Anatolia's definitely in the cards in the early 20th century. The Levant and Italy is definitely less possible.Yeah, I would go even farther than you and add that Anatolia and the Levant just aren't in the cards either. Also, I don't think that southern Italy foray is plausible at all.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueWestern Anatolia is definitely in the cards. Levant and south Italy? Hell no.Yeah, I would go even farther than you and add that Anatolia and the Levant just aren't in the cards either. Also, I don't think that southern Italy foray is plausible at all.

When does Corinth Canal open? And how much will Greece benefit from it?

Last edited:

In 1862 as stated in the last updated,aside from the tolls greece will benefit immensely due to easier transportation and communication between eastern and western greece as strategic advantage aswell..now on the long term depends on how wide the canal will be in the future.When does Corinth Canal open? And how much will Greece benefit from it?

Last edited:

I mean, if the British are footing the bill this time around it might well end up a bit wider. They had to deal with rockslides in otl thoughIn 1862 as stated in the last updated,aside from the tolls greece will benefit immensely due to easier transportation and communication between eastern and western greece as a stratigraphic aswell..now on the long term depends on how wide the canal will be in the future.

I do wonder what Greece's industry will look like compared to other nations of the time, they'll certainly be better off than their Balkan neighbors but how much is my question... It's mostly oriented around shipbuilding at this point right? I wonder where they might diversify down the road... The earlier they industrialize the better off they'll be economically after all.

Chapter 92: A Game of Gods and Men

Author's Note:

Surprise, I have a new chapter ready for you all! I had originally intended to post this a few days ago to coincide with the recent Olympic Games Closing Ceremony, but I had some technical difficulties and eventually decided to delay it.

Anyway, before we get to the Chapter, I'll quickly opine on some recent topics of debate you all had.

Revolts in the Ottoman Empire:

Yes there will be more revolts in the Ottoman Empire, that is the nature of the beast. That said, I won't spoil where they will happen and what the results will be as that isn't any fun. If you really want to know and don't want to wait then PM me and I'll spoil you rotten.

Greek Economy:

The Greek economy is in a very good position to flourish and expand even more. Sadly, that trend won't last forever and eventually there will be economic stagnation, recessions, and depressions in Greece's future. That being said, if Greece manages these correctly, then it shouldn't be too bad.

Greek Expansion:

In terms of priorities for Greek expansion, number one on the list is clearly Constantinople, followed closely by Macedonia - specifically Thessaloniki and the area surrounding it. Next is the Aegean coast of Anatolia, then probably the Straits region, with the remaining coastline of Anatolia coming in after that, then maybe more of Albania and the Balkans. At the bottom of that list is Southern Italy. Point being, Greece is more interested in expanding eastward than it is westward. While there are certainly Greco communities still living in Southern Italy at this time ITTL, Athens would sooner expand into North Africa than Southern Italy.

Chapter 92: A Game of Gods and Men

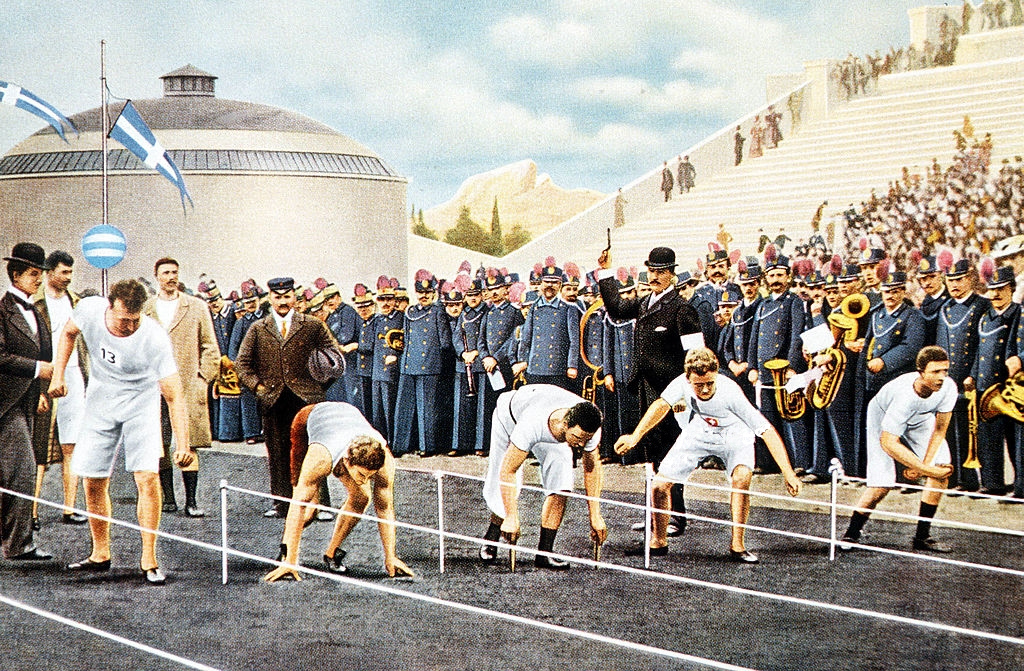

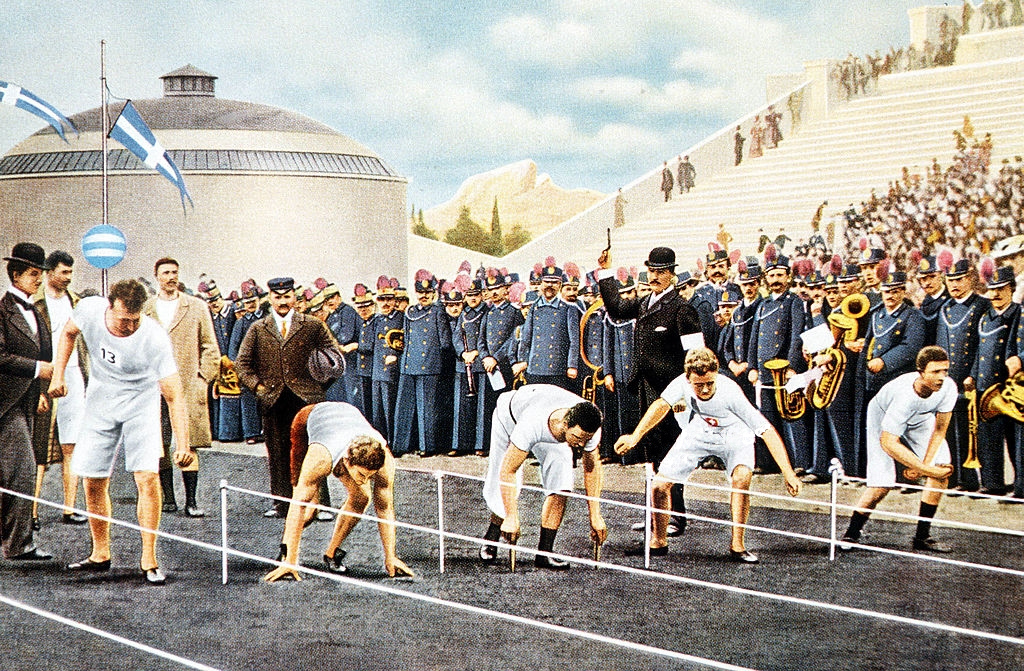

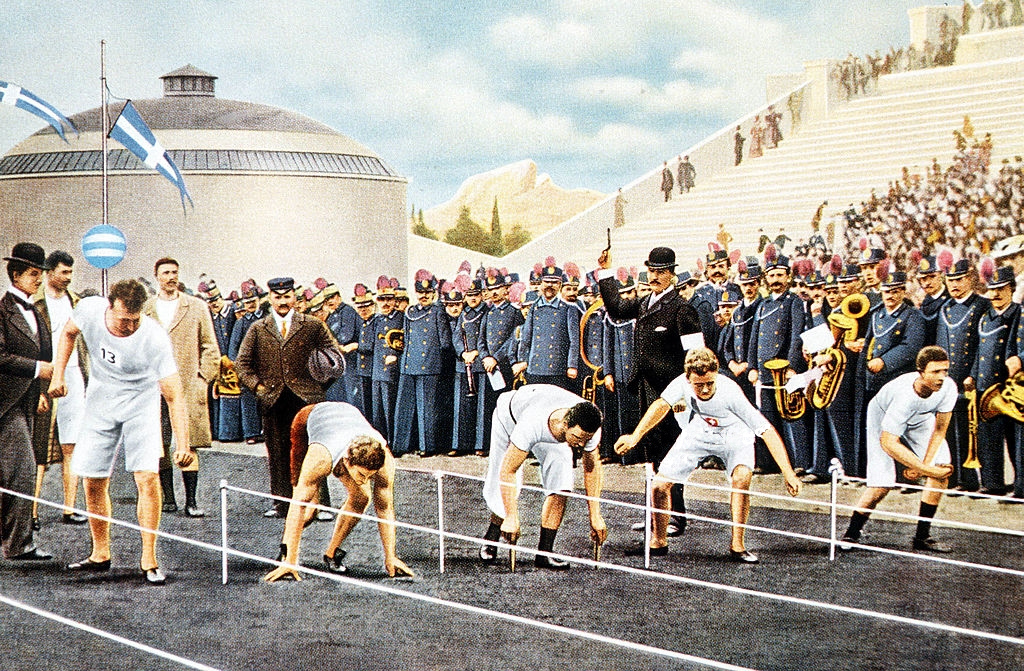

Athletes line up for the running of the 100 meter dash at the 1866 Olympic Games

Today we celebrate the beginning of the 39th Summer Olympic Games, a contest of great athleticism where athletes from all across the globe journey to one select site to due battle against one another for glory and gold. However, these battles are not done with swords and spears or guns and artillery, but with feats of strength, speed, and intellect. Putting everything on the line, these competitors risk it all for a chance at being the best in the world for their respective fields. To be an Olympic Champion is a great honor for all who earn it. Yet, there is so much more to the Olympics Games than a simple entertainment extravaganza held every four years, as their history dates back to the Greek Dark Ages nearly 2800 years ago.

Far from the simple athletic event that it is today, the Ancient Olympics were more so a religious ceremony hosted in honor of the Olympian Gods. The host site of the Ancient Olympic Games was in the Elian city of Olympia, which was first and foremost a city of temples dedicated to Olympian Zeus and his fellow deities. Thusly, these games were not meant to entertain the mere mortals standing in attendance at rustic Olympia. No, these were displays of valor and piety before the Hellenic Gods seated high upon Mount Olympus. These contests of strength and speed and grit and determination were meant to show the often arbitrary and conceited Gods that humanity was noble and strong and deserving of their patronage.

As such, the men partaking in these contests were often honored as great champions by their respective city-states. As representatives of their home Poleis, these athletes were attended to by throngs of supporters, physicians, and sponsors who ensured that their man was in tip top shape for the Games. In the eyes of their cities, victory for their athletes meant that the Gods favored had favored them, and by favoring their champions, they favored their cities as well. Victors in these competitions were often regarded as heroes on par with the legends of yore; they were bestowed great gifts and treated to extravagant feasts at the expense of their native Polis. There were also benefits for the victorious cities as they received great prestige and influence if their athletes won in the most recent Panhellenic Games.

Finally, the Olympics were tremendous diplomatic forums where city-states made treaties and forged alliances with one another. It is important to note, however, that the Olympic Games were themselves part of the larger Panhellenic Games; with competitors journeying to one of four cities (Olympia, Delhpi, Nemea, and Isthmia) every year. These Games were held in such high esteem by the Ancient Greeks, that they usually observed a two-month truce surrounding them, despite their incredibly warlike nature. Any violators of this truce, be they friend or foe was scrutinized and shunned as a villian and oathbreaker. Over time, the Games at Olympia would grow in importance and eventually overshadow those of the other cities, owing to its glorification of the King of the Olympians, almighty Zeus.

According to the Ancient philosopher Aristotle, the first Olympic games took place in the year 776 BCE, following the Summer Solstice.[1] However, unlike later iterations of these Games, this competition consisted of a single event, a foot race known as the Stadion. The Stadion was a simple foot race of roughly 180 meters named in honor of a legendary race held between the Idei Daktiloi (the Ideal Fingers) of the Titan Queen Rhea. Charged with protecting the infant deity Zeus from the auspices of his vile father, the Titan Cronos; the Dactyls of Rhea spirited the young God from Crete to the Peloponnese. However, as they traveled the five brothers grew bored, and in their boredom, they began to fight amongst themselves.

To end their feuding, the eldest of the five, Idaios Iraklis (Ideal Herakles, not to be confused with the legendary son of Zeus) suggested that they have a race to settle their squabbles and entertain young Zeus. Agreeing to their brother’s proposal, the Five settled upon a distance of 180 meters for their contest. Readying themselves on the line, they counted down and then leapt to action with all their godly might once the call was made. Though the brothers were evenly matched, the elder Iraklis proved himself the better in their contest, winning by a hair over his younger siblings. Yet in his humility and great wisdom, Iraklis offered to race his brothers again in four years’ time, a challenge which they readily accepted. While the historical accuracy of this story is dubious at best, it nevertheless served as inspiration for the Ancient Greeks who carefully modelled their own competition off this mythical race.

Depiction of the Stadion

As the years passed, more and more sporting events would be added to the Games. The first added in 724 BCE would be the Diaulos, a foot race twice the length of the Stadion. In 720 BCE, an even longer race would be added called the Dolichos, which averaged around 1,500 meters in length. In 708 BCE another two events would be added to the Games, Wrestling and the Pentathalon; the latter of which was a myriad of contests consisting of a long jump, javelin throwing, discus throwing, a foot race comparable in length to the Stadion, and wrestling. Later Olympiads would also see the inclusion of boxing, horse racing, chariot racing and other athletic challenges to the Games. Yet, through it all the Stadion remained the most prestigious event at the Olympics, with the victor of this one event being proclaimed the winner of the entire Olympic Games.

Over time, however, later iterations of the Olympic Games would see the rise in popularity of another event; the Pankration. Pankration was a variation of wrestling with few rules and restrictions. As such, it quickly became popular among young men and boys in attendance at these Games.[2] The violence of the sport was so great that several participants were killed over the years with many others being seriously maimed and injured. Owing to this great violence, Pankration would be outlawed by the Roman Emperor Theodosius alongside gladiatorial fights and other violent displays of entertainment in the 390’s CE. In more recent years, there has been an effort to rekindle Pankration fighting at the Olympics and within Greece sporting circles in general. However, it has found its greatest success in the Hellenic Military which has adopted Pankration as part of its hand-to-hand fighting training regimen for their more elite units like the Evzones Regiments.

Despite the violence of its events, the allure of the Olympics Games was so great during its heyday that many great kings and mighty emperors would travel to Olympia and partake in the festivities. Among them was Philip II of Macedon and the Roman Emperor Nero providing a foreign element to the Event. Even brilliant Augustus himself would patronize the Olympic Games in a showing of his piety and magnamnity. Outside of these prominent monarchs, tens of thousands of commonfolk would journey to Elis over the centuries to bear witness to the great spectacles at Olympia. Yet as is the case with all things, interest in the Olympic Games would eventually wax and wane as Barbarian invasions, plagues, earthquakes, and the growing influence of Christianity slowly did away with the Olympics. Ultimately, the last recorded Games would take place in 385 CE before it finally disappeared into the annals of history forevermore.

Despite this, the legend of the Ancient Olympic Games continued to live on as various communities across Europe would stage their own variations of the competition over the centuries. The most noteworthy contests were the Cotswold Olimpick Games, held in Cotswold, England from the early 1600’s until the early 1800's. Although they bear the Olympics name, the Cotswold Games were more akin to a lowly county festival than a prestigious athletic competition as the events consisted of dancing, hunting, music making, fighting both with weapons and fists, and the occasional foot and horse race. Nevertheless, the Cotswold Games would prove quite popular attracting many visitors and attendees over the years.

Unfortunately, the Cotswold Olimpicks were not without controversy, as they featured their share of violence and brutality, with participants being maimed and even killed on a few occasions. Moreover, the event itself was often regaled by its contemporaries as a heathen festival full of drunkards and the dregs of society, greatly diminishing its reputation. Ultimately, the Cotswold Olimpicks would appear sporadically every few years from their inception in 1612 all the way until 1852 when growing controversies finally forced the shire of Cotswold to sell off the communal plots upon which the Games had taken place, effectively ending the Games once and for all.

Another competition of note was the L'Olympiade de la République held in France during the height of the French Revolution. While it was much shorter in duration, only lasting from 1796 to 1798, it would be deemed in far higher regard by historians and philosophers than the Cotswold Games. Unlike the English Cotswold Olimpicks, the L’Olympiade emulated the Ancient Games very closely, including several events such as wrestling, running, horse races, javelin throws and discus throws among others. Moreover, the Olympiade would also feature the first recorded use of the metric system in sports, with it becoming the standard across the globe for most sporting contests in the coming decades.

Whilst these precursors were certainly interesting and helped continued the legacy of the Ancient Olympic Games well into the 19th Century; the Independence of Greece in 1830 would serve as a far greater catalyst for the Olympic revival as the ancient site of the Games were now liberated after centuries of foreign occupation. For their part, many within Greece were receptive to the idea, yet many others, especially within more conservative circles opposed their resurrection. However, with the country still recovering from their War for Independence, it was ultimately a rather low priority for the Athenian Government and Greek populace as a whole who were far more interested in providing food and shelter for themselves and their families. Yet, as the country began to recover, and the people began to move on from the rigors of war and the daily struggle for survival; public support for the ancient sporting event began to rise with several prominent figures in Greek society even hosting their own interpretations of the Olympics.

The first iteration of these would be the Soutsos Games in 1836, which were organized by the renowned Greek Romanticist Panagiotis Soutsos in the ancient city of Olympia. Although he is most famous today for his poems Odiporos (the Wanderer) and Leandros, Soutsos was also a major proponent of Greek language reform towards a purer (ancient) form. This fascination with the Ancient Greek language also carried over to Ancient Greek culture, religion and; most importantly to the topic of this chapter, the Olympics. In 1835, Soutsos would release his latest work, Dialogues with the Dead, a work which glorified, among many other things, the Ancient Olympic Games. As with many of his earlier works, Dialogues would prove especially popular among certain segments of the population who began advocating for the resurrection of the Olympics in their ancient homeland.

Panagiotis Soutsos, Famed Poet and Organizer of the “First Modern Olympic Games”

Buoyed by this outpouring of support, Soutsos, along with many of his closest supporters and sponsors would form the Hellenic Olympic Society to begin advocating for the revival of the ancient sporting event. While this was a novel idea with a degree of popular support, they still had several hurdles to overcome. First was determining the site and timing of the Games. Being the romantic and purist that he was, Soutsos naturally proposed the ancient city of Olympia following the Summer Solstice just as it had been in olden times. The symbolism of the site was certainly prominent as the rebirth of the Games at Olympia would symbolize a greater revival of the Hellenic spirit. While much of the city was still a buried ruin, excavations had thankfully started in recent years, resulting in the uncovering of several stadiums at the site, bringing moderate attention to the long-neglected region.

The next issue was funding for their endeavors, with Soutsos and his colleagues reaching out to various bankers and philanthropists willing to support their work. Initially, they would receive some nominal support from the Zosimades of Ioannina, the banker Georgios Stravos, and the ambassador to Vienna Georgios Sinas among others, providing them with a quick infusion of cash to begin organizing their event. However, their efforts to gain the financial backing from other prominent Greek philanthropists such as Georgios Rizaris and Ioannis Papafis ended in failure, as they saw the ancient Games a glorification of Pagan rituals and vehemently refused to support such a sacrilegious act. Ironically, they would also meet resistance from several historians and archaeologists such as Theodoros Manousis who argued that major festivities at Olympia would endanger the preservation of the historical site. Nevertheless, Soutsos and his clique would press on with their efforts, eventually raising the necessary funds for their Olympic Games.

However, they would still need Government support, or at the very least its begrudging acquiescence for their efforts in order to host the Games at Olympia given that extensive activities would be carried out at the historic site if they had their way. Reaching out to their contacts in the Kapodistrias Administration, the Hellenic Olympic Society would find several members of the regime who were quite receptive to the idea of the Olympics, with the Minister of Internal Affairs, Viaros Kapodistrias even openly endorsing their proposals and offering to aid them in their efforts.[3] However, in doing so they quickly created more problems for themselves as Viaros Kapodistrias was known for being quite meddlesome and authoritative.

True to form, Viaros immediately began interfering in the organization of the Olympics, specifically its location and timing. Arguing that Olympia was linked too closely with the pagan rites of their forefathers, he instead proposed that the New Games be held at Athens. This made a large amount of sense as Athens was the capital of the modern Hellenic Kingdom as well as the epicenter of culture in the nascent state. Moreover, there was also the issue that Olympia was a distant and largely uninhabited village whereas Athens was quickly becoming the largest city in the country, one which was easily accessible for any prospective participants and attendees. Not done yet, Viaros also proposed that the Games be scheduled for the 25th of March, coinciding with the annual Independence Day festivities as part of a larger celebration of Greek culture and its recent victories over its adversaries.

Medals issued in 1836 commemorating the War for Independence

Ultimately, Soutsos and the Hellenic Olympic Society would eventually agree to the 25th of March, however, they vehemently refused to budge on the location of the Games believing the city of Olympia to be integral to the Olympics. Soutsos would famously quip that "the Olympics without Olympia would be akin to a ballgame without a ball." Sadly, this decision would prove to be their downfall as the site was in a rather poor state of disrepair after millennia of disuse. The general lack of infrastructure in the region also limited the number of participants and spectators willing to make the journey to rural Olympia in March 1836. Worse still there was great public discontent with the decision to link the modern Games to their ancient counterpart. Despite their considerable efforts to the contrary, many in Greek society viewed the Soutsos Games as a perverse display of Hellenic Paganism, rather than the glorification of Greek culture which Soutsos had originally envisioned.

Nevertheless, Soutsos and his supporters pressed on and after months of buildup, the day finally came. Sadly, as expected by many, the results would prove to be rather disappointing. In total there were a mere thirteen athletes at Olympia willing to participate in the Games, with a scant 784 people in attendance to cheer them on, almost all of them being from the local area. Also in attendance were a number of musicians, singers and poets who serenaded visitors with their works, whilst peddlers advertised their merchandise. To help distance these Games from their Pagan roots, whilst still respecting the religious undertones of the event; Soutsos would invite the Metropolitan Larissis Kyrillos to lead a prayer service and serve as the Games’ Master of Ceremonies.

Ironically, the pomp and circumstance surrounding the Soutsos Olympics would overshadow the Games themselves as there was only a single event at these 1836 Games, the Stadion foot race, just like the first Games of yore. The exhibitors were directed to the start line, readied themselves and jolted forward at the ringing of a gunshot. Moments later, the race was finished. The winner was a local Moreot man from Patras named Georgios Katopodis, who was described as thin and lanky by the few spectators still in attendance who were stunned to find out that the Games were over after all of a few seconds. Unimpressed by the display, many left in a huff and refused to purchase any of the merchandise being offered by the organizers, resulting in a sizeable loss in revenue for the event’s sponsors.

Unwilling to commit further resources to an apparently failed initiative, many of their investors pulled their support from the venture. Making matters worse, Viaros Kapodistrias would be transferred to the Ministry of Justice several days after the Games. His successor as Minister of Internal Affairs, Iakovos Rizos Neroulos would prove much more hostile to Soutsos and his clique leading to the formal end of Government support for the Soutsos Olympics. Nevertheless, Soutsos and a small group of his supporters would organize a second Olympic Games at Olympia four years later in 1840, however, turnout would be even smaller than the first Soutsos Games, forcing the Hellenic Olympic Society to shutter its doors later that year.

Despite its failures, the efforts of Panagiotis Soutsos and his supporters would help pave the way for future endeavors as other patrons would attempt to revitalize athletics within the Greek state. Most were local affairs that generated little publicity outside their communities. Eventually, one would emerge above the rest, as the great land magnate Evangelos Zappas would take up the torch for the Olympics several years later to great effect.

A veteran of the War for Independence, Zappas had later emigrated abroad to Wallachia where he quickly earned his fortune as a businessman, trader, and land baron. By the 1850’s, Evangelos was among the richest men in the Balkans, with a net worth of several million Drachma, whilst also establishing important connections with some of the most influential people in the region. Rather than waste his fortune on himself as many of his contemporaries did, Zappas would instead invest it in the country of Greece, serving as a great benefactor of the nascent state. He would sponsor the construction of many schools and hospitals across the country, providing cheap medical services and easy access to education for many hundreds if not thousands of Greeks. However, his greatest contributions were in arts and culture, specifically the second Greek attempt at reviving the Olympic Games.

Evangelos Zappas; Land Magnate, Philanthropist, and “Father” of the Modern Olympic Games

Like many others, Evangelos Zappas had been inspired by the poems of Panagiotis Soutsos, particularly those regarding Ancient Greece and the Olympics. He had even been a benefactor of both the 1836 and 1840 Soutsos Games, despite his admittedly minor fortune at the time. By the early 1850’s however, his financial standing was strong enough that he could organize the Games himself. At great personal expense, Zappas and his cousin Konstantinos would advocate for the revival of the Olympic Games in Greece. Fortunately for the two, the situation in Greece was vastly different than it was during the 1830’s. The country had almost completely recovered from the destructive War for Independence, the Greek economy was booming and, most importantly, there was now a greater interest in leisure activities and entertainment in Greece. While there were still those who viewed the Olympics with skepticism and mistrust owing to its Pagan history, most Greeks looked upon them more favorably, or at the very least, they didn’t oppose them to the same degree as they had over a decade before.

As such, Zappas would find relatively little public resistance to his Olympic Games, the so-called Zappas Games, which he tentatively scheduled for the Summer of 1854. Moreover, as he could finance the Games by himself, Zappas needn’t worry himself over the conflicting opinions of benefactors and sponsors, as he didn’t need any. Nor would there be any efforts to tie his Games to the Greek Independence Day celebration as Soutsos had been forced to do years before. No! His Games would stand on their own as an event unto themselves. He would do things how he wanted to do them, scheduling the games for the Month of July just as they had in the days of yore.

Yet, whilst he was a romantic at heart, Evangelos Zappas was also a prudent businessman and understood better than anyone the necessity of drawing a large crowd if his endeavor was to survive. Recognizing this, he would elect to stage his Olympic Games on the biggest stage in all of Greece, Athens. By 1854, Athens was hands down the largest city in Greece, with well over 60,000 full time residents and thousands more traveling to the city over the course of the year for work or leisure. Moreover, its infrastructure was the best in the country with the proliferation of railroads across the Attic peninsula and the enlargement of the ports of Piraeus and Laurium, easily connecting the capital city to the rest of Greece. Finally, there were also a host of possible venues within the city for his Games, with the Panathenaic being the most impressive and the most prestigious.

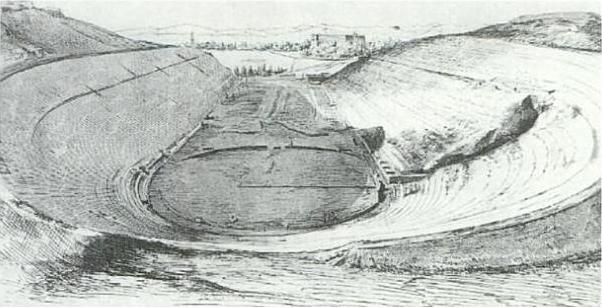

Located in central Athens, the Panathenaic was a massive stadium that could seat nearly 50,000 spectators at its height. More impressive however, was its exquisite façade, which was made entirely out of the priceless Pentelic marble, providing the building with a flawlessly white appearance. However, by Zappas’ day it was little more than a half-buried ruin, as raiders and occupiers had looted the site for its riches and left the stadium derelict millennia ago. There had been some efforts to excavate the site, specifically when the architects Kleanthis and Schaubert had renovated Athens during the late 1830’s and early 1840’s, yet it still remained in disrepair by the early 1850's.

This would not deter Zappas, however, as he swiftly reached out to his compatriot the Representative of Athens, Timoleon Filliman to lobby the Hellenic Government on his behalf. After greasing some palms, agreeing to extensive government oversight of the site’s excavation, and promising to keep the original design of the stadium largely intact; Zappas was finally given permission to begin restoration work at the Panathenaic. All this did not come cheaply, however, as the Hellenic Government maintained a monopoly on the priceless Pentelic Marble, and only produced it to interested parties at an incredibly high cost and only for projects they approved of. They also required that great care be exercised when digging at the Panathenaic to not endanger any artifacts that may be found, resulting in numerous delays and shutdowns whilst priceless relics were uncovered, documented, and then carefully removed from the site for safekeeping. Ultimately, the Panathenaic would not be ready in time for the 1854 Games, forcing the event to be relocated to the nearby Constitution Square for the duration of that year’s event.

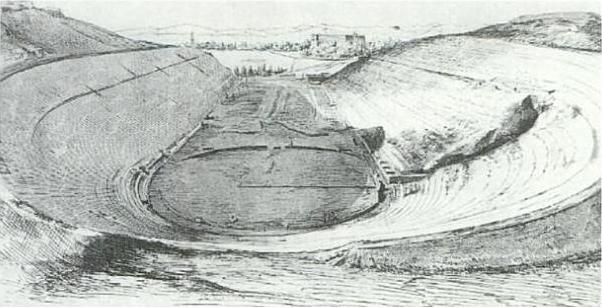

The Panathenaic as it appeared during the Summer of 1854

Despite this setback, the Panathenaic would feature prominently in the opening and closing ceremonies for the First Zappas Games and in several of the Competition's award celebrations. A factor working in Zappas' favor was that unlike the Soutsos Games of 1836 and 1840, these Games would feature a multitude of events including the Stadion (a 192-meter foot race) and the Dolichos (a 1354-meter foot race), discus and javelin throwing, long jumping, and wrestling. However, as sporting was still an uncommon pastime in mid-19th Century Greece, the contenders came from a wide variety of backgrounds and professions. Some were farmers or laborers, others were lawyers or bureaucrats, a few were soldiers or sailors, and a handful were even teachers and clergymen signaling a complete shift in public opinion from the Soutsos Games. There are even five recorded instances of policemen charged with patrolling the Square, who temporarily abandoned their posts to join in various events. More incredibly, however, was the account of a well-known blind beggar, who “miraculously” regained his vision in time to join in the running of the Dolichos and finished in a remarkable 4th place.[4]

Many participants were attracted by the rather generous rewards awarded to the winners, with those finishing in first place in their respective competitions receiving 200 Drachma and an olive wreath to celebrate their victory. Those finishing in second or third place received lesser prizes of 100 Drachma and 50 Drachma respectively, both of which were still considerable amounts for the average worker at the time who barely made a quarter that sum in a month. Overall, over one hundred and eighty men would compete in the 1854 Olympic Games with nearly 30,000 people visiting the grounds over the three day event including Prime Minister Constantine Kanaris, Prince Constantine and Prince Alexander. Needless to say, the first Zappas Games were a surprising success.

No sooner had the 1854 Games concluded did Zappas and his deputies begin planning a second Olympic Games, which were tentatively scheduled for the Summer of 1858. Before then, however, they had much work to do. First and foremost, the restoration of the Panathenaic needed to be completed as the leading complaint from most spectators were the poor views from the hastily erected stands and seats in Constitution Square. To that end, work at the ancient stadium was quickened, with the site being fully cleared of dirt and debris by October of 1856, the track was re-leveled in the Summer of 1957, while the repair of its stands was completed by May of the following year. Overall, Zappas would spend upwards of half a million Drachma on the restoration and renovation of the Panathenaic between 1852 and 1858.

Zappas and his supporters would also begin efforts to standardize and professionalize the events at their Second Olympic Games. While amateurs spontaneously joining competitions on a whim had its benefits as many people were drawn to the Games for a chance to win the cash prizes; they also had their drawbacks as it lessened the quality of the Games themselves. There were several instances of bumbling buffoons and drunkards taking part in numerous events in which they had no right to partake in. Ultimately, their inclusion only made a mockery of the entire spectacle, much to the humiliation of Zappas and his fellows. To rectify this changes were needed to ensure the quality of the competitors was improved.

There after, Zappas and his conglomerate would formally establish the Hellenic Olympic Committee (Ellinikí Olympiakí Epitropí) which would govern the running and organization of all future Olympic Games. The EOE would require that all participants in their Games announce their intentions at least three months in advance, thus preventing any similar instances from happening again. Whilst this would lead to some backlash from some segments of the Greek press who lauded the First Game for its great openness to the public, most approved of the measure citing it as an improvement. Moreover, this measure would ensure that only the most truly committed athletes entered into the Games.

Finally, to further the appeal of the Games, Zappas and his Committee would expand the number of events from the original six (the Stadion, Dolichos, discus throwing, javelin throwing, long jumping, and wrestling) to eleven. These new additions were a 400-meter race roughly equivalent to the ancient Diaulos, a high jump, a Triple jump, Pole Climbing, and the Pentathlon. Whilst some would also advocate for the return of Pankration, the Marathon, and horse races in keeping with the past, others pushed for the inclusion of new events like shooting contests, bicycle races and swims of various distances. Ultimately, it was decided that further events would be added in future Games if the interest was there for them. With these changes enacted and work on the Panathenaic completed, the Second Zappas Olympic Games was ready to commence on the 11th of July 1858.

Like the 1854 Games, the Second Zappas Olympics would prove to be immensely popular with nearly 50,000 people attending over the course of the weeklong contest including King Leopold, Prime Minister Kanaris, and Prince Constantine among many others. Also in attendance were a number of foreign dignitaries and diplomats, including the exiled Prince of Serbia, Mihailo Obrenovic, the former UK Ambassador to Greece and current Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, Lord Edmund Lyons, and his successor in the post, Sir Thomas Wyse. However, owing to the more restrictive application process for this year’s Games, only 64 athletes would participate in these Games as opposed to the 181 contestants four years earlier. Most of these competitors were from the local region, with nearly 36 coming from Athens alone. Still, they would see a multitude of competitors from all across Greece travel to the Panathenaic to compete for their chance at glory.

Six days of competition would follow as athletes battled for victory in their respective competitions until only one stood atop all the rest in their field. Ultimately, the event would end on the 17th of July with surprisingly little fanfare. While critics would praise Zappas and the HOC for the better venue and for establishing more events; they would argue that the 58 Games, whilst certainly more organized, were also a more sterilized and lethargic version of the 54 Games. Many prospective exhibitors were turned away at the gates, apparently not knowing of the rule changes regarding athletes. Nevertheless, most looked upon this competition with optimism as a promising step in the right direction. Moreover, these Olympic Games would also see the first usage of medallions for those competitors finishing in first place for their respective competitions. Whilst these games would not be memorable as the First Zappas Games or the one immediately after; they were still well regarded by the press and people of Greece at the time.

Seeking to improve the level of competition even further, Zappas and the EOE would establish a fund which would be doled out to athletes upon their qualification. These funds would support said athletes, providing them food and housing in Athens provided they dedicate themselves to training for their specific field. Additional funding would be put aside to establish a formal gymnasium in Athens – the Gymnasterion, which would be comparable to those facilities found across Germany, France and the United Kingdom. There, athletes could train in a controlled environment where they could hone their skills to the best of their ability.

Other changes would include the issuing of matching uniforms for participants to improve the cohesion and professional image of the attending athletes. These included a white tunic with blue stripes and a matching pair of white shorts/pants depending on personal preference. The awarding of medals to the victors was also well received by the public. To expand upon this, athletes finishing in first place would receive a gold coated medallion, while lesser medals of silver and copper would also be provided to those athletes finishing in second and third place respectively. An official Olympic Hymn was written for the Opening and Closing ceremonies for the Game, whilst festivities and celebrations were scheduled in the days leading up to the Games themselves.

Finally, another 13 events would be added to preexisting 11 events for the 1862 Games. They included three new foot races a 100-meter foot race, a 5000-meter foot race, and a Marathon race akin to the ancient Marathon of Pheidippides. Additionally, three hurdle races were included at distances of 110-meters, 200-meters, and 400 meters. Other new events included a shot-put competition, a fencing competition, two shooting events; one with handguns at 25 meters and the other with rifles at 200 meters, and three freestyle swimming events of 100-meters, 200-meters, and 400-meters. For the swimming events, it was decided that participants would swim in the nearby Bay of Zea as they could not afford to build a specialized swimming facility in time for the next games in 1862. Instead, they would erect smaller leisure facilities, lavatories, and rest areas for attending spectators on the shoreline.

With these changes made the 1862 Olympics would begin in earnest on the 13th of July 1862. Whilst many changes had been enacted to make for a smoother and more entertaining viewing experience, the number of spectators at the opening ceremony was markedly lower in 1862 than it had been in 1858. Whereas attendance had been at an impressive 50,000 people at the Second Olympic Games four years earlier, only around 41,000 attended the Third Games. To the EOE’s credit, however, the number of participating athletes was more than double that of 1858, with nearly 160 exhibitors at the Panathenaic on the First day of the Games.

Of particular note were the inclusion of 7 Britons in the field of athletes at this year’s Games. These Englishmen were sailors and officers of the Mediterranean Fleet whose ship the HMS Warrior had been tasked with patrolling the Aegean in a show of strength after the recent War with Russia. Although their involvement in the Games was a matter of controversy at the time as non-Hellenic peoples didn’t usually participate; Zappas and the Olympic Committee had conveniently overlooked the issue when pressured by the British Ambassador Sir Thomas Wyse. Moreover, they had broken no rules or regulations when announcing their intent to participate in the Games. Overall, their involvement would have little impact on the outcome of most events, bar the rifles competition as one Englishman, Commander George Tryon would finish second behind a Greek Army Lieutenant named Ioannis Dimakopoulos.

Commander George Tryon (Left) and Lieutenant Ioannis Dimakopoulos (Right)

Controversy aside, the 1862 Games were viewed positively by Greek and foreign press resulting in an outpouring of interest from various Olympic organizations across the Globe. Although many members of the Hellenic Olympic Committee were reluctant to open up their Games to foreign athletes and foreign interests, Zappas and a number of his cohorts were more receptive to the idea and would eventually decide in favor of greater foreign involvement, starting with the 1866 Olympic Games. Sadly, Evangelos Zappas would not live to see the fourth such Games as he would die in 1865 at the age of 64. Before passing, Zappas would leave the remainder of his fortune to the Hellenic Olympic Committee, later rechristened simply as the Olympic Committee - which would establish a fund to continue the Olympic Games in his honor.

Although his death would be a hard hit to his family, friends, and colleagues; his tremendous efforts to restore the Olympic Games were simply incredible to say the least. It is no wonder then, why many consider him to be the father of the modern Olympic Games. Ultimately, the Zappas Olympic Games would continue and eventually morph into the current iteration of the Olympic Games that we know today, with the first officially recognized competition being the one held in 1866. All told, there would be over 200 athletes from eleven different countries, almost all of which were European, although 3 athletes were from the Americas (2 were from the USA and 1 was from Chile).

Since that time, the Games have only continued to grow and prosper as more countries, more athletes, and more events were added with each and every competition. Eventually, a Winter Olympics comprised of winter themed sporting events would be formed around the turn of the Century. Then later on, women would be allowed to openly participate in the Games. While these developments are worthy of their own chapters, they are beyond the scopes of this article detailing the Modern Game’s origin. Nevertheless, it is safe to say, that the Olympic Games were here to stay thanks to the considerable efforts of Evangelos Zappas, Panagiotis Soutsos, and all those preceding them.

Next Time: Mr. Smith goes to Athens

[1] There is some debate over the exact year of the first Olympic Games, with some ancient sources arguing that the Games of 776 were not the First, only that it was the first recorded. Archaeological evidence does seem to support the theory that there were earlier competitions at Olympia.

[2] There were only two rules in ancient Pankration: no biting, and no gouging of the eyes. Everything else was permitted.

[3] In OTL, Soutsos and members of the Greek government considered including an Olympic Games as part of the Independence Day celebrations. Sadly, these talks came to nothing for one reason or another. ITTL, Soutsos is more successful.

[4] This is actually based off of OTL. Apparently, the beggar in question was only pretending to be blind.

Surprise, I have a new chapter ready for you all! I had originally intended to post this a few days ago to coincide with the recent Olympic Games Closing Ceremony, but I had some technical difficulties and eventually decided to delay it.

Anyway, before we get to the Chapter, I'll quickly opine on some recent topics of debate you all had.

Revolts in the Ottoman Empire:

Yes there will be more revolts in the Ottoman Empire, that is the nature of the beast. That said, I won't spoil where they will happen and what the results will be as that isn't any fun. If you really want to know and don't want to wait then PM me and I'll spoil you rotten.

Greek Economy:

The Greek economy is in a very good position to flourish and expand even more. Sadly, that trend won't last forever and eventually there will be economic stagnation, recessions, and depressions in Greece's future. That being said, if Greece manages these correctly, then it shouldn't be too bad.

Greek Expansion:

In terms of priorities for Greek expansion, number one on the list is clearly Constantinople, followed closely by Macedonia - specifically Thessaloniki and the area surrounding it. Next is the Aegean coast of Anatolia, then probably the Straits region, with the remaining coastline of Anatolia coming in after that, then maybe more of Albania and the Balkans. At the bottom of that list is Southern Italy. Point being, Greece is more interested in expanding eastward than it is westward. While there are certainly Greco communities still living in Southern Italy at this time ITTL, Athens would sooner expand into North Africa than Southern Italy.

Chapter 92: A Game of Gods and Men

Athletes line up for the running of the 100 meter dash at the 1866 Olympic Games

Today we celebrate the beginning of the 39th Summer Olympic Games, a contest of great athleticism where athletes from all across the globe journey to one select site to due battle against one another for glory and gold. However, these battles are not done with swords and spears or guns and artillery, but with feats of strength, speed, and intellect. Putting everything on the line, these competitors risk it all for a chance at being the best in the world for their respective fields. To be an Olympic Champion is a great honor for all who earn it. Yet, there is so much more to the Olympics Games than a simple entertainment extravaganza held every four years, as their history dates back to the Greek Dark Ages nearly 2800 years ago.

Far from the simple athletic event that it is today, the Ancient Olympics were more so a religious ceremony hosted in honor of the Olympian Gods. The host site of the Ancient Olympic Games was in the Elian city of Olympia, which was first and foremost a city of temples dedicated to Olympian Zeus and his fellow deities. Thusly, these games were not meant to entertain the mere mortals standing in attendance at rustic Olympia. No, these were displays of valor and piety before the Hellenic Gods seated high upon Mount Olympus. These contests of strength and speed and grit and determination were meant to show the often arbitrary and conceited Gods that humanity was noble and strong and deserving of their patronage.

As such, the men partaking in these contests were often honored as great champions by their respective city-states. As representatives of their home Poleis, these athletes were attended to by throngs of supporters, physicians, and sponsors who ensured that their man was in tip top shape for the Games. In the eyes of their cities, victory for their athletes meant that the Gods favored had favored them, and by favoring their champions, they favored their cities as well. Victors in these competitions were often regarded as heroes on par with the legends of yore; they were bestowed great gifts and treated to extravagant feasts at the expense of their native Polis. There were also benefits for the victorious cities as they received great prestige and influence if their athletes won in the most recent Panhellenic Games.

Finally, the Olympics were tremendous diplomatic forums where city-states made treaties and forged alliances with one another. It is important to note, however, that the Olympic Games were themselves part of the larger Panhellenic Games; with competitors journeying to one of four cities (Olympia, Delhpi, Nemea, and Isthmia) every year. These Games were held in such high esteem by the Ancient Greeks, that they usually observed a two-month truce surrounding them, despite their incredibly warlike nature. Any violators of this truce, be they friend or foe was scrutinized and shunned as a villian and oathbreaker. Over time, the Games at Olympia would grow in importance and eventually overshadow those of the other cities, owing to its glorification of the King of the Olympians, almighty Zeus.

According to the Ancient philosopher Aristotle, the first Olympic games took place in the year 776 BCE, following the Summer Solstice.[1] However, unlike later iterations of these Games, this competition consisted of a single event, a foot race known as the Stadion. The Stadion was a simple foot race of roughly 180 meters named in honor of a legendary race held between the Idei Daktiloi (the Ideal Fingers) of the Titan Queen Rhea. Charged with protecting the infant deity Zeus from the auspices of his vile father, the Titan Cronos; the Dactyls of Rhea spirited the young God from Crete to the Peloponnese. However, as they traveled the five brothers grew bored, and in their boredom, they began to fight amongst themselves.

To end their feuding, the eldest of the five, Idaios Iraklis (Ideal Herakles, not to be confused with the legendary son of Zeus) suggested that they have a race to settle their squabbles and entertain young Zeus. Agreeing to their brother’s proposal, the Five settled upon a distance of 180 meters for their contest. Readying themselves on the line, they counted down and then leapt to action with all their godly might once the call was made. Though the brothers were evenly matched, the elder Iraklis proved himself the better in their contest, winning by a hair over his younger siblings. Yet in his humility and great wisdom, Iraklis offered to race his brothers again in four years’ time, a challenge which they readily accepted. While the historical accuracy of this story is dubious at best, it nevertheless served as inspiration for the Ancient Greeks who carefully modelled their own competition off this mythical race.

Depiction of the Stadion

Over time, however, later iterations of the Olympic Games would see the rise in popularity of another event; the Pankration. Pankration was a variation of wrestling with few rules and restrictions. As such, it quickly became popular among young men and boys in attendance at these Games.[2] The violence of the sport was so great that several participants were killed over the years with many others being seriously maimed and injured. Owing to this great violence, Pankration would be outlawed by the Roman Emperor Theodosius alongside gladiatorial fights and other violent displays of entertainment in the 390’s CE. In more recent years, there has been an effort to rekindle Pankration fighting at the Olympics and within Greece sporting circles in general. However, it has found its greatest success in the Hellenic Military which has adopted Pankration as part of its hand-to-hand fighting training regimen for their more elite units like the Evzones Regiments.

Despite the violence of its events, the allure of the Olympics Games was so great during its heyday that many great kings and mighty emperors would travel to Olympia and partake in the festivities. Among them was Philip II of Macedon and the Roman Emperor Nero providing a foreign element to the Event. Even brilliant Augustus himself would patronize the Olympic Games in a showing of his piety and magnamnity. Outside of these prominent monarchs, tens of thousands of commonfolk would journey to Elis over the centuries to bear witness to the great spectacles at Olympia. Yet as is the case with all things, interest in the Olympic Games would eventually wax and wane as Barbarian invasions, plagues, earthquakes, and the growing influence of Christianity slowly did away with the Olympics. Ultimately, the last recorded Games would take place in 385 CE before it finally disappeared into the annals of history forevermore.

Despite this, the legend of the Ancient Olympic Games continued to live on as various communities across Europe would stage their own variations of the competition over the centuries. The most noteworthy contests were the Cotswold Olimpick Games, held in Cotswold, England from the early 1600’s until the early 1800's. Although they bear the Olympics name, the Cotswold Games were more akin to a lowly county festival than a prestigious athletic competition as the events consisted of dancing, hunting, music making, fighting both with weapons and fists, and the occasional foot and horse race. Nevertheless, the Cotswold Games would prove quite popular attracting many visitors and attendees over the years.

Unfortunately, the Cotswold Olimpicks were not without controversy, as they featured their share of violence and brutality, with participants being maimed and even killed on a few occasions. Moreover, the event itself was often regaled by its contemporaries as a heathen festival full of drunkards and the dregs of society, greatly diminishing its reputation. Ultimately, the Cotswold Olimpicks would appear sporadically every few years from their inception in 1612 all the way until 1852 when growing controversies finally forced the shire of Cotswold to sell off the communal plots upon which the Games had taken place, effectively ending the Games once and for all.

Another competition of note was the L'Olympiade de la République held in France during the height of the French Revolution. While it was much shorter in duration, only lasting from 1796 to 1798, it would be deemed in far higher regard by historians and philosophers than the Cotswold Games. Unlike the English Cotswold Olimpicks, the L’Olympiade emulated the Ancient Games very closely, including several events such as wrestling, running, horse races, javelin throws and discus throws among others. Moreover, the Olympiade would also feature the first recorded use of the metric system in sports, with it becoming the standard across the globe for most sporting contests in the coming decades.

Whilst these precursors were certainly interesting and helped continued the legacy of the Ancient Olympic Games well into the 19th Century; the Independence of Greece in 1830 would serve as a far greater catalyst for the Olympic revival as the ancient site of the Games were now liberated after centuries of foreign occupation. For their part, many within Greece were receptive to the idea, yet many others, especially within more conservative circles opposed their resurrection. However, with the country still recovering from their War for Independence, it was ultimately a rather low priority for the Athenian Government and Greek populace as a whole who were far more interested in providing food and shelter for themselves and their families. Yet, as the country began to recover, and the people began to move on from the rigors of war and the daily struggle for survival; public support for the ancient sporting event began to rise with several prominent figures in Greek society even hosting their own interpretations of the Olympics.

The first iteration of these would be the Soutsos Games in 1836, which were organized by the renowned Greek Romanticist Panagiotis Soutsos in the ancient city of Olympia. Although he is most famous today for his poems Odiporos (the Wanderer) and Leandros, Soutsos was also a major proponent of Greek language reform towards a purer (ancient) form. This fascination with the Ancient Greek language also carried over to Ancient Greek culture, religion and; most importantly to the topic of this chapter, the Olympics. In 1835, Soutsos would release his latest work, Dialogues with the Dead, a work which glorified, among many other things, the Ancient Olympic Games. As with many of his earlier works, Dialogues would prove especially popular among certain segments of the population who began advocating for the resurrection of the Olympics in their ancient homeland.

Panagiotis Soutsos, Famed Poet and Organizer of the “First Modern Olympic Games”

Buoyed by this outpouring of support, Soutsos, along with many of his closest supporters and sponsors would form the Hellenic Olympic Society to begin advocating for the revival of the ancient sporting event. While this was a novel idea with a degree of popular support, they still had several hurdles to overcome. First was determining the site and timing of the Games. Being the romantic and purist that he was, Soutsos naturally proposed the ancient city of Olympia following the Summer Solstice just as it had been in olden times. The symbolism of the site was certainly prominent as the rebirth of the Games at Olympia would symbolize a greater revival of the Hellenic spirit. While much of the city was still a buried ruin, excavations had thankfully started in recent years, resulting in the uncovering of several stadiums at the site, bringing moderate attention to the long-neglected region.

The next issue was funding for their endeavors, with Soutsos and his colleagues reaching out to various bankers and philanthropists willing to support their work. Initially, they would receive some nominal support from the Zosimades of Ioannina, the banker Georgios Stravos, and the ambassador to Vienna Georgios Sinas among others, providing them with a quick infusion of cash to begin organizing their event. However, their efforts to gain the financial backing from other prominent Greek philanthropists such as Georgios Rizaris and Ioannis Papafis ended in failure, as they saw the ancient Games a glorification of Pagan rituals and vehemently refused to support such a sacrilegious act. Ironically, they would also meet resistance from several historians and archaeologists such as Theodoros Manousis who argued that major festivities at Olympia would endanger the preservation of the historical site. Nevertheless, Soutsos and his clique would press on with their efforts, eventually raising the necessary funds for their Olympic Games.

However, they would still need Government support, or at the very least its begrudging acquiescence for their efforts in order to host the Games at Olympia given that extensive activities would be carried out at the historic site if they had their way. Reaching out to their contacts in the Kapodistrias Administration, the Hellenic Olympic Society would find several members of the regime who were quite receptive to the idea of the Olympics, with the Minister of Internal Affairs, Viaros Kapodistrias even openly endorsing their proposals and offering to aid them in their efforts.[3] However, in doing so they quickly created more problems for themselves as Viaros Kapodistrias was known for being quite meddlesome and authoritative.

True to form, Viaros immediately began interfering in the organization of the Olympics, specifically its location and timing. Arguing that Olympia was linked too closely with the pagan rites of their forefathers, he instead proposed that the New Games be held at Athens. This made a large amount of sense as Athens was the capital of the modern Hellenic Kingdom as well as the epicenter of culture in the nascent state. Moreover, there was also the issue that Olympia was a distant and largely uninhabited village whereas Athens was quickly becoming the largest city in the country, one which was easily accessible for any prospective participants and attendees. Not done yet, Viaros also proposed that the Games be scheduled for the 25th of March, coinciding with the annual Independence Day festivities as part of a larger celebration of Greek culture and its recent victories over its adversaries.

Medals issued in 1836 commemorating the War for Independence

Nevertheless, Soutsos and his supporters pressed on and after months of buildup, the day finally came. Sadly, as expected by many, the results would prove to be rather disappointing. In total there were a mere thirteen athletes at Olympia willing to participate in the Games, with a scant 784 people in attendance to cheer them on, almost all of them being from the local area. Also in attendance were a number of musicians, singers and poets who serenaded visitors with their works, whilst peddlers advertised their merchandise. To help distance these Games from their Pagan roots, whilst still respecting the religious undertones of the event; Soutsos would invite the Metropolitan Larissis Kyrillos to lead a prayer service and serve as the Games’ Master of Ceremonies.

Ironically, the pomp and circumstance surrounding the Soutsos Olympics would overshadow the Games themselves as there was only a single event at these 1836 Games, the Stadion foot race, just like the first Games of yore. The exhibitors were directed to the start line, readied themselves and jolted forward at the ringing of a gunshot. Moments later, the race was finished. The winner was a local Moreot man from Patras named Georgios Katopodis, who was described as thin and lanky by the few spectators still in attendance who were stunned to find out that the Games were over after all of a few seconds. Unimpressed by the display, many left in a huff and refused to purchase any of the merchandise being offered by the organizers, resulting in a sizeable loss in revenue for the event’s sponsors.

Unwilling to commit further resources to an apparently failed initiative, many of their investors pulled their support from the venture. Making matters worse, Viaros Kapodistrias would be transferred to the Ministry of Justice several days after the Games. His successor as Minister of Internal Affairs, Iakovos Rizos Neroulos would prove much more hostile to Soutsos and his clique leading to the formal end of Government support for the Soutsos Olympics. Nevertheless, Soutsos and a small group of his supporters would organize a second Olympic Games at Olympia four years later in 1840, however, turnout would be even smaller than the first Soutsos Games, forcing the Hellenic Olympic Society to shutter its doors later that year.

Despite its failures, the efforts of Panagiotis Soutsos and his supporters would help pave the way for future endeavors as other patrons would attempt to revitalize athletics within the Greek state. Most were local affairs that generated little publicity outside their communities. Eventually, one would emerge above the rest, as the great land magnate Evangelos Zappas would take up the torch for the Olympics several years later to great effect.

A veteran of the War for Independence, Zappas had later emigrated abroad to Wallachia where he quickly earned his fortune as a businessman, trader, and land baron. By the 1850’s, Evangelos was among the richest men in the Balkans, with a net worth of several million Drachma, whilst also establishing important connections with some of the most influential people in the region. Rather than waste his fortune on himself as many of his contemporaries did, Zappas would instead invest it in the country of Greece, serving as a great benefactor of the nascent state. He would sponsor the construction of many schools and hospitals across the country, providing cheap medical services and easy access to education for many hundreds if not thousands of Greeks. However, his greatest contributions were in arts and culture, specifically the second Greek attempt at reviving the Olympic Games.

Evangelos Zappas; Land Magnate, Philanthropist, and “Father” of the Modern Olympic Games

Like many others, Evangelos Zappas had been inspired by the poems of Panagiotis Soutsos, particularly those regarding Ancient Greece and the Olympics. He had even been a benefactor of both the 1836 and 1840 Soutsos Games, despite his admittedly minor fortune at the time. By the early 1850’s however, his financial standing was strong enough that he could organize the Games himself. At great personal expense, Zappas and his cousin Konstantinos would advocate for the revival of the Olympic Games in Greece. Fortunately for the two, the situation in Greece was vastly different than it was during the 1830’s. The country had almost completely recovered from the destructive War for Independence, the Greek economy was booming and, most importantly, there was now a greater interest in leisure activities and entertainment in Greece. While there were still those who viewed the Olympics with skepticism and mistrust owing to its Pagan history, most Greeks looked upon them more favorably, or at the very least, they didn’t oppose them to the same degree as they had over a decade before.

As such, Zappas would find relatively little public resistance to his Olympic Games, the so-called Zappas Games, which he tentatively scheduled for the Summer of 1854. Moreover, as he could finance the Games by himself, Zappas needn’t worry himself over the conflicting opinions of benefactors and sponsors, as he didn’t need any. Nor would there be any efforts to tie his Games to the Greek Independence Day celebration as Soutsos had been forced to do years before. No! His Games would stand on their own as an event unto themselves. He would do things how he wanted to do them, scheduling the games for the Month of July just as they had in the days of yore.

Yet, whilst he was a romantic at heart, Evangelos Zappas was also a prudent businessman and understood better than anyone the necessity of drawing a large crowd if his endeavor was to survive. Recognizing this, he would elect to stage his Olympic Games on the biggest stage in all of Greece, Athens. By 1854, Athens was hands down the largest city in Greece, with well over 60,000 full time residents and thousands more traveling to the city over the course of the year for work or leisure. Moreover, its infrastructure was the best in the country with the proliferation of railroads across the Attic peninsula and the enlargement of the ports of Piraeus and Laurium, easily connecting the capital city to the rest of Greece. Finally, there were also a host of possible venues within the city for his Games, with the Panathenaic being the most impressive and the most prestigious.

Located in central Athens, the Panathenaic was a massive stadium that could seat nearly 50,000 spectators at its height. More impressive however, was its exquisite façade, which was made entirely out of the priceless Pentelic marble, providing the building with a flawlessly white appearance. However, by Zappas’ day it was little more than a half-buried ruin, as raiders and occupiers had looted the site for its riches and left the stadium derelict millennia ago. There had been some efforts to excavate the site, specifically when the architects Kleanthis and Schaubert had renovated Athens during the late 1830’s and early 1840’s, yet it still remained in disrepair by the early 1850's.

This would not deter Zappas, however, as he swiftly reached out to his compatriot the Representative of Athens, Timoleon Filliman to lobby the Hellenic Government on his behalf. After greasing some palms, agreeing to extensive government oversight of the site’s excavation, and promising to keep the original design of the stadium largely intact; Zappas was finally given permission to begin restoration work at the Panathenaic. All this did not come cheaply, however, as the Hellenic Government maintained a monopoly on the priceless Pentelic Marble, and only produced it to interested parties at an incredibly high cost and only for projects they approved of. They also required that great care be exercised when digging at the Panathenaic to not endanger any artifacts that may be found, resulting in numerous delays and shutdowns whilst priceless relics were uncovered, documented, and then carefully removed from the site for safekeeping. Ultimately, the Panathenaic would not be ready in time for the 1854 Games, forcing the event to be relocated to the nearby Constitution Square for the duration of that year’s event.

The Panathenaic as it appeared during the Summer of 1854

Despite this setback, the Panathenaic would feature prominently in the opening and closing ceremonies for the First Zappas Games and in several of the Competition's award celebrations. A factor working in Zappas' favor was that unlike the Soutsos Games of 1836 and 1840, these Games would feature a multitude of events including the Stadion (a 192-meter foot race) and the Dolichos (a 1354-meter foot race), discus and javelin throwing, long jumping, and wrestling. However, as sporting was still an uncommon pastime in mid-19th Century Greece, the contenders came from a wide variety of backgrounds and professions. Some were farmers or laborers, others were lawyers or bureaucrats, a few were soldiers or sailors, and a handful were even teachers and clergymen signaling a complete shift in public opinion from the Soutsos Games. There are even five recorded instances of policemen charged with patrolling the Square, who temporarily abandoned their posts to join in various events. More incredibly, however, was the account of a well-known blind beggar, who “miraculously” regained his vision in time to join in the running of the Dolichos and finished in a remarkable 4th place.[4]

Many participants were attracted by the rather generous rewards awarded to the winners, with those finishing in first place in their respective competitions receiving 200 Drachma and an olive wreath to celebrate their victory. Those finishing in second or third place received lesser prizes of 100 Drachma and 50 Drachma respectively, both of which were still considerable amounts for the average worker at the time who barely made a quarter that sum in a month. Overall, over one hundred and eighty men would compete in the 1854 Olympic Games with nearly 30,000 people visiting the grounds over the three day event including Prime Minister Constantine Kanaris, Prince Constantine and Prince Alexander. Needless to say, the first Zappas Games were a surprising success.

No sooner had the 1854 Games concluded did Zappas and his deputies begin planning a second Olympic Games, which were tentatively scheduled for the Summer of 1858. Before then, however, they had much work to do. First and foremost, the restoration of the Panathenaic needed to be completed as the leading complaint from most spectators were the poor views from the hastily erected stands and seats in Constitution Square. To that end, work at the ancient stadium was quickened, with the site being fully cleared of dirt and debris by October of 1856, the track was re-leveled in the Summer of 1957, while the repair of its stands was completed by May of the following year. Overall, Zappas would spend upwards of half a million Drachma on the restoration and renovation of the Panathenaic between 1852 and 1858.

Zappas and his supporters would also begin efforts to standardize and professionalize the events at their Second Olympic Games. While amateurs spontaneously joining competitions on a whim had its benefits as many people were drawn to the Games for a chance to win the cash prizes; they also had their drawbacks as it lessened the quality of the Games themselves. There were several instances of bumbling buffoons and drunkards taking part in numerous events in which they had no right to partake in. Ultimately, their inclusion only made a mockery of the entire spectacle, much to the humiliation of Zappas and his fellows. To rectify this changes were needed to ensure the quality of the competitors was improved.

There after, Zappas and his conglomerate would formally establish the Hellenic Olympic Committee (Ellinikí Olympiakí Epitropí) which would govern the running and organization of all future Olympic Games. The EOE would require that all participants in their Games announce their intentions at least three months in advance, thus preventing any similar instances from happening again. Whilst this would lead to some backlash from some segments of the Greek press who lauded the First Game for its great openness to the public, most approved of the measure citing it as an improvement. Moreover, this measure would ensure that only the most truly committed athletes entered into the Games.

Finally, to further the appeal of the Games, Zappas and his Committee would expand the number of events from the original six (the Stadion, Dolichos, discus throwing, javelin throwing, long jumping, and wrestling) to eleven. These new additions were a 400-meter race roughly equivalent to the ancient Diaulos, a high jump, a Triple jump, Pole Climbing, and the Pentathlon. Whilst some would also advocate for the return of Pankration, the Marathon, and horse races in keeping with the past, others pushed for the inclusion of new events like shooting contests, bicycle races and swims of various distances. Ultimately, it was decided that further events would be added in future Games if the interest was there for them. With these changes enacted and work on the Panathenaic completed, the Second Zappas Olympic Games was ready to commence on the 11th of July 1858.

The Panathenaic at the 1858 Olympics Opening Ceremony

Like the 1854 Games, the Second Zappas Olympics would prove to be immensely popular with nearly 50,000 people attending over the course of the weeklong contest including King Leopold, Prime Minister Kanaris, and Prince Constantine among many others. Also in attendance were a number of foreign dignitaries and diplomats, including the exiled Prince of Serbia, Mihailo Obrenovic, the former UK Ambassador to Greece and current Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, Lord Edmund Lyons, and his successor in the post, Sir Thomas Wyse. However, owing to the more restrictive application process for this year’s Games, only 64 athletes would participate in these Games as opposed to the 181 contestants four years earlier. Most of these competitors were from the local region, with nearly 36 coming from Athens alone. Still, they would see a multitude of competitors from all across Greece travel to the Panathenaic to compete for their chance at glory.

Six days of competition would follow as athletes battled for victory in their respective competitions until only one stood atop all the rest in their field. Ultimately, the event would end on the 17th of July with surprisingly little fanfare. While critics would praise Zappas and the HOC for the better venue and for establishing more events; they would argue that the 58 Games, whilst certainly more organized, were also a more sterilized and lethargic version of the 54 Games. Many prospective exhibitors were turned away at the gates, apparently not knowing of the rule changes regarding athletes. Nevertheless, most looked upon this competition with optimism as a promising step in the right direction. Moreover, these Olympic Games would also see the first usage of medallions for those competitors finishing in first place for their respective competitions. Whilst these games would not be memorable as the First Zappas Games or the one immediately after; they were still well regarded by the press and people of Greece at the time.

Seeking to improve the level of competition even further, Zappas and the EOE would establish a fund which would be doled out to athletes upon their qualification. These funds would support said athletes, providing them food and housing in Athens provided they dedicate themselves to training for their specific field. Additional funding would be put aside to establish a formal gymnasium in Athens – the Gymnasterion, which would be comparable to those facilities found across Germany, France and the United Kingdom. There, athletes could train in a controlled environment where they could hone their skills to the best of their ability.

Other changes would include the issuing of matching uniforms for participants to improve the cohesion and professional image of the attending athletes. These included a white tunic with blue stripes and a matching pair of white shorts/pants depending on personal preference. The awarding of medals to the victors was also well received by the public. To expand upon this, athletes finishing in first place would receive a gold coated medallion, while lesser medals of silver and copper would also be provided to those athletes finishing in second and third place respectively. An official Olympic Hymn was written for the Opening and Closing ceremonies for the Game, whilst festivities and celebrations were scheduled in the days leading up to the Games themselves.

Finally, another 13 events would be added to preexisting 11 events for the 1862 Games. They included three new foot races a 100-meter foot race, a 5000-meter foot race, and a Marathon race akin to the ancient Marathon of Pheidippides. Additionally, three hurdle races were included at distances of 110-meters, 200-meters, and 400 meters. Other new events included a shot-put competition, a fencing competition, two shooting events; one with handguns at 25 meters and the other with rifles at 200 meters, and three freestyle swimming events of 100-meters, 200-meters, and 400-meters. For the swimming events, it was decided that participants would swim in the nearby Bay of Zea as they could not afford to build a specialized swimming facility in time for the next games in 1862. Instead, they would erect smaller leisure facilities, lavatories, and rest areas for attending spectators on the shoreline.

With these changes made the 1862 Olympics would begin in earnest on the 13th of July 1862. Whilst many changes had been enacted to make for a smoother and more entertaining viewing experience, the number of spectators at the opening ceremony was markedly lower in 1862 than it had been in 1858. Whereas attendance had been at an impressive 50,000 people at the Second Olympic Games four years earlier, only around 41,000 attended the Third Games. To the EOE’s credit, however, the number of participating athletes was more than double that of 1858, with nearly 160 exhibitors at the Panathenaic on the First day of the Games.

Of particular note were the inclusion of 7 Britons in the field of athletes at this year’s Games. These Englishmen were sailors and officers of the Mediterranean Fleet whose ship the HMS Warrior had been tasked with patrolling the Aegean in a show of strength after the recent War with Russia. Although their involvement in the Games was a matter of controversy at the time as non-Hellenic peoples didn’t usually participate; Zappas and the Olympic Committee had conveniently overlooked the issue when pressured by the British Ambassador Sir Thomas Wyse. Moreover, they had broken no rules or regulations when announcing their intent to participate in the Games. Overall, their involvement would have little impact on the outcome of most events, bar the rifles competition as one Englishman, Commander George Tryon would finish second behind a Greek Army Lieutenant named Ioannis Dimakopoulos.

Commander George Tryon (Left) and Lieutenant Ioannis Dimakopoulos (Right)

Controversy aside, the 1862 Games were viewed positively by Greek and foreign press resulting in an outpouring of interest from various Olympic organizations across the Globe. Although many members of the Hellenic Olympic Committee were reluctant to open up their Games to foreign athletes and foreign interests, Zappas and a number of his cohorts were more receptive to the idea and would eventually decide in favor of greater foreign involvement, starting with the 1866 Olympic Games. Sadly, Evangelos Zappas would not live to see the fourth such Games as he would die in 1865 at the age of 64. Before passing, Zappas would leave the remainder of his fortune to the Hellenic Olympic Committee, later rechristened simply as the Olympic Committee - which would establish a fund to continue the Olympic Games in his honor.