shah was undesirable, but it now seemed unavoidable given his recalcitrance and his continued propagation of war in the region. More worrying were reports of Russian aggression in Central Asia, as they had established forts along the Syr river and were fielding steamships in the Aral Sea.

The British were also embroiled in their own problems as the Charterists boldly made their move in mid-April. According to reports, some 150,000 men, women, and children had attended the Charterist assembly at Kennington Commons on the 12th, in a show of force meant to press the British Parliament into accepting their petition for reform. The Government in response assembled nearly 100,000 policemen, soldiers, and constables to maintain the peace and prevent any acts of aggression by the crowd. The Charterists were generally peaceful and the event came and went without much concern, nevertheless it provided quite the scare for the British government. With their attention diverted elsewhere, it came as no surprise that the events on the Ionian Islands were given little attention by the British Government, effectively leaving the matter for another time.

Next Time: Prussian Blues

[1] Based on the Four Pressing Demands by Gustave Struve.

[2] Metternich is in slightly better standing ITTL thanks to the lesser scale of the Belgian Revolution compared to the French Revolution of OTL. While there are still calls for his resignation, they are fewer and farer between enabling him to just barely remain in power for now. But he will soon wish he hadn’t.

[3] Karl Ludwig, Count of Ficquelmont was a prominent supporter of Metternich and had been appointed as chancellor of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia in 1847 to improve the Empire’s standing in the region. However, with the start of the Revolutions of 1848, he was recalled to Vienna and took part in the government following Metternich’s resignation until he too was forced to resign due to his association with Metternich. As Metternich has remained in power ITTL, Ficquelmont was sent back to Lombardy-Venetia to resume his earlier work of shoring up Austrian interests there.

Last edited:

I doubt it, given that there is no way that that could end well for Greece. Even if (through some miracle) they were able to win, they would have permanently damaged relations with a Great Power. It seems more likely that it leads to a diplomatic spat which, if Greece is lucky and the British are distracted by internal problems or other European affairs, results in a peaceful enosis.Tell me if I am wrong are you hinting at a war between Greece and Britain?!

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan League

Share: