Unfortunately, King Charles being King Charles, there really isn't anyway to avoid the July Revolution of 1830 without some pretty drastic changes to Charles personality which won't be happening with a POD in Greece in 1822. The man was a committed absolutist and reactionary, who was set in his ways long before the start of this timeline. As such he will have his conflict with the Parliament and he will most likely try to dissolve it if it opposes him, leading to the enactment of the July Ordinances and the start of the revolution. Granted, he could have handled the events of the Revolution better, but there again he will have the same thinking as his OTL counterpart and probably make a lot of the same decisions that ended up costing him and his family his throne.Always makes me a bit sad to see the Restoration fail, but as long as Charles is on the throne it's probably inevitable.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueYeah I know, I wasn't trying to suggest any changes to your TL, its just a pet peeve of mine to see Charles undo all of his brother's hard work over and over, either when I'm reading about the period or alternate timelines here. As long as Charles becomes King the Bourbons are screwed. The only positive thing one can take away from Charles was that he knew when to give up, and that he didn't try to make the army brutally retake Paris.Unfortunately, King Charles being King Charles, there really isn't anyway to avoid the July Revolution of 1830 without some pretty drastic changes to Charles personality

Last edited:

Quick Ottomans the other powers are killing each other Modernize! Modernize quicker than you did before! You have to modernize and get your revenge on Egypt, France, Russia and Greece!

Chapter 40: A Pyre for the Carbonari

Chapter 40: A Pyre for the Carbonari

The Expulsion of the Austrians from Bologna

The defeat of the Austrian army on the banks of the River Po near Parma sent shockwaves throughout Italy as would be revolutionaries emerged by the thousands across the breadth and width of the Italian countryside. Seizing upon this victory, the Carbonari of the Papal Legations formed the United Italian Provinces (Provincie Unite Italiane) on the 5th of January with its capital established in the city of Bologna and made clear their aspirations of liberating all of Italy from foreign powers. Lest all of the Italian Peninsula succumb to the fires of revolution, the Austrians needed to respond quickly and overwhelmingly. And so, 60,000 soldiers of the Austrian army were dispatched to Northern Italy under the command of General Johann Maria Philip Frimont.[1] Also accompanying the army was the Duke of Reichstadt, Oberstleutnant Franz Bonaparte, or as he was more famously known, Napoleon II.

Napoleon II was the son and heir of Napoleon Bonaparte, the infamous French Emperor and General who tore Europe asunder with his audacious military campaigns and his brilliant victories against all of Europe. Born in France on the 11th of March 1811, Napoleon II had originally succeeded his father as Emperor of the French in 1814 only to be ousted by the arrival of King Louis XVIII and the Coalition forces in May. Napoleon II along with his mother, Marie-Louise were sent to the Austrian Empire following Napoleon’s first defeat in 1814 and would never see his father again. While in Vienna, Napoleon II, or Franz as his Hapsburg family called him, was systematically cleansed of his previous identity as Crown Prince of the French Empire. Every connection to his father was removed, every connection to his life in France, was removed, he was even removed from the care of his mother who was sent to Parma leaving him alone in Vienna with his Hapsburg cousins and Grandfather who all eyed him with suspicion. While he was permitted to join the military as an officer, he was relegated to ceremonial units and garrison duty in Vienna out of fear of emulating his great father.

The campaign into Northern Italy would prove to be his first venture outside of Vienna in nearly 17 years, and his first foray away from the claustrophobic control of Chancellor Klemens von Metternich. Even then, however, he remained under the specter of Metternich’s watchful gaze as his Franz’s commanding officer, Oberst Lamezan-Salins sent dispatches to the Chancellor every day. Franz and his unit were held in the rear of the force near General Frimont and his staff during the entire march from Austria to Mantua leaving him with little prospects of fighting in the war. In essence, he had traded the gilded cage of the Imperial Palace in Vienna for a more spartan environment in the army. Every aspect of his day was under close surveillance and every action he took was recorded by his superiors with scrupulous details, all of which made its way to Metternich in one form or another. Still they could not stop him from seeing everything going on around him.

Large swaths of land in Northern and Central Italy had fallen to the Revolutionaries. Much of the Papal Legations had been ceded peacefully from the Papal officials to the revolutionaries, Parma had fallen by coup, and the Duchy of Modena had seemingly sided with the Carbonari. Another gaggle of Carbonari and rabble rousers under the former Napoleonic war colonel Giuseppe Sercognani were marching on the city of Rome having already captured the cities of San Leo, Urbino, Ancona, and Spoleto. There was even word of an attempted uprising in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, although it was put down before it could progress any further. Reports of French soldiers at the Battle of the River Po near Parma, however, had proven to be the most alarming to the Imperial court in Vienna.[2] Should France intervene on the side of the Italian rebels, then Europe would once more be plunged into a terrible war. As such all available military units were to be sent to the front in Italy posthaste to destroy the Italian insurrection before France could interfere.

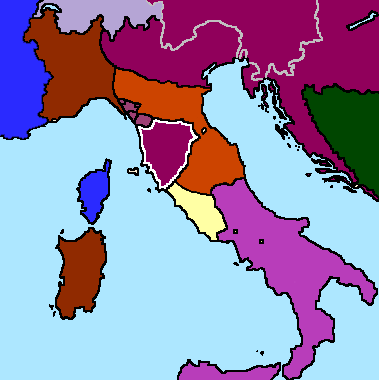

The United Italian Provinces (Orange)

While the Austrians marched into Mantua, an Italian army of Carbonari and revolutionaries marched on the township of Rieti East of Rome. The man in charge of this force, General Giuseppe Sercognani, had served in the Cisalpine Republic and then later in Eugene de Beauharnais’ Kingdom of Italy during the Napoleonic Wars. After its collapse in 1814, Sercognani remained in the service of his home city of Pesaro when it was returned to the Papal States with the Congress of Vienna. However, he retained his liberal and nationalist views, and became an early supporter of the Carbonari. Following the outbreak of the revolution in Italy, Sercognani led Pesaro in revolt against the Papal authorities, seizing the city for the Carbonari and the United Italian Provinces. With Pesaro and the Romagna secured for the Revolution, he then turned south towards the Marche and Umbria which soon fell before him and his men.

Sercognani’s advance into the legations of Rieti and Viterbo would prove to be more contested than those to the East and North as the Papal army under Cardinal Giuseppe Albani arrived to combat them. Cardinal Albani was tasked by Pope Gregory XVI with restoring order to the Legations and crushing the rebellion. On the 10th of March, Sercognani and 3,800 revolutionaries engaged Cardinal Albani and 3,200 papal militiamen near the city of Rieti. What followed was an inconclusive affair. While Albani and the Papal army were forced to cede the field to Sercognani and the rebels, the Revolutionaries had taken more losses than their opponent with 471 dead, 892 wounded, and another 188 captured or missing, compared to Albani’s 230 dead, 705 wounded, and 206 captured or missing. Still, the road was clear to Rome, but with his losses, Sercognani could do little more than shoot at the city’s walls with his muskets and rifles as he had no cannons to reduce Rome’s walls. His efforts to starve the city or terrorize it into submission met with little succession and soon signs of malaria began to appear among his men.

In the North, the Italians efforts met with similar results as the Romagnan General Carlo Zucchi led 6,000 men across the Po in a thrust towards the city of Chioggia. Before he could move to besiege the city, however, Zucchi was confronted by the vanguard of Austrian General Frimont’s army who swiftly relieved Chioggia, forcing the Italians to retreat across the Po. To the West, the Count of Santarosa met with more success capturing Pavia without a fight in early February and taking neighboring Cremona after a brief siege at the end of the month. However, Milan remained stoutly opposed to Santarosa and his men, forcing the Piedmontese General to lay siege to the city. The Italian Revolutionaries would make little progress before reports of the new Austrian army reached his camp in early March. Recognizing the disparity between his forces and the Austrians, Santarosa was forced to call on Louis-Philippe to aid the Italians as he had promised the year prior.

The formal request for support by Santarosa, however, put King Louis-Philippe in a bind. While he could get away with allowing volunteers to travel to Italy, he could not risk openly sending French soldiers to Italy, lest he risk a war with Austria. Britain also opposed any move by the French to aid the Italians, with the Canningite government threatening war unless Louis-Philippe stayed his hand from intervening. Unwilling to jeopardize his still fragile position in France, Louis-Philippe went back on his word and refused to send official aid to the Carbonari. While he allowed his own revolutionaries and dissidents to travel to Italy by the hundreds, the official disavowing of the Italians was a disheartening blow to the rebel’s cause. With aid from France no longer a viable option, Santarosa was forced to turn to the Kingdom of Sardinia and its new King Charles Albert.

King Louis-Philippe of France (Left) and King Charles Albert of Sardinia (Right)

For Santarosa to turn to Charles Albert was a serious show of desperation on his part following the latter’s betrayal in 1821. Santarosa had been a minor noble in the Kingdom of Sardinia following the Napoleonic Wars, serving faithfully as a member of the court and military in the wake of those tumultuous time. He was somewhat of a liberal in his political leanings and he was incredibly supportive of a united and independent Italy, free from the influence of Austria. And so, he and a group of like-minded individuals plotted to establish a constitution upon the Kingdom and to aid the Neapolitans in their ongoing Revolution in the South of Italy. Santarosa’s intermediary during this venture was the King’s cousin, Charles Albert who was himself relatively supportive of the venture and offered his aid to the would-be revolutionaries. Sadly, for Santarosa and his allies, Charles Albert had a crisis of conscious and turned on Santarosa forcing him to flee into exile in 1821. Charles Albert would himself later become King of Sardinia following the death of his cousin the childless King Charles Felix in early March forcing Santarosa to negotiate with the very man who betrayed him.

Charles Albert for his part wasn’t against the notion of expanding his Kingdom at the expense of Austria. However, he had more pressing issues at the time than antagonizing the Austrians, namely the resurgence of revolutionary activity in France. The July Revolution in France had alarmed Charles Albert and his predecessor Charles Felix who feared the return of French dominance over his Kingdom as had happened following the previous revolution in France in 1798. As such he had begun negotiations with Austria regarding a defensive alliance against France in the event of an invasion of Piedmont. More importantly, Charles Albert had a personal connection to Austria through his wife Maria Theresa, who was the niece of the Austrian Emperor Francis II through her father Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany. After a brief diplomatic exchange, it was clear to Santarosa that Charles Albert and Sardinia would sooner fight against him than alongside him.

With no aid forthcoming and an opposing Austrian army incoming, Santarosa’s position outside Milan had become untenable and he was forced to withdraw back across the Po, ceding control of Pavia and Cremona to General Mengen and the Austrians. Old General Frimont kept advancing, however, and managed to catch Santarosa’s force to the East of Piacenza near the commune of Caorso. Despite gathering over 13,000 volunteers and militiamen from across Lombardy, Piedmont, Parma, along with several hundred Frenchmen and Poles, Santarosa’s force was greatly outnumbered nearly 4 to 1 as Frimont had come West from Mantua to Piacenza with most of his force. The Piedmontese General, however, had managed to quickly cross the Po River ahead of the Austrians putting it between him and them.

The battle of Piacenza began at 4:00 PM on the 5th of April when two companies of Lombard riflemen under the command of a captain Carlo Cattaneo fired upon a squadron of Hungarian Hussars as they approached the ford. The hussars were soon followed by full battalion of horsemen who came charging down on Captain Cattaneo who was similarly reinforced by a brigade of French and Polish volunteers under the leadership of the Polish general Guiseppe Grabinski. Soldier after soldier went racing to the fight near the river crossing, turning what had originally begun as a skirmish into a pitched battle between the two armies. Santarosa to his credit had managed to destroy several of the nearby bridges and stationed men near the remaining river crossings to challenge any attempts by Frimont’s men to cross the river elsewhere. He could not guard every crossing, however, given his immensely smaller army and his lack of cavalry, and eventually a battalion of Austrian light infantry did succeed in crossing the Po downstream of Cremona by days end.

Battle of Piacenza

Their flank now exposed, Santarosa was compelled to retreat once more, but in doing so he would risk losing his force to desertion. Seeking to claw victory from the jaws of defeat, the Count of Santarosa placed his hopes and those of Italy on a desperate gamble, he would stage a night attack. With darkness falling and the river now definitively under Mengen’s control, Santarosa and 5,000 men were forced to make a dangerous trek back across the Po river in the dead of night. Some men were pulled beneath the water by the swift current and dashed against the rocks, but generally most of Santarosa’s men managed to traverse the river with the aid of local herders and boatmen. Unfortunately, they were soon discovered upon reaching the Northern bank of the river, but rather than retreat, Santarosa and the Italians plunged into the Austrians with all the might they could muster.

Outnumbered and now surrounded the Italians pushed deeper and deeper into the Austrian camp while their enemy was still somewhat confused as to the events going on around them. Santarosa, despite the hopelessness of the situation held true to his cause and pressed onwards towards General Frimont’s command tent in the vain hope he could capture or kill the enemy commander. Taking the lead on the charge, Annibale Santorre di Rossi de Pomarolo, the Count of Santarosa inspired his men to follow him into the jaws of death itself as he attempted to hack his way through the assembled Austrian soldiers. Sadly, he would not get very far before being cut down in a hail of bullets. The last thing the Count of Santarosa would see before passing was an immaculate young man on horseback with golden hair and wearing the white uniform of an Austrian colonel.

For the Duke of Reichstadt, the battle of Piacenza would be his first and only battle of the war. His unit had been held in reserve during the day with Franz serving in a purely observatorial role thus far, but the sudden attack by the Italians under the Count of Santarosa had done away with that. Due to the chaos of the battle, the Duke of Reichstadt quickly became separated from his handlers and was forced to fight for his life in the engagement which saw the destruction of a large portion of his force as they defiantly held their ground against the Italian rebels. At the battles peak, young Franz’s horse took a shot to the chest sending it plummeting to the ground, with its rider in tow, after which, he was not seen from again. The official report to Vienna was that Oberstleutnant Franz Bonaparte had fallen in battle fighting against the Italian revolutionaries at Piacenza. Unofficially, however, it was believed that he may have survived the engagement but his immediate whereabouts following the defeat of the Italians at Piacenza were unknown.

Napoleon Francois Charles Joseph Bonaparte "Franz", Duke of Reichstadt

Though the Italians had inflicted terrible losses on the Austrians at Piacenza; 2,300 dead, 7,800 wounded, and another 1,022 captured or missing, the Italians had suffered much worse with 5,301 dead including Santarosa, an unknown number of wounded, and nearly 4,200 were captured, of which the officers and firebrand revolutionaries would later be executed. With the death of Santarosa, the Italian cause in Parma effectively collapsed. In Modena, the disaffected Duke Francis IV seeing the writing on the wall and increasingly agitated by the overly liberal and republican tendencies of the Revolutionaries had had enough and turned on his Carbonari allies. His soldiers were ordered to round up any and all Carbonari members in Modena including their leader Ciro Menotti. A shootout occurred in the streets of Modena as Menotti and his Carbonari followers were forced to flee the city. The Italians revolutionaries would meet with a similar fate to the South and East.

Outside Rome, General Sercognani was losing men by the hundreds to disease and desertion as the dismaying reports from the north reached his camp. By early April, his force had dwindled to a little over 1,500 men and was quickly overwhelmed by Cardinal Albani’s men when they sortied against him. Though Sercognani would manage to escape capture, the revolution was effectively dead in Lazio and Umbria. In the Marche and the Romagna, it would continue for a time under General Zucchi, but with Parma and Modena freed from the Revolutionaries, the Austrians directed all their resources against their capital of Bologna. Despite their valor the Italians were quickly forced to surrender Bologna, then Ferrara, Forli, and Ravenna in quick succession. Faced with the prospect of defeat and needless loss of life, the remaining cities of the United Italian Provinces surrendered to the Austrian and Papal forces.

Before the surrender of the Italians final stronghold at Ancona in early June, many of their prominent supporters, were forced to flee the country in any way that they could. Chief among them being the British adventurer and poet Lord Byron, the former King of Holland Napoleon Louis, and his younger brother Louis Napoleon. Those foreign nationals that remained behind were quickly arrested by the Papal and Austrian authorities and sentenced to death, although at the insistence of the French government and King Louis Philippe, their sentences were commuted. Duke Francis of Modena would be permitted to retain his crown after claiming coercion by the rebels and throwing himself at the Emperor’s mercy. Many Italians revolutionaries were not as fortunate. The gallows of Lombardy-Venetia were particularly busy with a little over 800 revolutionaries meeting their ends on the hangman’s noose. By the end of July 1831, the Revolution in Italy was effectively dead and the Carbonari along with it.

Next Time: Roi de Belgique

[1] Despite being 72 years old at the start of 1831, Frimont was the Austrian commander who quashed the OTL 1830-1831 Italian revolt. He is extremely knowledgeable of Italy from his many years of service there during the Napoleonic Wars and he was stationed in Venice before the uprising. For these same reasons he is leading the effort in TTL as well.

[2] The Count of Santarosa had Frenchmen in his company at the battle of the River Po near Parma. Generally, though, these men were volunteers rather than actual French soldiers. Still, the presence either officially or unofficially of Frenchmen in Italy is not good news for Austria.

The Expulsion of the Austrians from Bologna

Napoleon II was the son and heir of Napoleon Bonaparte, the infamous French Emperor and General who tore Europe asunder with his audacious military campaigns and his brilliant victories against all of Europe. Born in France on the 11th of March 1811, Napoleon II had originally succeeded his father as Emperor of the French in 1814 only to be ousted by the arrival of King Louis XVIII and the Coalition forces in May. Napoleon II along with his mother, Marie-Louise were sent to the Austrian Empire following Napoleon’s first defeat in 1814 and would never see his father again. While in Vienna, Napoleon II, or Franz as his Hapsburg family called him, was systematically cleansed of his previous identity as Crown Prince of the French Empire. Every connection to his father was removed, every connection to his life in France, was removed, he was even removed from the care of his mother who was sent to Parma leaving him alone in Vienna with his Hapsburg cousins and Grandfather who all eyed him with suspicion. While he was permitted to join the military as an officer, he was relegated to ceremonial units and garrison duty in Vienna out of fear of emulating his great father.

The campaign into Northern Italy would prove to be his first venture outside of Vienna in nearly 17 years, and his first foray away from the claustrophobic control of Chancellor Klemens von Metternich. Even then, however, he remained under the specter of Metternich’s watchful gaze as his Franz’s commanding officer, Oberst Lamezan-Salins sent dispatches to the Chancellor every day. Franz and his unit were held in the rear of the force near General Frimont and his staff during the entire march from Austria to Mantua leaving him with little prospects of fighting in the war. In essence, he had traded the gilded cage of the Imperial Palace in Vienna for a more spartan environment in the army. Every aspect of his day was under close surveillance and every action he took was recorded by his superiors with scrupulous details, all of which made its way to Metternich in one form or another. Still they could not stop him from seeing everything going on around him.

Large swaths of land in Northern and Central Italy had fallen to the Revolutionaries. Much of the Papal Legations had been ceded peacefully from the Papal officials to the revolutionaries, Parma had fallen by coup, and the Duchy of Modena had seemingly sided with the Carbonari. Another gaggle of Carbonari and rabble rousers under the former Napoleonic war colonel Giuseppe Sercognani were marching on the city of Rome having already captured the cities of San Leo, Urbino, Ancona, and Spoleto. There was even word of an attempted uprising in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, although it was put down before it could progress any further. Reports of French soldiers at the Battle of the River Po near Parma, however, had proven to be the most alarming to the Imperial court in Vienna.[2] Should France intervene on the side of the Italian rebels, then Europe would once more be plunged into a terrible war. As such all available military units were to be sent to the front in Italy posthaste to destroy the Italian insurrection before France could interfere.

The United Italian Provinces (Orange)

While the Austrians marched into Mantua, an Italian army of Carbonari and revolutionaries marched on the township of Rieti East of Rome. The man in charge of this force, General Giuseppe Sercognani, had served in the Cisalpine Republic and then later in Eugene de Beauharnais’ Kingdom of Italy during the Napoleonic Wars. After its collapse in 1814, Sercognani remained in the service of his home city of Pesaro when it was returned to the Papal States with the Congress of Vienna. However, he retained his liberal and nationalist views, and became an early supporter of the Carbonari. Following the outbreak of the revolution in Italy, Sercognani led Pesaro in revolt against the Papal authorities, seizing the city for the Carbonari and the United Italian Provinces. With Pesaro and the Romagna secured for the Revolution, he then turned south towards the Marche and Umbria which soon fell before him and his men.

Sercognani’s advance into the legations of Rieti and Viterbo would prove to be more contested than those to the East and North as the Papal army under Cardinal Giuseppe Albani arrived to combat them. Cardinal Albani was tasked by Pope Gregory XVI with restoring order to the Legations and crushing the rebellion. On the 10th of March, Sercognani and 3,800 revolutionaries engaged Cardinal Albani and 3,200 papal militiamen near the city of Rieti. What followed was an inconclusive affair. While Albani and the Papal army were forced to cede the field to Sercognani and the rebels, the Revolutionaries had taken more losses than their opponent with 471 dead, 892 wounded, and another 188 captured or missing, compared to Albani’s 230 dead, 705 wounded, and 206 captured or missing. Still, the road was clear to Rome, but with his losses, Sercognani could do little more than shoot at the city’s walls with his muskets and rifles as he had no cannons to reduce Rome’s walls. His efforts to starve the city or terrorize it into submission met with little succession and soon signs of malaria began to appear among his men.

In the North, the Italians efforts met with similar results as the Romagnan General Carlo Zucchi led 6,000 men across the Po in a thrust towards the city of Chioggia. Before he could move to besiege the city, however, Zucchi was confronted by the vanguard of Austrian General Frimont’s army who swiftly relieved Chioggia, forcing the Italians to retreat across the Po. To the West, the Count of Santarosa met with more success capturing Pavia without a fight in early February and taking neighboring Cremona after a brief siege at the end of the month. However, Milan remained stoutly opposed to Santarosa and his men, forcing the Piedmontese General to lay siege to the city. The Italian Revolutionaries would make little progress before reports of the new Austrian army reached his camp in early March. Recognizing the disparity between his forces and the Austrians, Santarosa was forced to call on Louis-Philippe to aid the Italians as he had promised the year prior.

The formal request for support by Santarosa, however, put King Louis-Philippe in a bind. While he could get away with allowing volunteers to travel to Italy, he could not risk openly sending French soldiers to Italy, lest he risk a war with Austria. Britain also opposed any move by the French to aid the Italians, with the Canningite government threatening war unless Louis-Philippe stayed his hand from intervening. Unwilling to jeopardize his still fragile position in France, Louis-Philippe went back on his word and refused to send official aid to the Carbonari. While he allowed his own revolutionaries and dissidents to travel to Italy by the hundreds, the official disavowing of the Italians was a disheartening blow to the rebel’s cause. With aid from France no longer a viable option, Santarosa was forced to turn to the Kingdom of Sardinia and its new King Charles Albert.

King Louis-Philippe of France (Left) and King Charles Albert of Sardinia (Right)

For Santarosa to turn to Charles Albert was a serious show of desperation on his part following the latter’s betrayal in 1821. Santarosa had been a minor noble in the Kingdom of Sardinia following the Napoleonic Wars, serving faithfully as a member of the court and military in the wake of those tumultuous time. He was somewhat of a liberal in his political leanings and he was incredibly supportive of a united and independent Italy, free from the influence of Austria. And so, he and a group of like-minded individuals plotted to establish a constitution upon the Kingdom and to aid the Neapolitans in their ongoing Revolution in the South of Italy. Santarosa’s intermediary during this venture was the King’s cousin, Charles Albert who was himself relatively supportive of the venture and offered his aid to the would-be revolutionaries. Sadly, for Santarosa and his allies, Charles Albert had a crisis of conscious and turned on Santarosa forcing him to flee into exile in 1821. Charles Albert would himself later become King of Sardinia following the death of his cousin the childless King Charles Felix in early March forcing Santarosa to negotiate with the very man who betrayed him.

Charles Albert for his part wasn’t against the notion of expanding his Kingdom at the expense of Austria. However, he had more pressing issues at the time than antagonizing the Austrians, namely the resurgence of revolutionary activity in France. The July Revolution in France had alarmed Charles Albert and his predecessor Charles Felix who feared the return of French dominance over his Kingdom as had happened following the previous revolution in France in 1798. As such he had begun negotiations with Austria regarding a defensive alliance against France in the event of an invasion of Piedmont. More importantly, Charles Albert had a personal connection to Austria through his wife Maria Theresa, who was the niece of the Austrian Emperor Francis II through her father Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany. After a brief diplomatic exchange, it was clear to Santarosa that Charles Albert and Sardinia would sooner fight against him than alongside him.

With no aid forthcoming and an opposing Austrian army incoming, Santarosa’s position outside Milan had become untenable and he was forced to withdraw back across the Po, ceding control of Pavia and Cremona to General Mengen and the Austrians. Old General Frimont kept advancing, however, and managed to catch Santarosa’s force to the East of Piacenza near the commune of Caorso. Despite gathering over 13,000 volunteers and militiamen from across Lombardy, Piedmont, Parma, along with several hundred Frenchmen and Poles, Santarosa’s force was greatly outnumbered nearly 4 to 1 as Frimont had come West from Mantua to Piacenza with most of his force. The Piedmontese General, however, had managed to quickly cross the Po River ahead of the Austrians putting it between him and them.

The battle of Piacenza began at 4:00 PM on the 5th of April when two companies of Lombard riflemen under the command of a captain Carlo Cattaneo fired upon a squadron of Hungarian Hussars as they approached the ford. The hussars were soon followed by full battalion of horsemen who came charging down on Captain Cattaneo who was similarly reinforced by a brigade of French and Polish volunteers under the leadership of the Polish general Guiseppe Grabinski. Soldier after soldier went racing to the fight near the river crossing, turning what had originally begun as a skirmish into a pitched battle between the two armies. Santarosa to his credit had managed to destroy several of the nearby bridges and stationed men near the remaining river crossings to challenge any attempts by Frimont’s men to cross the river elsewhere. He could not guard every crossing, however, given his immensely smaller army and his lack of cavalry, and eventually a battalion of Austrian light infantry did succeed in crossing the Po downstream of Cremona by days end.

Battle of Piacenza

Their flank now exposed, Santarosa was compelled to retreat once more, but in doing so he would risk losing his force to desertion. Seeking to claw victory from the jaws of defeat, the Count of Santarosa placed his hopes and those of Italy on a desperate gamble, he would stage a night attack. With darkness falling and the river now definitively under Mengen’s control, Santarosa and 5,000 men were forced to make a dangerous trek back across the Po river in the dead of night. Some men were pulled beneath the water by the swift current and dashed against the rocks, but generally most of Santarosa’s men managed to traverse the river with the aid of local herders and boatmen. Unfortunately, they were soon discovered upon reaching the Northern bank of the river, but rather than retreat, Santarosa and the Italians plunged into the Austrians with all the might they could muster.

Outnumbered and now surrounded the Italians pushed deeper and deeper into the Austrian camp while their enemy was still somewhat confused as to the events going on around them. Santarosa, despite the hopelessness of the situation held true to his cause and pressed onwards towards General Frimont’s command tent in the vain hope he could capture or kill the enemy commander. Taking the lead on the charge, Annibale Santorre di Rossi de Pomarolo, the Count of Santarosa inspired his men to follow him into the jaws of death itself as he attempted to hack his way through the assembled Austrian soldiers. Sadly, he would not get very far before being cut down in a hail of bullets. The last thing the Count of Santarosa would see before passing was an immaculate young man on horseback with golden hair and wearing the white uniform of an Austrian colonel.

For the Duke of Reichstadt, the battle of Piacenza would be his first and only battle of the war. His unit had been held in reserve during the day with Franz serving in a purely observatorial role thus far, but the sudden attack by the Italians under the Count of Santarosa had done away with that. Due to the chaos of the battle, the Duke of Reichstadt quickly became separated from his handlers and was forced to fight for his life in the engagement which saw the destruction of a large portion of his force as they defiantly held their ground against the Italian rebels. At the battles peak, young Franz’s horse took a shot to the chest sending it plummeting to the ground, with its rider in tow, after which, he was not seen from again. The official report to Vienna was that Oberstleutnant Franz Bonaparte had fallen in battle fighting against the Italian revolutionaries at Piacenza. Unofficially, however, it was believed that he may have survived the engagement but his immediate whereabouts following the defeat of the Italians at Piacenza were unknown.

Napoleon Francois Charles Joseph Bonaparte "Franz", Duke of Reichstadt

Though the Italians had inflicted terrible losses on the Austrians at Piacenza; 2,300 dead, 7,800 wounded, and another 1,022 captured or missing, the Italians had suffered much worse with 5,301 dead including Santarosa, an unknown number of wounded, and nearly 4,200 were captured, of which the officers and firebrand revolutionaries would later be executed. With the death of Santarosa, the Italian cause in Parma effectively collapsed. In Modena, the disaffected Duke Francis IV seeing the writing on the wall and increasingly agitated by the overly liberal and republican tendencies of the Revolutionaries had had enough and turned on his Carbonari allies. His soldiers were ordered to round up any and all Carbonari members in Modena including their leader Ciro Menotti. A shootout occurred in the streets of Modena as Menotti and his Carbonari followers were forced to flee the city. The Italians revolutionaries would meet with a similar fate to the South and East.

Outside Rome, General Sercognani was losing men by the hundreds to disease and desertion as the dismaying reports from the north reached his camp. By early April, his force had dwindled to a little over 1,500 men and was quickly overwhelmed by Cardinal Albani’s men when they sortied against him. Though Sercognani would manage to escape capture, the revolution was effectively dead in Lazio and Umbria. In the Marche and the Romagna, it would continue for a time under General Zucchi, but with Parma and Modena freed from the Revolutionaries, the Austrians directed all their resources against their capital of Bologna. Despite their valor the Italians were quickly forced to surrender Bologna, then Ferrara, Forli, and Ravenna in quick succession. Faced with the prospect of defeat and needless loss of life, the remaining cities of the United Italian Provinces surrendered to the Austrian and Papal forces.

Before the surrender of the Italians final stronghold at Ancona in early June, many of their prominent supporters, were forced to flee the country in any way that they could. Chief among them being the British adventurer and poet Lord Byron, the former King of Holland Napoleon Louis, and his younger brother Louis Napoleon. Those foreign nationals that remained behind were quickly arrested by the Papal and Austrian authorities and sentenced to death, although at the insistence of the French government and King Louis Philippe, their sentences were commuted. Duke Francis of Modena would be permitted to retain his crown after claiming coercion by the rebels and throwing himself at the Emperor’s mercy. Many Italians revolutionaries were not as fortunate. The gallows of Lombardy-Venetia were particularly busy with a little over 800 revolutionaries meeting their ends on the hangman’s noose. By the end of July 1831, the Revolution in Italy was effectively dead and the Carbonari along with it.

Next Time: Roi de Belgique

[1] Despite being 72 years old at the start of 1831, Frimont was the Austrian commander who quashed the OTL 1830-1831 Italian revolt. He is extremely knowledgeable of Italy from his many years of service there during the Napoleonic Wars and he was stationed in Venice before the uprising. For these same reasons he is leading the effort in TTL as well.

[2] The Count of Santarosa had Frenchmen in his company at the battle of the River Po near Parma. Generally, though, these men were volunteers rather than actual French soldiers. Still, the presence either officially or unofficially of Frenchmen in Italy is not good news for Austria.

Last edited:

I really REALLY want for Napoleon's son to survive, if only to re-ignite the legacy of his father.

I second this! Having an earlier Napoleon restoration would be so interesting!

So the Hapsburg crown just went and executed several thousand rebels that had surrendered in battle? Yes that's going to be received so well all over Europe even by reactionaries. That on top of Santaroza and his Italians heroically dying at Piacenza. And come to think of it Byron is still around to be inspired by both.

The pan-European Liberal conspiracy Metternich fantasized about, couldn't be producing better anti-absolutist propaganda if they tried...

The pan-European Liberal conspiracy Metternich fantasized about, couldn't be producing better anti-absolutist propaganda if they tried...

I second this! Having an earlier Napoleon restoration would be so interesting!

I'm getting that odd suspicion... Napoleon king of the Belgians?

I'm getting that odd suspicion... Napoleon king of the Belgians?

That would just be sad.

Belgium is called Belgique in French. So it would be "Roi de Belgique" ou "Roi des Belges".

Otherwise, a great update.

Otherwise, a great update.

Isnt it "Roi des Belges" because the belgian king is king of the belgians, rather than of belgium.Belgium is called Belgique in French. So it would be "Roi de Belgique" ou "Roi des Belges".

Otherwise, a great update.

Yes. But it could go either way.Isnt it "Roi des Belges" because the belgian king is king of the belgians, rather than of belgium.

To be fair, the aftermath of the OTL Italian insurrections often resulted in a lot of hangings and firing squads. Generally though, it was the leaders of the insurrections who were executed, so I will probably revise that number down somewhat to something more appropriate.So the Hapsburg crown just went and executed several thousand rebels that had surrendered in battle? Yes that's going to be received so well all over Europe even by reactionaries. That on top of Santaroza and his Italians heroically dying at Piacenza. And come to think of it Byron is still around to be inspired by both.

The pan-European Liberal conspiracy Metternich fantasized about, couldn't be producing better anti-absolutist propaganda if they tried...

I have plans for young Napoleon that will include Belgium, but not in the way that you might think.I'm getting that odd suspicion... Napoleon king of the Belgians?

Belgium is called Belgique in French. So it would be "Roi de Belgique" ou "Roi des Belges".

Otherwise, a great update.

You are both correct. The appropriate title for King of the Belgians is Roi des Belges and King of Belgium is Roi de Belgique. That error is my failed attempt at being cute with a language I have no real experience in so thank you for bringing it to my attention it is now fixed.Isnt it "Roi des Belges" because the belgian king is king of the belgians, rather than of belgium.

I have plans for young Napoleon that will include Belgium, but not in the way that you might think.

Napoleon II conquers Belgium!!!

Given OTL trends I expect this to be the spark for Italian nationalism that eventually kicks out the foreigners... on the other hand, there’s always the small chance the Austrians keep their power, which would be really wild.

Napoleon only conquers Wallonia and gives Flanders to the Netherlands, finally restoring Western Europe to its natural state

/s

Napoleon II conquers Belgium!!!

Napoleon only conquers Wallonia and gives Flanders to the Netherlands, finally restoring Western Europe to its natural state

/s

The European powers will never allow Napoléon II to rule Belgium, especially not Louis-Philippe.

Who said anything about letting?The European powers will never allow Napoléon II to rule Belgium, especially not Louis-Philippe.

Who said anything about letting?

Do you want to start the Second Napoleonic Wars? Because that's how you start the Second Napoleonic Wars

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan League

Share: