Yeah a Perfidious one at that since the 'west' kickstart alot of wars to keep themselves afloat. The only silver lining is that now other nations have grown and can no longer be bullied as easy as they wanted.Well for better or for worse we live in a world that is deeply influenced by the British empire

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueSure but any other People with the same power and geopolitics as the uk would act the same if not worseYeah a Perfidious one at that since the 'west' kickstart alot of wars to keep themselves afloat. The only silver lining is that now other nations have grown and can no longer be bullied as easy as they wanted.

Is it a matter of scale/size ?While certainly not the Nazis, there was no other Empire quite like the British, who left deep economic and psychological scars wherever they went, no other Empire quite so ruthlessly exploitative, no other Empire quite so free in its use of divide-and-rule politics, no other Empire quite so successful.

Regarding the most successful empire, the obvious answer is the USA. No other political entity in history has been able to achieve that political, economic and military dominance that the USA has enjoyed until very recently. The British Empire was just the world's premier seapower state, with limited ability to project power over landmasses. The USA has been the global hegemon.

Empires more ruthlessly exploitative I can name a bunch. Belgium comes in mind from modern ones. Rome trumps almost every other political entity.

Divide-and-rule politics were always part of any hegemonic power's toolkit. Many were incredible in applying it (Athens) while others were able to apply quite successfully it for more than a millenium (Egypt to Levantine states).

No empire has had a deeper economic impact than the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates. The socioeconomic model these political entities developed in a big part of the world last for centuries after their demise and became both the a reason for economic prosperity and later on, a reason for decline.

Regarding psychological scars, I cannot think more pronounced scars than erasing identities from large subject populations. A prime example is the Middle Kingdom that developed the monoculture of Han China. Or the Romans completely erasing the identity of subject peoples, those that became today's nations that speak romance languages.

The British Empire was nothing new or extreme (compared to the other empires) when we actually study history. And political theory shows that empires use the same tools to obtain their hegemony first and then keep it.

Extraordinary update, i've truely buied the indian sucess with this, it's really wonderful. I think the Dehli massacre won't be without consequences.Chapter 87: The Devil’s Wind – Part 2

No longer able to ignore the burgeoning crisis that was taking place in the Indian Subcontinent, the British Government would finally begin channeling its resources away from the Russian War and towards the Rebellion in India during the Summer of 1856. The first unit to be dispatched would be the veteran 3rd Division under the recently promoted Lieutenant General Richard England in early July. The 3rd was a battle-hardened unit that had fought against the Russians in Rumelia for the better part of two years when it was recalled to Constantinople and ordered to India. Thankfully, their long journey to the Indian Subcontinent was made much shorter thanks to the Egyptian Government of Ishmael Kavalali Pasha, which permitted the British to traverse the partially completed Suez Canal thus saving the 3rd Division well over a month of traveling.

Vengeance of the Lion

This arrangement between Alexandria and London also removed a thorny issue for both governments in the form of Abbas Pasha. In the months preceding this agreement, London had offered their support to Abbas Kavalali over his French aligned cousin, in the hopes he would win the throne and move Egypt into Britain’s sphere of influence. However, they quickly discovered that Abbas Pasha held little real popular support within Egypt – most of which came from the conservatives and the clergy who had been disaffected by Ibrahim Pasha’s modernizing rule. When it became abundantly clear to London that Abbas Pasha would never successfully claim the Khedivate throne, the British quickly withdrew their support and made amends with Alexandria in return for a few minor concessions from Ishmael Pasha’s government (the right to traverse the Suez being one of the most notable).

Ishmael was quite happy to agree to the British request as it removed a potential threat to his rule, while also providing an opportunity to test his new canal which had just recently reached Lake Timsah, roughly corresponding to the halfway point for the project. From there, however, the British troops would be forced to march across the remainder of the Isthmus arriving at the port of Suez three days later. Finally, the soldiers of the 3rd Division would board new ships at Suez and arrive at the port town of Karachi before the end of July. Yet, after their rigorous journey across the Suez Isthmus and 19 months of constant campaigning in the Balkans; its troops were exhausted, and its ranks were depleted. As such, it would require several weeks to recuperate, re-arm and reinforce before they would be battle ready once again.

The arrival of the 3rd Division would be followed several weeks later by the newly organized 6th (Irish) Division under Major General George Bell. Unlike the veteran 3rd Division which had seen extensive fighting in the Ottoman Empire, the 6th Division had been raised only months prior, mostly from Irishmen who had enthusiastically joined the Army following the passage of the Irish Dominion Act of 1856. As such it was a thoroughly green unit, one that would require weeks of drilling to reach a satisfactory fighting proficiency, while also giving them some time to help them acclimate to the hot Indian climate. Even still, their added numbers were a welcome sight for the beleaguered British forces in India. Most importantly, they were fully equipped with the Pattern 1852 Enfield Rifle providing them with an incredible advantage over their more experienced Indian adversaries.

By mid-October, both the 3rd and 6th Divisions were ready to march and departed Sindh for the Punjab. The two divisions would travel up the Indus river for much of the next two months before finally arriving at the city of Ludhiana where they would meet with General Patrick Grants and his remaining East India Company forces in early December. Despite his station as acting Commander in Chief of India, Grant would immediately cede overall control of his “Army” to General England, owing to the latter’s seniority and superior rank as well as his exemplary service in Rumelia. Bell would similarly agree with Grant’s decision and submitted himself to the Canadian who was promptly placed in command of the three units, with the disparate East India Company (EIC) regiments being formed into an ad hoc Division under Grant (the 7th).[1] All told, the forces England commanded numbered around 42,000 men when it departed for Delhi in mid-December.

Under the milder December sun, the British Army made good time marching eastward, reaching the important fortress of Kunjpura on the 21st of December and quickly put the rebel redoubt under siege. However, their approach had not gone unnoticed by the Rebel leaders in Delhi who had busied themselves establishing their authority across Northern India over the last few months. Proclaiming themselves to be the rightful Government of a free and united India, the Mughal Government in Delhi minted coins bearing the facade of Sultan Muhammad Zahir Ud-din (Mirza Mughal). Laws were being issued in his name, taxes and tariffs were being collected across his domains in the North Western Provinces, and his consuls were forging diplomatic relations with all the enemies of Westminster. Moreover, the Delhi Government had organized a massive army of former Bengal Sepoys, Nawab levies, and Mughal Ahadis numbering some 114,000 men under the command of Mirza Mughal’s younger brother, Prince Mirza Khizr Sultan which was now advancing on the British column.[2]

Lieutenant General Richard England, Commander in Chief of all British Forces in India

Unlike his older brother, Mirza Khizr did have a talent for military command as he methodically drove the British and their Sikh allies back into the Punjab over the course of the Summer. Given this chance to finally destroy the British presence in the North, Mirza Khizr eagerly accepted this new task and attracted a great host to confront the foreign interlopers. Naturally, such a lumbering mass of men was quickly discovered by British scouts, however, who quickly informed General England of their approach. Undeterred, the British commander would elect to leave a regiment of Sikhs behind to screen the citadel of Kunjpura, whilst he took the remainder of his forces southward to prepare for the Mughal Prince’s arrival. Traveling a day’s march southward, he would eventually settle on a jagged plain located between the Yamuna river (specifically the Western Yamuna Canal) and the town of Panipat.

The Indian Army of Mirza Khizr would arrive later that evening, forcing a tense standoff between the now entrenched British and the massive Mughal Army. For the better part a week, the two forces would jockey for position along the eastern edges of the historic town. Each day, the two forces would array themselves on the old battlefield, sending forth their skirmishers and cavalry to harass the other resulting in minor clashes between the two. Yet neither side committed fully to a decisive engagement. General England’s decision to delay was a sound one as his force was vastly outnumbered, with half his troops being little more than raw recruits untested in the rigors of battle. Although he trusted the superior training of his troops and the superior quality of their weaponry, he realized that an offensive against such a massive force was foolhardy given the circumstances. Instead, England hoped to provoke an attack by the Indians and thus took up a defensive stance between Panipat and the Yamuna River.

For his part, Mirza Khizr was also reluctant to attack as he fully recognized the strong position of his British adversaries which was made stronger by a series of trenches and wooden stakes protecting their front. Moreover, his army, whilst incredibly large, was comprised mostly of poorly equipped Ahsam infantry or undisciplined levies loyal to their individual magnate. In effect, these men were little more than cannon fodder. The Sepoys he brought with him were certainly more potent fighters, but they comprised a minority of his force at Panipat. His artillery certainly outnumbered the British artillery corps, but the Indians had tended towards lighter field guns as opposed to the more powerful siege guns utilized by the British. Finally, his biggest advantage over the British was in cavalry, with the Mughal prince fielding nearly 20,000 horsemen; yet the British earthworks made them nigh unusable at Panipat. As such, an alternative course of action was needed if the Indians were to attack, however, after 5 days of this charade, cracks had begun to emerge within the Indian Army.

Although Mirza Khizr was the nominal commander of the Indian Army, his authority was not universally accepted, nor was it unchallenged by those within his ranks. In the eyes of many Rajas, Nawabs, Zamindars, and Mansabdars; their Emperor, Mirza Mughal was simply a figure head, a puppet who served at their pleasure, nothing more. His brother, Mirza Khizr was no different in many of their eyes; they were the real leaders of the Army, or so they deluded themselves into believing. His hesitancy to attack the British at Panipat only confirmed their biases to the point they paid him little mind and would slowly begin defying him more and more as the days progressed.

The 68-Pounder Lancaster Siege Gun

On the morning of December 28th, the two sides formed up as they had for the previous five days. The two sides unleashed their skirmishers to harry their adversaries as they had for the last week, all the while their artillery fired upon one another. Yet when the British withdrew back to their lines, several Mansabdars within the Indian Army broke ranks and gave chase. Soon more and more units began joining the impromptu attack seeking glory and riches from the outnumbered and, apparently, cowardly British. Riding to the fore, Mirza Khizr would attempt to dissuade his countrymen from making their foolhardy assault, only to be rebuffed by the haughty aristocrats and potentates he had surrounded himself with. Try as he might to reel in his disparate forces, Mirza Khizr could do nothing but watch as his Army advanced on the British line. With no other choice, the Mughal Prince ordered his remaining forces to join the assault; the Fourth Battle of Panipat had begun.

What followed would be a complete disaster for the Indians as the massive scale of the disorganized attack only meant that there were more bodies for the British troopers to shoot at. Firing 4 rounds a minute from 900 yards, the Indians were heavily bloodied before they could even reach their own firing range. Meanwhile, the heavier caliber cannons of the British tore gaping holes in the thick Indian ranks, killing or maiming scores of men with a single shot. The carnage was so great that by midafternoon, the battlefield was already strewn with corpses, most of which were Indians, which their comrades had to climb over to reach the British line. Only when Mirza Khizr’s forces finally arrived to reinforce their cohorts, did the Indian attack begin making any discernable progress against the British line.

Forcing their way to the front, the Mughal troopers and Sepoys would attempt to close the distance with the British and bring their strength in numbers to bare upon their adversary. Most failed to reach the British line owing to the faster firing rate and greater range of the Enfield, but as ammunition began to dwindle and exhaustion began to build more and more started reaching the thin Red line. It was here that the fighting became the most contested as the bloodied Indians threw themselves upon their tormentors ripping and tearing until their enemy was dead or they were themselves struck down. Faced with wave after wave of frenzied Indian infantry, the inexperienced Irish Division and Sikh Regiments began wavering under the sheer weight of Mirza Khizr’s attack.

However, the Mughal Prince’s success would be short lived as General England ordered his crack 3rd Division forward against the surging Indians. The veteran British riflemen moved to the front - replacing the battered, but still unbroken front line, before unleashing one devastating volley after another upon the approaching Sepoys and Ahadis. Many were slain where they stood, whilst a few would charge this new British line and spark a bitter melee including Prince Mirza Khizr himself who had leapt from his horse and joined the attack in person to rally his flagging troops. However, in the midst of the fighting, the Mughal Princeling was shot through the side of his skull, killing him instantly.

With Mirza Khizr’s death, any remaining cohesion in the Indian Army was immediately lost as the Indians devolved into a mass of humanity without clear order or leadership. Seizing upon this moment, General England order his men forward, with Bayonets fixed, whilst his Sikh cavalrymen were unleashed to cut down any and all they found. At that, the morale of the Indians collapsed, panic set in, and a general rout ensued as men fled for their lives. The hitherto unused Indian cavalry simply deserted the field leaving the infantry to fend for themselves. Overall, nearly 23,000 Indian troops would be killed that day, with more than half being slain in the ensuing pursuit. Another 11,000 would be wounded and more than 6,000 would be captured. The British in contrast only suffered around 4,000 casualties with most coming from the Irish Division and EIC regiments. The Battle of Panipat was a huge success for the British, opening the road to Delhi and put a nice cap on an otherwise very dreadful year.

The Last Stand of Mirza Khizr (Scene from the Battle of Panipat)

Sadly, for Westminster, news of this victory and the events that followed would not reach Europe until well after the start of the Paris Peace Conference at which point little could be done to change that event’s proceedings. However, the British victory at Panipat would have massive ramifications in Delhi as the Indian leadership effectively collapsed into infighting after such a devastating defeat. The Nawabs and Zamindars of the Mughal court blamed the relatively unscathed Sepoys for the disaster at Panipat, whilst the Sepoy commanders lambasted the arrogant and foolhardy Mansabdars for forcing such an unfavorable battle in the first place. In the coming weeks, the feud between the two would only worsen as the Sepoys were abandoned or misguided by their “allies”, not only resulting in the high attrition of Sepoy veterans, but also a systematic breakdown in cooperation between the two co-belligerents. In retaliation, many Sepoy commanders refused to support the Nawabs in their own foolhardy attacks, nor would they help defend their lavish estates from British raiders. Even the Mughal Emperor, Sultan Muhammad Zahir Ud-din (Mirza Mughal) was not immune from this feuding.

Although the Mughal Empeeror was still a highly respected man who could use his great influence to arbitrate disputes between his subjects, he was still just a man. A man who owed his crown to the landholders and aristocrats who had enabled his usurpation of the throne over his still very much alive father. As such, he often arbitrated in favor of the Nawabs, Rajas, and Zamindars who had put him on the throne. Naturally, this put him at increasing odds with the Sepoys and lay people of his “Indian Empire” who quickly became disenchanted with their new Emperor. Moreover, the Mirza Mughal’s efforts to move beyond his supposed puppet emperor status and establish his own government were also met with staunch resistance from both his aristocratic supporters and the common people of Northern India.

The state of anarchy that had existed during the opening months of the Rebellion had gradually been replaced by a return to normalcy. Only, instead of the British East India Company, the Mughal Court in Delhi attempted to surmount the sprawling mess of Princedoms and Noble Estates that dotted the Subcontinent. Some complied and humbled themselves before the Mughal Emperor, but most only offered lip service to Delhi. Mirza Mughal’s efforts to enforce any sort of taxation or economic policies across his domain were also rife with controversy as the magnates who had supported his rise to power paid little if anything in the way of taxes to the Delhi Government, whilst the common people were burdened with incredibly high tax rates. Moreover, his continuance of many of the East India company’s administrative policies made it abundantly clear that little would change for the commoners of India should the Rebels win the war against Britain.

Worse still, the Rebel forces in Delhi were plagued by a chronic shortage of munitions. Prior to the Rebellion, the British had supplied most of the weaponry, ammunition, and powder for the Sepoy Regiments, regiments who were now in opposition to their former suppliers. Their early victories against the British would manage to sate their need for more munitions as plundered stockpiles would restock their spent powder and ammunition for a few months. But with the British stopping their advance and now beginning to push it back, this state of affairs was no longer viable. By January 1857, many Indians began opening foundries and smithies to supply the Army, however, the rushed production of these weapons often meant that they were of lower quality than that of their British counterparts. Moreover, they could not match the power and range of the British weaponry, which easily outclassed anything the Indians produced.

These issues would only benefit the British in the days and weeks to come as they rapidly advanced on Delhi in mid-January, subduing many of its environs and retaking the Badli-ki-Serai west of Delhi by the end of the month. Several days later, they would force their way atop the Northern Delhi ridge overlooking the city, coming within a scant 2 miles of Delhi’s walls. By the 19th of February, their mighty siege guns were implanted atop the heights surrounding Delhi and began pounding away at the city’s medieval walls with brutal force. To combat this, Mirza Mughal would order his last leading commander, General Ghosh Muhammad to move against the British with his army.

Ghosh Muhammad complied, but in the ensuing Battle of Delhi he was undermined by the Nawab of Banda, Ali Bahadur who disregarded the veteran officer’s orders and foolishly launched his own, ill-advised assault upon the British position with his 4,200 troops. In doing so, he opened a great hole in the Indian line, an opening which was quickly exploited when the British blunted the impromptu Indian attack and launched their own counterattack. Overcome by the superior firepower and discipline of the British veterans, the Banda troopers were swiftly driven from the Battlefield, leaving a massive hole in the Indian line. Ghosh Muhammad would attempt to consolidate his disparate forces and fill the opening, but it was too late as the momentum of the British charge carried it into the thinned Indian line, shattering it within seconds.

With defeat now inevitable, Ghosh Muhammad ordered his remaining men to make a fighting retreat from the battlefield, which they accomplished at great cost. Of the 40,000 Indians who had fought that day, nearly half were lost to Delhi, most of whom were captured or simply deserted. The British would sustain several thousand casualties themselves, but seeing that Delhi was ripe with panic after the defeat of Ghosh Muhammad; the exhausted Britons would push themselves onward to the gates of the Imperial City and make an attempt upon its fabled walls. This attempt would fail, but it would succeed in other ways as the Mughal Emperor and many of his retainers would lose their nerve and flee the capital later that night.

British soldiers attacking the walls of Delhi

The news of Mirza Mughal’s flight destroyed whatever morale remained for the Indian troops within Delhi and when the British made a second assault the following morning, they easily brushed aside the remaining defenders, pushing their way atop the walls of Delhi. Soon after, the City’s northern gates were flung open, and the British troops poured into the city like a tidal wave crashing upon the beach. At this point Indian resistance within Delhi quickly collapsed, apart from a few pockets of continued resistance by several Sepoys. By noon on the 28th of February, the city was effectively in British hands, however, the submission of Delhi would not end the violence, in fact it had only just begun. Despite its admittedly meager resistance, an example still needed to be made of the city and people who had massacred 500 defenseless Britons – and their loyal Indian followers - in cold blood.

All Rebel Sepoys found within the city were immediately deemed traitors and executed without trial. Those who were lucky were killed instantly, usually by firing squad or were tied to cannons. Many of the officers and Subedars (sergeants) would suffer far worse deaths. Many were forced to eat cow or pig, others were subjected to gruesome torture, but eventually they were all killed and usually in horrible ways. Similarly, any Nawabs, Zamindars, Sardars, or other aristocrats known to have supported the Rebellion were executed, with many being hung from gallows or bayoneted until dead. Believing that justice had been served with these punitive acts, General England decamped from the city to meet with Lord Dalhousie and Lord Lawrence to discuss strategy. However, whilst this bloodletting would sate the desires of the Queen's troops, it was far from enough for the Company men, whose friends and families had been slaughtered back in May.

Taking advantage of General England's absence, many EIC soldiers and their Sikh allies toured the defenseless city, assaulting the men and harassing the women. When they received little condemnation for their actions from General England and his staff - who were busy readying the campaign against the Rebellious Princely States, they naturally progressed to far more heinous acts of violence against the people of Delhi. Added to this was a fair degree of plundered liquor and a lack of officers, many of whom had been killed in the recent fighting. First they would target the city's menfolk who were butchered like the animals they believed them to be. The women of Delhi were also victims of this cruelty, with many being subjected to terrible acts of sexual assault and rape. Even the children were not spared from the violence as young babes were cast from the city's walls, whilst those old enough to work were shot in the streets or bayoneted. Anything of value was stripped from the city, all its gold was confiscated, and its jewels were plundered. Any art of note was carted away, whilst the statues and buildings were torn down. The only buildings spared any desecration were the Emperor’s palace within the Red Fort and the lone church within Delhi, the Central Baptist Church.

The Execution of Traitorous Sepoys

When five days of this grisly spectacle had passed, General England finally returned to the city where he discovered to his horror the devastation his troops had wrought. Sadly, little would come of this butchery as the instigators of these massacres were insulated by their commanders who blamed the matter on an uprising that never actually occurred. General England and his lieutenants were not immune from controversy either as his need for men and innate biases against the Indians may have persuaded him to look the other way regarding this incident. Either way, the end result is the same, as Delhi was now hollowed out.

The total extent of the massacre is unknown, but modern estimates put it between 20,000 and 50,000 deaths from the battle and ensuing massacres. Thankfully, much of the city’s population had fled the city before the brutal sacking, sparing most of the city’s population from the slaughter. Sadly, an unknown number of these survivors would die from exposure to the elements or hunger in the coming days and weeks as their homes and livelihoods had been ruined by the vengeful British. Another important loss to Delhi was the art, treasure and riches which were looted from the city by Prize agents in the Company’s employ in the days and weeks following the Siege. The pilfering was so great that there was little difference between the great princes of Delhi and a beggar in the days following the city’s sacking. Sadly, for the British, the Recapture of Delhi would not bring about the outcome they desired.

Rather than demoralize the Indian Rebels and convince them to surrender; the brutal sacking Delhi and the massacre of its people galvanized the Rebels to even greater levels of resistance. In their eyes, surrender now meant almost certain death and their only chance at survival was complete victory over the British. Moreover, the flight of Mirza Mughal and his handlers would provide some measure of legitimacy to the remaining Nawabs and Zamindars still in revolt against the British. His continued defiance would also inspire other Indian patriots to take up arms and continue the fight against the foreign interlopers. Most importantly, one of the strongest and most populous states in India – the Kingdom of Awadh - was still in a state of revolt against British hegemony in India.

The Princely State of Awadh was a prominent state in the North of the Indian Subcontinent located between the Doab of Delhi and the lands of Bihar. Although it was a relatively young state compared to the mighty Mughal Empire or Maratha Confederacy, the Awadh state was still quite potent, both in wealth and military power. Owing in large part to its strategic position along the Yamuna and Ganges Rivers, Awadh was densely populated and incredibly rich both in trade and commerce.[3] That is until the British Empire began imposing its will upon the Kingdom, stripping away its Eastern provinces and forced into increasingly unfair economic treaties. By 1801, it was effectively reduced to vassalage by the British who appointed and removed its kings on a whim. Such an event would have happened again in late February 1856, had the rebellion at Agra and the attack on Delhi not taken place as a British Army had been dispatched to replace the allegedly incompetent Awadhi King, Wajid Ali Shah.

Wajid Ali Shah, King (Nawab) of Awadh

Instead, news of the Rebellion at Agra compelled Wajid Ali Shah to join the nascent Rebellion, lending his not inconsiderable support to the cause of an independent India. The British Resident in Lucknow, General James Outram was quickly imprisoned; whilst his would be jailors (the British soldiers of the 32nd Regiment of Foot) were quickly overwhelmed by traitorous Sepoys and Awadhi forces near the town of Faizabad. These events were followed soon after by several uprisings at Daryabad, Salon, Sitapur and Sultanpur, effectively eroding British influence over Awadh within a matter of days. Most Britons in Awadhi territory were either slain or imprisoned, with only a small handful holding out until they were finally relieved by the Nepalese Gorkhas in mid-April. Despite this blistering opening salvo in Awadh, this front would only see sporadic fighting for the remainder of the year as the East India Company and British Government rightfully focused their attention and resources on the re-subjugation of Delhi and its environs.

During that time, the Nawab of Awadh worked tirelessly to reestablish his dominion over his forefather’s country, extending his influence from the Yamuna River to the border with Nepal, and the region of Rohtas to the lands of Mainpuri. He quickly subordinated the nearby Sepoy Regiments, bringing his nominal military strength up to an impressive 27 regiments of infantry and 4 of cavalry. Beyond this he levied another 100,000 soldiers of varying quality and skill. He would establish weapons foundries in Lucknow, producing dozens of cannons and thousands of muskets for his troops. Despite these extensive military preparations, Wajid Ali Shah’s efforts to expand the Indian Rebellion into Bihar, Bengal and Central India met with failure, yet his campaigns against the Rohillas of Rampur met with more success as the latter were forced back to their walled city.

One Awadhi commander of particular note during this time was the Peshwa of the now defunct Maratha Empire, Nana Saheb. A charismatic leader and a talented commander, Nana Saheb would prove instrumental in reducing a number of British holdouts across the Gangetic plain over the Spring and Summer of 1856, massacring British soldiers and civilians at Kanpur, Safipur, and Bilgram. Although his direct involvement in these incidents is disputed, he was still present at many of these events and it was his followers who committed these acts, earning him the undying hatred of the East India Company leadership. As the year progressed and his success continued, Saheb’s following continued to grow from 1500 die hard followers in March 1856 to nearly 9,000 light cavalrymen in the Maratha style by the start of 1857.

By the Spring of 1857, however, the situation had changed completely for the Indians. Delhi had fallen to the British and Mirza Mughal had fled to Lucknow seeking aid from his strongest vassal. Naturally, this earned the ire of the British, who focused in on the Awadhi State with greater intensity than before. Even still, the British did not move against the Awadh state directly, choosing instead to target the smaller Principalities on its periphery first. In early March, the 6th “Irish” Division would fight its way southward against the rebellious cities of Gwalior and Jhansi, which were both recaptured after a three-month long campaign. As this was taking place, the 7th Division under General Grant would make its way to the north of Awadh and join with the Gurkhas of Nepal, where together, they would relieve their Rohilla allies at Rampur. The main strike, however, would come in mid-April as General England and the 3rd Division would finally begin their advance down the Ganges towards the Awadhi capital of Lucknow.

Nana Saheb, (Claimant) Peshwa of the Maratha Empire

Recognizing that the British forces were now divided along many separate fronts, Nana Saheb would elect to move westward against General England’s force with the majority of the massive Awadhi Army. The remainder of the Awadhi forces would be sent to reinforce their positions in Bihar, Jharkhand, and Bundelkhand against the advancing British. Setting out with around 80,000 troops, Nana Saheb hoped to destroy England’s division then swiftly turn against each of the others, which he hoped to defeat in detail. Despite its lumbering size, the Indian Army would manage to surprise the much smaller British force near the town of Etawah. The ensuing battle would be rather short as the British forces were divided along the Yamuna River. Those on the Eastern bank were quickly forced to retreat, whilst those on the far bank watched in horror as their comrades were cut down en mass as they fled. Nana Saheb’s attempts against the remainder of the British 3rd Division on the Western bank of the Yamuna would be met with more difficulty, however as they vehemently guarded the nearby river crossings until nightfall, at which point General England ordered his remaining forces to retreat. Overall, the battle of Etawah was a solid victory for the Indians, but not a decisive one as General England’s force, whilst thoroughly beaten and bloodied, still remained as a cohesive unit. Moreover, with the other fronts under pressure from the British, Saheb could not chase down the fleeing 3rd Division for long, eventually ceasing his pursuit four days later.

Turning his attention northward, Saheb would move against General Grant and his 7th Division in mid-May, meeting them and the Nepalese Army near the town of Bareilly. Unlike at Etawah, the battle of Bareilly would be more evenly matched, with the British maintaining a strong defensive position around the town. The Nepalese Gurkhas also proved themselves to be especially potent fighters as they killed scores of the lightly armed Awadhi troops whilst suffering few losses themselves. However, when Nana Saheb's light cavalry appeared to their rear, the British were forced to cut their losses and withdraw northward into the hills of Nepal. In terms of casualties, the Indians fared much worse at Bareilly than they did at Etawah, losing around 5,800 troops to 3,100 British casualties. Worse still, the British force had escaped intact yet again, once more depriving Nana Saheb of his crushing victory.

Despite suffering a pair of bitter losses, the British would quickly regroup and re-consolidate their forces in early June. When the Awadhi Army encountered General England at the city of Etah, the British boasted two divisions (the 3rd and 6th) as well as four Gurkha infantry Regiments and half dozen Rohilla and Sikh Cavalry Regiments. The Battle of Etah would prove to be rather indecisive for either side, for whilst the Indians held the field at the end of the day, they had suffered for it greatly, losing nearly 14,000 troops in the engagement. Furthermore, with the arrival of the British 2nd Division under Major General John Pennefather at Calcutta in early May, the British could now put pressure on the Awadh state’s eastern borders whilst their armies were away in the West. The arrival of the 2nd at Calcutta would be followed one month later by the 5th in early June and the German contingent of the British Foreign Legion in late August, boosting the number of British troops in India to well over 80,000 troops and 6 divisions by the beginning of Fall.

Even the onset of the hot and humid Indian Summer would not provide much aid for the besieged Indians, as the British renewed their offensive against the Awadh state with almost reckless abandon. Over the course of twelve days in early July, General England would embark on his famous Doab Campaign forcing Nana Saheb and his troops into a number of clashes. Although some of these battles would result in Indian victories, the British General refused to withdraw and continued to press the Awadhi commander where ever he could. Eventually, on the 15th of July, the two forces would meet near Nana Saheb's estates by the town of Kanpur. Although the Indians held a strong defensive position nestled in between the city and the Ganges River, they were in a ragged state. Their weaponry was in an utterly abysmal condition after months of constant campaigning, whilst their morale had completely collapsed once news arrived from Paris signifying the end of the Great Russian War. Moreover, the British Army's size had nearly doubled with the arrival of General Grant's division and another 10 Gurkha regiments, bringing the two forces to a more equal footing.

The battle would begin well enough for Nana Saheb as his troops fended off an assault by the British Irish Division and another by the Sikhs, but when his horse was shot out from under him, his troops quickly lost heart and fled the field of battle barely an hour and a half after it began. Many Awadhi soldiers would flee to the nearby town of Kanpur, where they would make a desperate last stand with the city’s garrison. Most, however fled into the Ganges River, hoping to swim across to the other side. The British seeking to destroy the Awadhi Army once and for all, chased them down into the waters and began brutalizing any rebel they could get their hands on. The massacre that followed was so great that the waters of the sacred river turned red with the blood of nearly ten thousand Indian soldiers.

Sadly, the disaster at Kanpur was not over for the Indians as the Maratha Peshwa Nana Saheb had survived his fall only to have his horse fall upon him shattering his pelvis and breaking his legs. Recognizing that the battle was lost, several of his guardsmen quickly threw him on a horse and escorted him from the field only to be discovered by several British troopers who immediately set off in pursuit. Injured as he was, Nana Saheb could not escape his pursuers and was soon cornered outside his own estates, his only allies remaining being a handful of his most dedicated followers. Trapped, the British commander, one Brigadier John Nicholson offered to spare him and his compatriots if he surrendered; Saheb refused, prompting the British to attack. The fighting was brief but bitter as the Marathas fought to the death. Although accounts of Nana Saheb's death differ, the most popular was that he was stabbed through the heart by Nicholson, killing him instantly. The remainder of his company were soon cut down as well, bringing a decisive end to the Battle of Kanpur.

The death of Nana Saheb and the destruction of his army at Kanpur was a mortal blow to the Awadh State. Although the Awadhi would continue to resist for another few weeks the writing was on the wall and so in early August 1857, King Wajid Ali Shah dispatched emissaries to the British requesting terms. Whether this was a genuine offer at reconciliation with the British, a humanitarian effort to save the lives of his remaining subjects, or a craven attempt to save his own throne; none, but the Nawab of Awadh can say. Unfortunately for all, the British would refuse to negotiate. Instead, they demanded the immediate release of the British consul General Outram and any other British prisoners in Awadhi custody. They also demanded an indemnity for all slain Britons, amounting to a sum of 20 million Rupees. Wajid Ali was also required to abdicate his throne and cede all his territories to the British. Finally, the British demanded the surrender of Mirza Mughal - who was known to have fled to Awadh and most damning of all, the surrender of any and all Sepoys within his domain who had taken up arms against the British and their allies.

The Pursuit of Nana Saheb

Despite the harshness of these terms, records suggest that Wajid Ali Shah had strongly considered accepting the British demands as news of the Treaty of Paris had recently reached Lucknow, greatly demoralizing the Awadhi court. No aid would be forthcoming from the Qajaris or the Russians, effectively dooming the Indian Rebellion. At this point, further resistance would only mean further suffering and bloodshed. Awadh was rich enough to pay the British their blood money, and the cessation of Awadhi territory would effectively be reverting back to the pre-war antebellum, only to a greater extent. However, the last term, added at the behest of Lord Dalhousie and Lord Lawrence, was simply too much.

Honor dictated that Wajid Ali Shah protect his sovereign and guest, Mirza Mughal against any adversary seeking him harm. Beyond this, there was also the fate of the Sepoys within his realm. Knowing how the Sepoys at Delhi had fared when captured by the British, such a demand for their surrender would almost certainly bring about their deaths. Unwilling to condemn many thousands of good men to the gallows just to save his skin, Wajid Ali Shah unilaterally broke off negotiations with the British and prepared his kingdom for a fight to the death.

Sadly, for the Awadhi, the end result of this conflict was never in doubt as the Indian Army had been destroyed at Kanpur, its military leadership had been decapitated, and its morale gutted. The campaign that followed would see the British besiege one city after another, sacking each and decimating their ability to make war. This was to be a total war, the first of its kind with little regard given to the distinctions between soldier and civilian. Awadhi roads were torn up, weapons foundries were leveled, and their rivers dammed. Farms and fields were pillaged of their yields then burnt and sown with salt. Civilian property was looted or destroyed with little concern given to the needs of their owners. This wanton destruction was intentional so as to punish the rebellious Indians, to make them suffer for their treachery, their villainy, and their murderous barbarity. More than that though it was meant to encourage their surrender, to eliminate their ability to make war, and to erode their will to fight.

Efforts by the Awadhi to resist only worsened this, yet resist they did as many would choose to unite under Tantia Tope, a former deputy of Nana Saheb who had survived the Battle of Kanpur. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, Tope would continually attack the British, usually targeting their extensive supply lines throughout the remainder of the Summer and into early Fall. Despite his efforts, however, the British continued their relentless advance upon Lucknow, razing the Awadhi countryside as they went. By early October, they would finally arrive outside the city and prepared to besiege it as they had all the others in their path.

Yet it was not to be. Unwilling to see his beloved home destroyed, Wajid Ali Shah ordered the gates opened to the British and surrendered himself to them. For his part General England accepted the Awadhi King’s surrender and refused all demands from the EIC to sack the city or punish its inhabitants. There had been enough blood shed for this gruesome campaign, and he would have no more of it on his conscious.

Mirza Mughal in contrast would attempt to flee from the British once more, however, he was soon discovered and captured by the British who promptly sent him to Britain in chains where he would live out his days in a gilded cage.The Surrender of Awadh and the capture of Mirza Mughal would effectively signal the end of the Indian Rebellion. Although some Rebel leaders like Tantia Tope would continue to resist well into 1858 and 1859, their aspirations of victory were ultimately dashed with Lucknow’s surrender to the British. By 1860, any remaining rebels hidden across the Indian countryside put down their weapons and surrendered to the British, following the issuance of a general amnesty by the British Government, an act that formally concluded the Indian Rebellion of 1856.

The British had won, but the costs had been great. In terms of lives lost the British had lost upwards of 27,000 men, women, and children to the Rebellion between the Mutiny at Agra in February 1856 and the last recorded skirmish near Dhanbad in March 1860. The toll on the Indian population would be much worse, with around 187,000 soldiers and civilians being killed by the British and their allies in various battle or massacres over the course of the conflict. However, many hundreds of thousands more would die in the ensuing famines and pandemics that swept the countryside, with upwards of 1.5 to 2 million people dying between the end of 1855 and the beginning of 1860. Additionally, the British Government had spent an enormous 50 million Pounds Sterling subduing the Rebellion, which in addition to the exorbitant costs of the Russian War, heavily strained Westminster's treasury.

Another indicator of the Rebellion’s cost, however, would be in its annual revenues to the United Kingdom's coffers. In 1855, the year before the Revolt, the Subcontinent contributed 28 million Pounds Sterling in loan interest payments, and another 35 million Pounds in exported commodities and trade goods. In 1859, one year after the war’s official end, nearly a third of that sum had been lost and would take nearly twenty years to reach the same levels as before the Rebellion. Overall, the Indian Rebellion of 1856 to 1858 was one of the worse tragedies to befall the Indian subcontinent since the Mughal Conquests in the 16th Century. The subcontinent was ravaged across the Ganges plain, cities were razed to the ground by the vengeful Brits, and the once prosperous Awadhi countryside was burned to cinder and ash. Although the Jewel of the British Empire had been reclaimed, it was tarnished and stained with the blood of its people.

Next Time: The Long Road Home

[1] Technically, Richard England was born in what is now Detroit, Michigan, but at the time it was considered a part of Canada. It wouldn’t be until 1796 when Detroit was officially ceded to the United States.

[2] The Ahadis were the household troops of the Mughal Emperor. By the 1850’s, they were mostly a ceremonial role and had been reduced to almost nothing. Here, the extended success of the Rebellion in Delhi prompted a restoration/expansion of the unit, although they are still not as proficient or numerous as they once were.

[3] For Reference, in 1764 the Awadh State managed to pay off a 5 million Rupee indemnity to the British in a single year without much trouble. Later on, Awadh would be forced to accept British mercenaries and advisors for a annual fee of 50 Lakh (roughly equivalent to 5 million Rupees) starting in 1773 and later rising to 70 Lakh (7 million Rupees per year in 1798. During the 1820’s the Nawab of Awadh, Ghazi al-Din Haydar donated 10 million rupees (roughly equivalent to 1 million Pounds at the time) to the East India Company to help relieve the economic crisis in Burma. Even by the 1850’s Awadh was still a great breadbasket for India and a thriving population center, whilst Wajid Ali Shah was a great patron of the arts and sciences whilst King of Awadh in OTL.

I am really sorry my post is regarded sophistry - a clever and false argument with the intention to deceive. I sincerely do not wish to deceive anyone.I think it's possible to simultaneously acknowledge the inherently oppressive nature of the nation-state while also condemning specific examples of that oppression without resorting to bothsidesism and other forms of sophistry.

My post was on the nature of a specific political entity, with examples that I do consider valid. And an entity that is definitely not nation-state.

You're absolutely right ! History is not black or white, it's always a shade of greyWell I could tell you, but where's the fun in that. Besides, I'll have the next chapter out tomorrow, so you'll find out soon enough anyway

I wouldn't say the British were "Evil" during the 19th Century; greedy - yes, hypocritical - definitely yes; self interested - yes again, but evil, I'd have to say no on this. If anything, the British were following realpolitik to the letter. The UK was the leading power of the world at that time and they did whatever they needed to keep it that way, so much so that they did some very heinous and hypocritical things to ensure they stayed on top. The OTL Crimean War and Opium Wars being prime examples of this.

That being said, they still did some measure of good for the world during this time, namely in combating the International Slave Trade and in sponsoring various scientific and medical advances that have saved or improved millions, if not billions of lives over the course of the last two centuries.

If all the world thought that way, we would be saved for a lot of stupidity !I would expand on it, that basically every state in history has committed atrocities. The Melian Dialogue is 2,500 old - not a colonial era text. The self-flagellation over the colonial era, as if states using force to obtain their interests was invented then, is ahistorical.

Maybe it was uncharitable on my part to insinuate that you were making a dishonest argument, so I apologize for that. It does still feel like nitpicking to bring up other random examples when people are talking about the actions of one specific empire. The nature of "evil" is really subjective and hard to quantify, but I think a line has to be drawn somewhere so people can criticize an historic event without getting the whole "well they weren't so bad by the standards of the time," etc. spiel.I am really sorry my post is regarded sophistry - a clever and false argument with the intention to deceive. I sincerely do not wish to deceive anyone.

My post was on the nature of a specific political entity, with examples that I do consider valid. And an entity that is definitely not nation-state.

They did it to save their rank, another country would have done it if Britain didn't. It's not an excuse, but the most stupid thing to do is to judge the behaviour of the past with 2021's eyes, 'cause you reach nothing but hate and divide with this !While certainly not the Nazis, there was no other Empire quite like the British, who left deep economic and psychological scars wherever they went, no other Empire quite so ruthlessly exploitative, no other Empire quite so free in its use of divide-and-rule politics, no other Empire quite so successful.

Ensuring their gain wherever they went, at any cost, without regard for anything else certainly makes them evil in my book. The actions of the British have touched nearly every country on the planet throughout history (mostly in a bad way). Few of their actions were by themselves as heinous as anything the Nazis did for example, but considering the sheer scale of their negative impact and for how long they did it, they cannot be considered a force for good.

The level of violence in your Indian Rebellion is shocking given that the OTL 1857 Revolt did not devolve to such an extent. Also, where are the many heroes of the OTL 1857 Revolt? Only Nana Saheb is mentioned here.

Look at Communist China in Africa for exempleSure but any other People with the same power and geopolitics as the uk would act the same if not worse

At least they are not murdering democratically elected leaders, like the American hypocrites did in LATAM.Look at Communist China in Africa for exemple

Last edited:

There were plenty of contemporary voices which criticized the actions of the British and all the other empires of the period on much the same basis that we do today. It's ahistorical to assume that everyone was just okay with imperialism and operated on a completely different moral spectrum.They did it to save their rank, another country would have done it if Britain didn't. It's not an excuse, but the most stupid thing to do is to judge the behaviour of the past with 2021's eyes, 'cause you reach nothing but hate and divide with this !

Trying to rate imperialist political entities as different levels of evil is a losing game in my opinion. And I mean imperialism in all senses, not just the European colonial sense. We can point at events and say these were “the worst” but everyone’s own background and experience colors what they think those event are.

The important thing is to recognize that such events are bad and do our best to avoid them in the future. Not that we argue over who is the absolute worst. All of their hands are dirty. Whose hands are the dirtiest isn’t the important thing in my opinion.

The important thing is to recognize that such events are bad and do our best to avoid them in the future. Not that we argue over who is the absolute worst. All of their hands are dirty. Whose hands are the dirtiest isn’t the important thing in my opinion.

Who cares if another empire might have also done it if they were placed in the same position of power or that they simply refined the tools of empire used in the past it doesn't make the aden emergency, The Chinese resettlement, The amritsar massacre, the partition of india, the famine in bengal, the Kenya concentration camps, the boer concentration camps, or their drug empire with china(which is on a whole another scale that I don't think anyone other empire in history done anything similar to or to that scale) I could go on, any less horrifying and grotesque. At the end of day we could argue in circle all day using whataboutism with the british empire or some other argument but it still doesn't excuse any of it, or change the fact that in the 19th century and large parts of the 20th they were the worst or one of the worst empires out there.

I get you. It is not nitpicking though:. I am no British, nor an AngloSaxon in general. On the contrary, I come from a nation parts of which have been british colonies. So, I don't have any soft spot for the British Empire. But at the same time I am a history enthousiast and I like reading about international relations. So when I see something that I consider a (very valid) responce that comes from the heart but it is not based in historical facts- and I immediately think of a number of examples that refute a statement, then I write an argument. And yeah, the biggest reason I wrote the post was because of the use of "evil". I don't get what benefit it does to expand our knowledge and understanding of history by claiming political entities as "evil". And I sincerely thought that the examples I presented were valid counter arguments. E.g. the standard policy of the Athenians on revolting subjects was to kill all the males and sell the women and children as slaves. If I start talking about the evil city-state of Athens how would it help in a 5th century timeline?Maybe it was uncharitable on my part to insinuate that you were making a dishonest argument, so I apologize for that. It does still feel like nitpicking to bring up other random examples when people are talking about the actions of one specific empire. The nature of "evil" is really subjective and hard to quantify, but I think a line has to be drawn somewhere so people can criticize an historic event without getting the whole "well they weren't so bad by the standards of the time," etc. spiel.

Bottomline, I assure you it was standard argumentation in a history thread and thank you for giving me the benefit of the doubt.

What I am indeed guilty of, is that I helped continuing derailing the thread. I apologize for that and I won't post anything else that is not related to mid-19th century events described by the author.

Last edited:

I'm working on it, I'm working on it, just give me a few more hours!Good ol' thread madness pre update, save us Earl Marshall!

No rush meant, just excited! (slinks back to eu4 quietly)I'm working on it, I'm working on it, just give me a few more hours!

Chapter 89: The Long Road Home

Author's note: Apologies for a shorter update than normal, but hopefully a faster upload rate will suffice. That said, I'll be covering these topics again in more detail in the chapters ahead.

Chapter 89: The Long Road Home

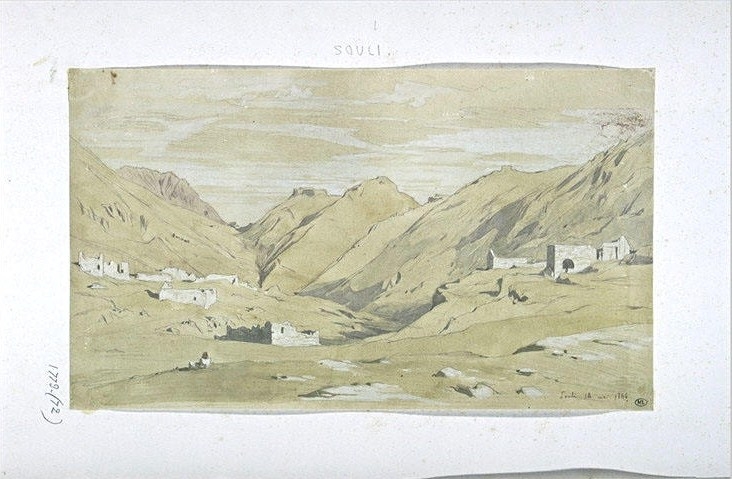

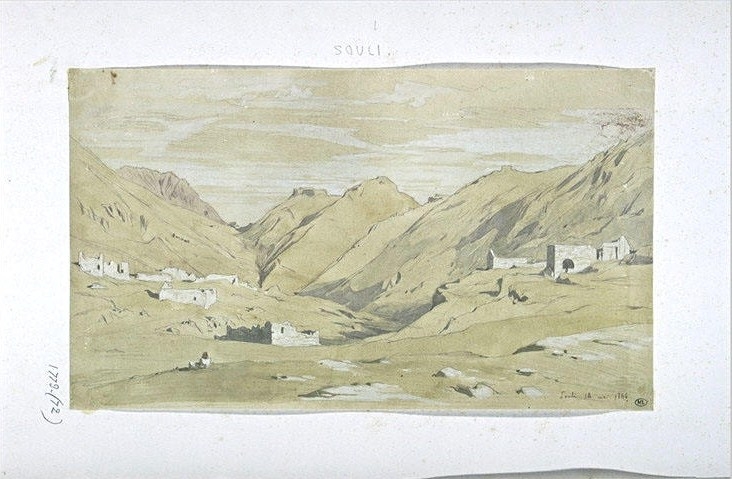

The Souli Valley circa 1857

The Spring of 1857 would greet the dusty little village of Dragani as it had every year before. The Sun was burning bright, the air was hot and dry, yet the breeze was gentle and cool. Children played in the streets from sun up to sun down, pretending they were some great heroes of old like Herakles and Achilles or Georgios Karaiskakis and Markos Botsaris. The shepherds were up in their hills tending to their flocks, whilst the farmers were out in their fields tending to their crops. The women gossiped about this or that, about far away events that had little impact on their lives, and the distant war along the Danube – a war that was now long over.

It took a considerable amount of time for news to reach this remote little backwater in rural Epirus, as few made the journey to this town. Yet on one particular day in early April, a stranger appeared. He was an old man in his late 60’s, one with a prominent mustache and long silver hair. He walked with a pronounced limp earned from a lifetime of battle and hardship, yet he stood proud and tall. He was blind in one eye, yet he did not need to see for he had known these roads his whole life. The hills and valleys, the olive trees and the orchards; they were all the same as his memories, distant memories of a childhood so long ago. He could never forget this place, for it was his home. It was a place he had fought long and hard to liberate for nearly 50 years of his life and now at the end of his days, it was finally free.

The people were strangers to him too, for his people, the people of his village had been chased into exile by the despot Ali Pasha of Ioannina more than fifty years ago. Those who settled here in the following years were not his kin, but rather Cham Albanians and Epirote Greeks who had little relation to him or his clan. They surely knew of him, or rather his now exaggerated exploits which claimed he had single handily defeated the Turkish hosts at holy Missolonghi on three occasions. That he had ridden to Nafplion in a single day and chartered the entire Greek constitution by himself. That he had slain the tyrant Reshid Pasha and driven the Egyptians into the sea, saving Hellas from the vile Turks.

Yet that hero of yore had long since disappeared from the world, retreating a small house on the edge of Agrinio after the war where he lived a quiet life of isolation. His only visitors being his children; the valiant soldier Dimitrios and the beautiful court lady Rosa who visited on occasion as their busy lives in the capital made visiting hard. Yet the news from Paris changed everything for this man as the 1857 Treaty of Paris not only confirmed the Tsar’s victory over the Sultan, but it also confirmed the annexation of Thessaly and Epirus to the Greek State. Throngs of jubilant people took to the streets all across Greece celebrating this momentous occasion, the young danced in the streets, whilst the old sang joyous songs and indulged in spirits until the wee hours of the night. Yet for the old Strategos of Agrinio, it marked the beginning of his long journey home. Bidding his family and friends farewell, Markos Botsaris left Agrinio for the Souli Valley, seeking his beloved homeland one last time.

Traveling as fast as his ragged 68-year old body could take him, Botsaris traveled first to the holy city of Missolonghi where he had spent so many years of his life fighting against the Turks in a desperate defense of his new home. From there, he would travel by boat to the bustling port city of Preveza and then onward to rugged Arta. From there, however, he traveled on foot, northward to the Souli Valley and the village of Dragani where he had spent his childhood so many years ago. Upon coming into sight of this place, old Botsaris broke down into tears for his life’s work had been accomplished, his homeland – his beloved Souli was free, and he was finally home. Weary as he was after such a long and toilsome journey, Markos Botsaris would find a quiet place upon a hill overlooking the town of his birth. Taking a seat beneath a small olive tree, with the whistling wind passing through his hair and the lavender sky looking over him Markos Botsaris would breathe his last with a smile on his face as he passed from this mortal coil into the realm of God.

Although accounts differ over the exact circumstances of Markos Botsaris’ death, it is known that he had returned to the Souli Valley prior to his passing. Such a journey was commonplace for many such survivors of the Revolution. Many had fled from their homes in Thessaly, Epirus, Macedonia, Thrace and Asia Minor during the War for Independence and now, some thirty years later they had a chance to return home. Of course, not all would go as most had established new lives for themselves within the old borders of Greece, yet some like Botsaris and many of his Souliotes kin would.

However, the lands they would find were in a state of flux as the Ottoman Empire had begun withdrawing from these provinces almost immediately after the signing of the earlier Treaty of Constantinople in mid-1855. First to leave were many of the first-rate Army regiments in the region which were reassigned to the Danubian Front against Russia. Despite this, many hundreds if not thousands of Ottoman troops remained in Thessaly and Epirus to keep the peace and maintain appearances if nothing else, at least until the Armistice with Russia in the November of 1856 at which point these last remaining Ottoman authorities in the province were slowly withdrawn as well. By April 1857, this process was essentially complete, and no sooner had they left than the Greek Army, and an army of Greek bureaucrats moved in.

The integration process that followed was rather smooth all things considered, although a handful of incidents would occur between the incoming Greeks and the outgoing Turks. One of the largest issues was the extent of Greece’s new borders. Owing to the vagaries of the Treaty of Constantinople and the Treaty of Paris (both of which declared the cessation of Yanya and Tirhala to the Kingdom of Greece, but not their extent), there existed some measure of debate over where exactly the border between them lay. Greece pushed for the northernmost extent of these territories, including the northern edges foothills of the Olympus mountain range and the entire Aoos River valley up to Vlore. The Ottoman Government naturally pushed for the southernmost boundary as a means of preserving its already damaged honor and legitimacy.

Tensions became so heated that war threatened to break out between Athens and Kostantîniyye. Thankfully, through the mediation of Britain and France, the two came to an agreement; Greece’s boundaries in Epirus would lie along the Aoos River to the south and east of Tepelene and then onto the Ionian Sea by the shortest, but most natural route so long as this route included the city of Himara. In Thessaly, it was agreed that the Ottomans would maintain control over the passes through the Olympus Range, whilst Greece would receive everything to the South of the mountains. Finally, the Kingdom of Greece would pay an indemnity of one million Pounds Sterling to the Ottoman Empire, resolving the dispute between them.

However, coinciding with this movement of Hellenes into Thessaly and Epirus was an even larger exodus of Turkish and Albanian notables who were unwilling to live under Greek rule. Property rights would be a major point of contention as returning Greek families often finding their ancestral lands occupied by new Turkish or Albanian settlers. On most occasions a diplomatic outcome was reached with one party or the other ceding their rights to the land or property in question, in return for a financial indemnity issued by the Greek Government. On more than one occasion, these disputes devolved into violent scuffles with a number of Greeks and Turks ending up dead. Most Turks simply left after a few weeks of this abuse and traveled northward for Ottoman territory.

Thankfully, the process of expanding Greece’s institutions into Thessaly and Epirus would prove more peaceful fortunately. The autocephalous Church of Greece would seamlessly assume jurisdiction over the new provinces of Thessaly, Epirus, the Ionian Islands, and the Dodecanese Islands, in return for financial compensation to the Ecumenical Patriarch. Similarly, the implementation of Greek Laws across the new lands was met with great approval by the Christian peoples of these regions, who were now equal before God and the Government. Many of the Muslim peoples still residing in these provinces would take umbrage at this, as they had enjoyed various legal privileges over their Christian neighbors thanks to the Ottoman Government’s usage of Sharia Law, which was largely ignored in Greek courts. As a result, many thousands more would depart for Turkey in the coming weeks and months.

While conflict with the Greeks, cultural differences and social pressure were certainly notable factors in compelling the flight of these Muslim populations, the deciding motive was more often and not, economic in nature. For the better part of the last two hundred years, the local economies of Thessaly and Epirus were dependant upon the major landlords of the region; the Chifliks who had acclumulated vast estates across the country. One such Chiflik, Ali Pasha of Ioannina became so powerful and wealthy, that nearly all of Greece and Albania were under his control. Yet, the manner in which these magnates gained their power was through the virtual enslavement of their tenants who were tied to the land they lived on and forced to work for a pittance.

Ali Pasha of Ioannina -

One of the most notorious Chifliks, who at his height controlled an expansive domain from Montenegro to the Peloponnese and from the Adriatic to the Aegean.

These men ruled their domains with an iron fist, who punished any resistance to their extortion with violence. Naturally, this heavy handedness resulted in various revolts over the years, but as these men were usually high ranking officials within the Ottoman Government, they could usually rely upon the support of the Ottoman Army to subdue any dissent. By the 1850's, however, this state of affairs was no longer possible.

With the War against Russia necessitating the withdrawal of the Ottoman field units from Thessaly and Epirus, these regions quickly erupted into anarchy. The Chifliks were forced to cower in fear as their former serfs marched through the fields and towns pillaging as they went. Many of these magnates prayed for the quick return of the Army to punish these haughty slaves, yet these prayers would fall on deaf ears as Ottoman authority in Thessaly and Epirus only continued to decline in the coming months. When it finally became known that the Sublime Porte was ceding the two provinces to Greece in late 1856, it was the last straw for many remaining Chifliks who promptly sold their properties to the highest bidder and fled north to the Ottoman Empire. Naturally, many of their attendants, retainers, administrators, guards, and suppliers were forced to follow as their livlihoods were based off servicing their masters.

Although both provinces would experience great reductions in their Muslim populations because of this, Thessaly would be hit the hardest with nearly the entire community had departed by the end of the year. By 1860, only a handful remained in Thessaly, most of whom lived in the cities and were usually of Greek or Albanian background. In Epirus, the situation was more complex as the Chifliks and their hangers on decamped for the Ottoman Empire en masse, yet unlike Thessaly, the Chifliks of Epirus had enslave their coreligionists with reckless abandon for no other reason than they were poor and unable to resist. When the Chifliks were chased out of Epirus, it was a combined effort by the Christian and Muslim peasants of the region, who had both suffered under their despotic rule.

Sadly, the flight of the Turkish and Albanian Chifliks did not bring about immediate relief for their former victims as many had dealt their lands to incoming Greek businessmen who had no qualms about continuing their predecessors vile practices. However, as slavery (and by effect Serfdom) was illegal in the Kingdom of Greece, these new Greek Chifliks were forced to provide some measure of wages to their laborers, yet in many cases it wasn't enough to survive. After several months of this, many farmers began reaching out to their representatives for help in resolving the issue. Ignorant of the true extent of the problem, many lawmakers in Athens extended minor financial assistance to these destitute farmers as they had done before in the 1830's and 1840s, and left the matter at that.

When this inevitably failed to resolve the issue, many simply left their fields altogether and marched on Athens demanding the Greek Government do more to finally resolve the issue. All told, some 11,800 peasant farmers would march on Athens, a sizeable number by any degree, let alone for little Greece. With throngs of angry people now upon their doorstep, the Greek Government had little choice, but to act on this issue once and for all. Despite resistance from various magnates and landowning lobbyists within the Legislature, the so called Farmer's March (I Poreia ton Agroton) would ultimately prompt the passage of the 1859 Land Reform Act.

Protests near the Royal Palace during the Farmer's March

First and foremost, the Greek Government reiterated its opposition to Slavery in all its forms and promised to pursue legal action against any entity known to have breached the law. Beyond this, the Athenian Government offered a one time buyback opportunity for any Chifliks or Greek landowners at 1.5 times the going rate per acre, effectively buying up massive swaths of land. All told, this would amount to nearly 14,000,000 Drachma being doled out to various magnates across the country, effectively ending their resistance to the measure.

The new laws would also work to prevent such a situation from ever developing again as small farmers (defined as any landowner with less than 50 acres) were formally barred from selling their property to another party for a period of five years. Similarly, to combat absentee landlordism, any landlord found to be absent from their properties for more than eight months in a year would forfeit their property to the Government, who would promptly auction off the vacant proprerty. Overall, the passage of the 1859 Land Reform Act would relief most of the pent up anger and frustration that these small farmers and laborers had held for generations. Nevertheless, some issues would sadly persist, but it was clear to all that this was a large step in the right direction.

Thankfully, the administrative integration of Thessaly and Epirus would go much smoother for the Greek government. As had happened with the Ionian and Dodecanese Islands before them, the Greek Government ordered a new census to record the populations of these provinces before declaring a new round of elections in the Fall. Although it would be the third election in as many years, the Athenian Government declared it necessary to ensure the people received their proper representation under the law. In the meantime, governors were appointed by King Leopold with Theodore Grivas serving as the Interim Governor of the newly constituted Province of Epirus (Ípiros) and Aristeidis Moraitinis for the Province of Thessaly (Thessalía). Similarly, each province would be allocated twenty interim representatives in the Legislature until a more accurate total could be determined following the census.

Theodore Grivas (Left) and Aristeidis Moraitinis (Right),

Interim Governors of Epirus (Ípiros) and Thessaly (Thessalía) respectively

Several months later in early September, the census was completed and the long-awaited numbers would reveal that the Kingdom of Greece had expanded to a massive population of over 2.2 million people. Around 91.5 percent were Hellenes or of Hellenic persuasion, 7 percent self-identified as Albanians, 1 percent were Turks, and the remainder were Germans, Poles, Italians, or Jews. The vast majority were Orthodox Christians, with only 3 percent following the Islamic faith, and 1 percent following Roman Catholic sect of Christianity or a Protestant denomination, with a smaller number of Jews and other religions. Overall, the new provinces of Thessaly, Epirus, the Dodecanese Islands, and the Ionian Islands had increased the population of Greece by just over 800,000 people. Of this total, around 270,000 people belong to the region of Thessaly, another 260,000 lived in Epirus, about 236,000 called the Ionian Islands home, and the remaining 60,000 living in the Dodecanese Islands.

Owing to this, it was decided to split the new provinces so that they would keep in line with the preexisting Nomoi of Greece and not provide any one province with too much political power. The region of Thessaly was therefore split into three separate provinces; that would become the Nomos of Larissa, the Nomos of Karditsa, and the Nomos of Magnesia with the latter taking the municipalities of Demetrias, Farsala, and Domokos from the neighboring Nomos of Phthiotis-Phocis. Similarly, the lands of Epirus would be divided up, with the Nomos of Arta expanding into the southern municipalities, whilst the new Nomoi of Ioannina and Argyrocastron divided the remaining territory between them. The Ionian Islands would also be divided into separate administrative units, with the islands of Kephalonia Ithaca, Lefkada being grouped together into the Nomos of Kephalonia, and the islands of Corfu and Zakynthos forming their own independent provinces. Lastly there was the Dodecanese Islands, which were left intact owing to their small size and even smaller population.

In terms of political representation, the Hellenic Legislature would be expanded to an impressive 217 seats with the Nomoi of Larissa, Ioannina, and Magnesia each receiving 10 representatives, the Nomoi of Corfu, Karditsa, Kephalonia, and Argyrocastron would each receive 9 representatives, whilst the Dodecanese and Zakynthos received 7 each. The political affiliation of these new representatives was almost entirely Nationalist in orientation, cementing their control over Greek politics for decades to come. However, this development would be both a blessing and a curse for the Nationalist Party as it eventually became divided over its ambitions, ultimately resulting in the fracturing of the party.

Yet that development was far in the future; in the present, the increased ranks of the Nationalist Party all but ended the political ambitions of Alexandros Mavrokordatos and his Liberal Party. While they did pick up 23 seats here and there, the addition of 57 new Nationalist politicians to the Legislature, completely eroded whatever negotiating power they still held as an opposition party. Any vote going forward could be secured on Nationalist votes alone with room to spare resulting in a very Nationalist oriented agenda by the Greek Government in the months and years ahead.

Next Time: The Lands and Peoples of Hellas

Chapter 89: The Long Road Home

The Souli Valley circa 1857

The Spring of 1857 would greet the dusty little village of Dragani as it had every year before. The Sun was burning bright, the air was hot and dry, yet the breeze was gentle and cool. Children played in the streets from sun up to sun down, pretending they were some great heroes of old like Herakles and Achilles or Georgios Karaiskakis and Markos Botsaris. The shepherds were up in their hills tending to their flocks, whilst the farmers were out in their fields tending to their crops. The women gossiped about this or that, about far away events that had little impact on their lives, and the distant war along the Danube – a war that was now long over.

It took a considerable amount of time for news to reach this remote little backwater in rural Epirus, as few made the journey to this town. Yet on one particular day in early April, a stranger appeared. He was an old man in his late 60’s, one with a prominent mustache and long silver hair. He walked with a pronounced limp earned from a lifetime of battle and hardship, yet he stood proud and tall. He was blind in one eye, yet he did not need to see for he had known these roads his whole life. The hills and valleys, the olive trees and the orchards; they were all the same as his memories, distant memories of a childhood so long ago. He could never forget this place, for it was his home. It was a place he had fought long and hard to liberate for nearly 50 years of his life and now at the end of his days, it was finally free.

The people were strangers to him too, for his people, the people of his village had been chased into exile by the despot Ali Pasha of Ioannina more than fifty years ago. Those who settled here in the following years were not his kin, but rather Cham Albanians and Epirote Greeks who had little relation to him or his clan. They surely knew of him, or rather his now exaggerated exploits which claimed he had single handily defeated the Turkish hosts at holy Missolonghi on three occasions. That he had ridden to Nafplion in a single day and chartered the entire Greek constitution by himself. That he had slain the tyrant Reshid Pasha and driven the Egyptians into the sea, saving Hellas from the vile Turks.