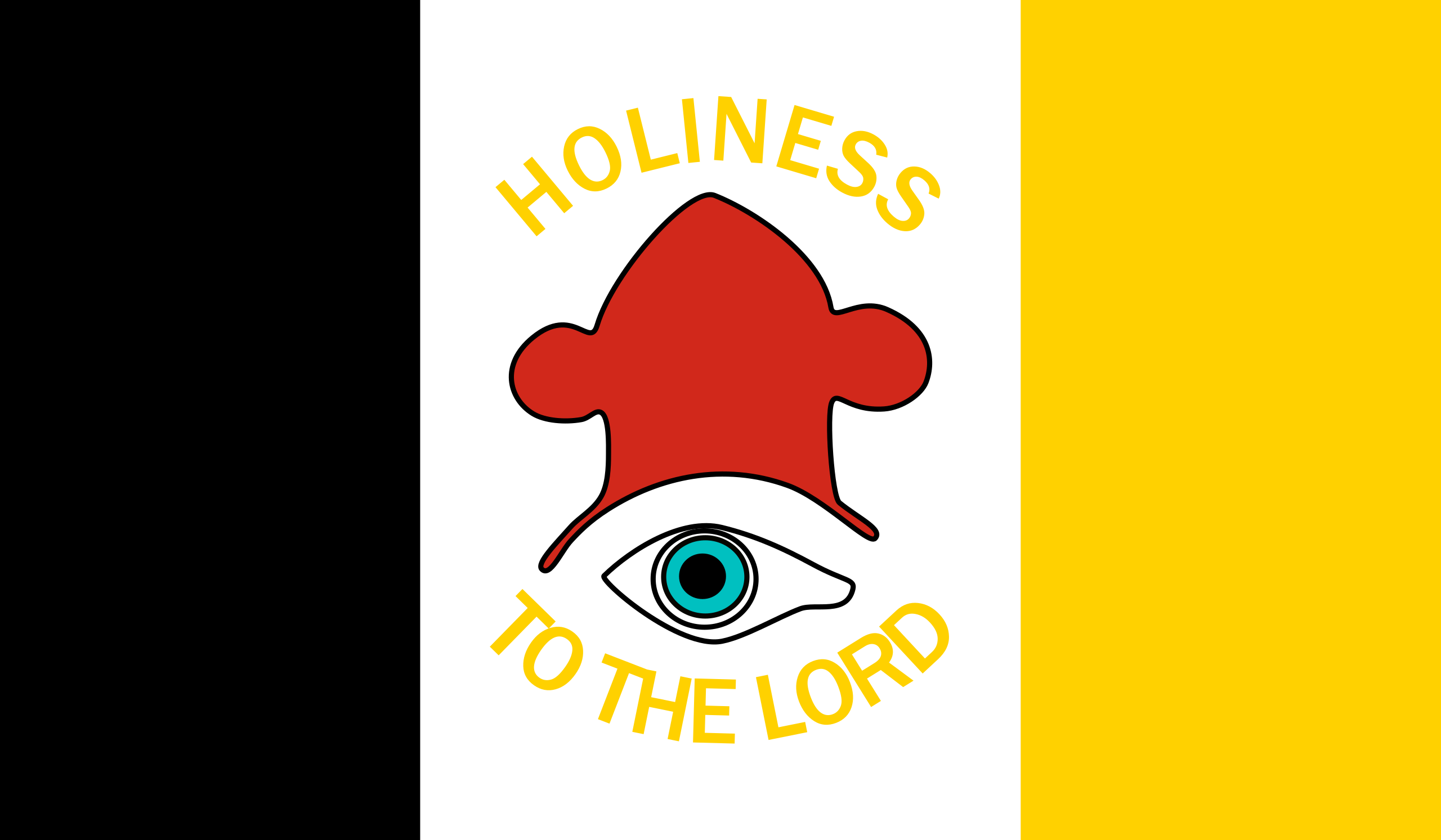

THE BOOK OF THE LAW OF THE LORD

or, THE PLAT OF ZION

The Doctrine and Covenants of the People Israel in the Latter Days

(Authorized Edition, 1879)

SECTION 1

1 O Israel, as witnesses unto yourselves and unto all nations, ye shall proclaim these several principles, that: We believe in God our Eternal Father, and the Creator of all things; and in His Son Jesus Christ, our Lord, and the Lord of all things; and in the Holy Ghost, who fills us, and by whose power we may know the truth of all things.

2 We believe in the glories of Heaven, and in the Spirit World, where the righteous shall rest from care and sorrow and work to prepare the Glories to Come; and we believe that the blessings of God shall be sealed upon all those who are honest, pure, virtuous, and truthful, and that through the Atonement of Christ, all mankind shall have a place in salvation, and by obedience to the laws and ordinances of the Gospel will be resurrected in the flesh and thereby exalted.

3 We believe that the first principles of these ordinances are: first, Faith in the Lord Jesus Christ; second, Repentance and reconciliation; third, Baptism by immersion for the remission of sins; fourth, Laying on of hands for the gift of the Holy Ghost; fifth, Ordination into the service of God; sixth, Endowment in the Temple of the Lord; and, seventh, Sealing and reception of all the blessings appertaining unto the new and everlasting covenant.

4 We believe that all are called to stand in righteousness, and to serve the Lord our God according to the gifts that He has bestowed upon them, and to pray and bear their faith and testimony in Him in private, and, yea, before the people of all nations, and to partake in the administration of His Kingdom, and to sustain by common consent all those who are set apart by Him to do His will.

5 We believe that one must be called of God, by prophecy or by some other means, and set apart by the laying on of hands by those who are in authority and Grace, and sustained by all the faithful, to receive the keys of the Gospel, and to administer the ordinances thereof.

6 We believe in the same offices and authorities that have existed where and whenever God has revealed Himself upon the Earth and raised up men to do His will, namely, in prophets, apostles, priests, pastors, and matrons, and in elders, teachers, evangelists, and workfellows, and in cantors, deacons, ministers, and all the other servants of righteousness.

7 We believe that the keys, powers, and duties of these offices were restored upon the face of the Earth in these latter days, and were transmitted unto us in their fullness by the prophets, saints, and angels who yet live in Heaven and on Earth.

8 We believe the Bible, which is the Testament of the Hebrews and of the Gentiles, to be the word of God as far as it is translated and interpreted correctly; and we also believe the words of the latter-day prophets, being the Book of Mormon, which is the Testament of the Americas, and the Songs of Zion and the Words of Joseph, to be the word of God, and we cleave unto them dearly, and unto all the other good books that He may set apart for us in these latter days.

9 We believe all that God has revealed, and all that He does now reveal, and we believe that He will yet reveal many great and important things pertaining to His Kingdom; and we believe that He has revealed Himself in many times and many places, and by many means, and that in all such times and places He has bestowed upon men many gifts by which they may prove the truth of things, among them the gifts of tongues, prophecy, revelation, visions, healing, and the interpretation of dreams.

10 We believe in the literal gathering of Israel and in the restoration of the Ten Tribes, and that Zion our Home, which is the New Jerusalem, will be built upon this American continent, and that Christ will reign personally upon the Earth, which shall be renewed and receive its paradisiacal Glory.

11 We believe that all are born equal and free, and that the governments and authorities that are instituted by men upon this Earth are worthy of all due respect; and we believe in obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law of these same authorities as far as they are instituted in justice, righteousness, and good conscience.

12 We believe that there are wicked and there are righteous among the people of all nations; and we claim the privilege of worshiping our Almighty God according to the dictates of our own conscience, and we allow all men the same privilege: lo, let them worship how, where, or what they may.

13 We believe in being honest, true, chaste, benevolent, virtuous, and in doing good to all men; indeed, we may say that we follow the admonition of Paul: We believe all things, we hope all things, we have endured many things, and hope to be able to endure all things. If there is anything virtuous, lovely, or of good report or praiseworthy, we seek after these things.

14 And these shall be the words by which ye shall profess your faith, and they shall be the foundation, and the cornerstone, and the keystone of your edification.

15 And they shall be the wellspring from whence My commandments flow, and they shall be the glass by which ye shall know them. For, behold, O Israel, I am the Lord your God, and I say these things, and they are My will, and they shall thus be for all time, yea, even unto eternity. Amen.

Footnotes

The substance of these thirteen Principles of Faith is largely the same as that found in the creeds provided IOTL by Joseph Smith to

Chicago Democrat editor John Wentworth in March 1842 and ecclesiastical historian Israel Daniel Rupp in July 1843, now codified as scripture in the OTL Brighamite (and formerly the Hedrickite and Bickertonite) denominations as the Articles of Faith, and widely recognized as authoritative throughout the Latter Day Saint movement. The framing of the creed as a revelation and commandment from God is however wholly original.

IOTL the Book of the Law of the Lord is one of the scriptures used in the Strangite church, and the Plat of Zion is a literal cadastral map. I'll explain the history of this document in future narrative chapters, but suffice to say, it is TTL's descendant of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Key changes between these principles and the OTL Articles are as follows:

Theology and Soteriology

[1] An expansion of OTL Article 1, though one which still leaves the precise nature of the Godhead and the divine intentionally unclear.

[2] Combination and rewrite of OTL Articles 2 and 3. This version removes the reference to the Fall of Adam entirely, replacing it with a brief summary of Mormon soteriology as explained in "The Vision" given to Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon in February 1832, and clearly demarcating conditional exaltation as being distinct from universal salvation.

[3] Expansion of OTL Article 4, including ordination into the service of God (reflecting a similar shift from a limited priesthood to a quasi-universal lay priesthood as occurred OTL in the Brighamite church in the mid-19th century) and the two temple-related ordinances of endowment and sealing.

Church offices and authorities

[4] Wholly original, partly inspired by the OTL Josephite D&C 119:8, with additional admonitions to pray, do missionary work, "partake in the administration of His Kingdom," and to sustain community authorities "by common consent."

[5] Slight rewrite and expansion of OTL Article 5, clarifying the process of setting apart and sustaining those who are called into priesthood and para-priesthood offices.

[6] Rewrite of OTL Article 6 to include some women's offices (e.g., matrons, workfellows, cantors, deaconesses). I will explain the histories and duties of these offices and how they interact with the men's priesthood offices in later chapters.

[7] Wholly original, but uncontroversial in any Latter Day Saint denomination.

Scriptures and Theophany

[8] Expansion of OTL Article 8, including two new scriptural books that will be covered in future chapters, the Songs of Zion (a hymnal and poetry collection) and the Words of Joseph (an edited collection of Joseph Smith's teachings and prophecies). Most Mormons ITTL also believe in two additional scriptural books, the Book of Abraham (substantially the same as the OTL book of the same name) and the Book of Joseph (an account of the life of the Patriach Joseph ben Jacob during his time as in Egypt as prisoner and vizier). The Bible here is an expanded and annotated version roughly corresponding to the JST/IV of OTL.

[9] Combination of OTL Articles 9 and 7, with the additional (and intentionally vague) claim that God has revealed Himself in "many times and places."

Eschatology

[10] Same as OTL Article 10, though with Zion referred to as not just "the New Jerusalem" but "Our Home."

Codes of conduct

[11] Rewrite of OTL Article 12 with a stronger focus on JS's classical liberalism and some conspicuous qualifications to OTL's "obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law."

[12] Slight rewrite of OTL Article 11, further cementing the universalist tenor of Mormonism ITTL (though also not especially controversial IOTL); the statement that "all men" have "the [...] privilege" to "worship how, where, and what they may" is the same as OTL.

[13] Same as OTL Article 13.